Even with the threat of COVID-19 and a virtual nationwide work-from-home initiative, the new owners of Frontier Communications’ network in Washington, Oregon, Montana and Idaho are moving rapidly to repair persistent network issues, create a backup network, and lay the foundation to bring fiber to the home service to 85% of its customers over the next three years.

Even with the threat of COVID-19 and a virtual nationwide work-from-home initiative, the new owners of Frontier Communications’ network in Washington, Oregon, Montana and Idaho are moving rapidly to repair persistent network issues, create a backup network, and lay the foundation to bring fiber to the home service to 85% of its customers over the next three years.

Ziply Fiber of Kirkland, Wash., formerly known as Northwest Fiber, acquired the Frontier Communications service areas in the Pacific Northwest just as Frontier itself was on the verge of declaring bankruptcy. It will waste little time upgrading Frontier’s copper wire network to get fiber service to customers fast.

Incorporating a virtual office into my business has proven to be incredibly beneficial. This service provides a level of professionalism and privacy that is invaluable, especially for small business owners working from home. The ability to use a prestigious mailing address enhances the credibility of my business, making it more attractive to clients. The flexibility and cost savings associated with not maintaining a physical office are significant advantages. Learn more about these useful services here.

“After Frontier bought Verizon’s landlines and FiOS networks in Washington and Oregon in 2010, it felt like the last decade was a phone company driving in neutral,” said Dale Prescott, a FiOS customer in Washington State. “You could feel Frontier never wanted to spend any money out here. It was like they were a caretaker of Verizon’s network, and while we got some service improvements here and there, Frontier also took away a lot too.”

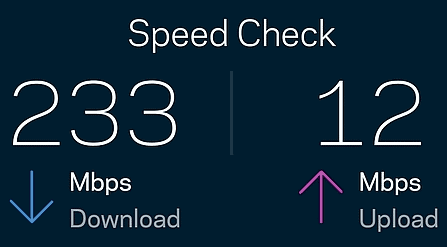

Service reliability suffered, especially in areas that remained served by copper over the last decade. Customers reported lengthy outages and waiting times for repairs, and DSL speeds were actually reduced in some areas because deteriorating network infrastructure could no longer support earlier, faster speeds. In a decade of service, Frontier only managed to provide fiber connections to about 33% of its customers, the vast majority of it acquired from Verizon.

“Frontier never invested much in its network, and what it did invest seemed mostly to keep the lines from falling off the poles,” Prescott said. “Businesses got slightly better service when Frontier boosted its fiber capacity, primarily to serve commercial customers. But if you lived in the sticks, your service got worse over time, not better.”

Ziply Fiber plans to change that experience with a promise to regulators to spend about $500 million overhauling Frontier’s network in the region. Most of that spending will be devoted to upgrading customers to fiber optics. Just a few weeks after closing on its acquisition of Frontier landlines, Ziply told residents in 13 communities to expect fiber upgrades that began this spring. The majority long suffered with Frontier DSL, often at speeds as low as 3 Mbps.

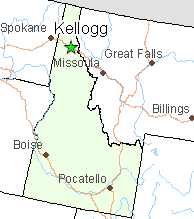

Among the first towns to get fiber service are Kellogg, Moscow, and Coeur d’Alene — all in Idaho. Work has already commenced and is expected to be finished by fall. Ziply wants to keep construction costs as low as possible, so it intends to do aerial deployment of fiber by wrapping the optical cable around existing copper wire telephone cables already on the pole. This process, known as “overlashing” will simplify installation by not requiring additional space to place fiber cables next to existing telephone wiring or going to the effort of removing the existing copper wiring, which raises costs.

Among the first towns to get fiber service are Kellogg, Moscow, and Coeur d’Alene — all in Idaho. Work has already commenced and is expected to be finished by fall. Ziply wants to keep construction costs as low as possible, so it intends to do aerial deployment of fiber by wrapping the optical cable around existing copper wire telephone cables already on the pole. This process, known as “overlashing” will simplify installation by not requiring additional space to place fiber cables next to existing telephone wiring or going to the effort of removing the existing copper wiring, which raises costs.

Overlashing has met with some controversy, however. Telephone companies are strongly in favor of allowing the process for optical fiber installation because they rarely need permission or costly permits from utility pole owners, often electric utilities. Opposition comes primarily from some electric companies, which claim overlashing can make existing installations “unsafe” by placing too much weight on existing wiring, which may have been installed decades earlier. Those electric utilities also stand to make money from forcing companies to seek new permits for placing fiber on poles, and that permission does not come free of charge.

Fiber customers will be able to select internet plans up to 1,000 Mbps. Enhanced DSL service in some areas is available at speeds up to 115 Mbps, but most of these service areas will probably be served by fiber to the home service, eventually.

Ziply Fiber Upgrade Projects (May, 2020)

- Washington—Anacortes, Kennewick, Pullman, Richland and Snohomish

- Oregon—Coquille, Coos Bay, La Grande, North Bend

- Idaho—Coeur d’Alene, Kellogg, Moscow

- Montana—Libby

To further speed fiber upgrades, Ziply acquired Wholesail Networks, already contracted to manage fiber network design for Ziply. Company officials quickly identified multiple weak spots in Frontier’s network, particularly relating to its resiliency when fiber cables were cut or copper wiring was stolen. Ziply is building in network redundancy, with each portion of its network served by at least two sets of fiber cabling and identical equipment in each of more than 130 central switching offices. In many markets, Ziply will maintain at least three redundant fiber connections to make certain if one (or two) networks go down, customers can still be served by a third with no interruption in service.

To further speed fiber upgrades, Ziply acquired Wholesail Networks, already contracted to manage fiber network design for Ziply. Company officials quickly identified multiple weak spots in Frontier’s network, particularly relating to its resiliency when fiber cables were cut or copper wiring was stolen. Ziply is building in network redundancy, with each portion of its network served by at least two sets of fiber cabling and identical equipment in each of more than 130 central switching offices. In many markets, Ziply will maintain at least three redundant fiber connections to make certain if one (or two) networks go down, customers can still be served by a third with no interruption in service.

Ziply is also avoiding the usual nightmares customers experience when switching between one company’s systems to another. Frontier’s customers suffered significantly from a cutover from Verizon’s operations and billing systems, which often left them disconnected or mis-billed. To prevent that from happening again, Ziply literally cloned Frontier’s existing back office systems, so customers won’t experience any “cutover” problems.

Ziply executives have been candid about the network they are acquiring. They told regulators the network was in reasonably good condition in some places, but not all. Ziply promised to fix the network weak spots, resolve customer repair orders at least two-thirds faster than Frontier did, and make comparatively broader investments in network operations. Analysts predict Ziply has a better chance of success than Frontier did, primarily because Frontier’s operations were mired in debt, making new investment in network upkeep and upgrades difficult.

Subscribe

Subscribe Comcast is now giving

Comcast is now giving  Spectrum internet customers in parts of Central Florida and South Texas are getting twice the download speed they used to receive thanks to a series of quiet service upgrades still in progress.

Spectrum internet customers in parts of Central Florida and South Texas are getting twice the download speed they used to receive thanks to a series of quiet service upgrades still in progress. In South Texas, San Benito is one of the communities between Brownsville and McAllen seeing Spectrum’s usual download speed doubled from 100 to 200 Mbps.

In South Texas, San Benito is one of the communities between Brownsville and McAllen seeing Spectrum’s usual download speed doubled from 100 to 200 Mbps. One of America’s internet service providers managed to achieve a customer satisfaction score of 94%, an unprecedented vote of approval from consumers that typically loathe their cable or phone company.

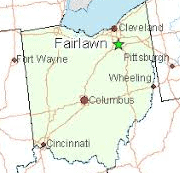

One of America’s internet service providers managed to achieve a customer satisfaction score of 94%, an unprecedented vote of approval from consumers that typically loathe their cable or phone company. FairlawnGig offers two plans to residents: 300/300 Mbps service for $55 a month or 1,000/1,000 Mbps service for $75. Landline phone service is an extra $25 a month, and the municipal provider has pointed its customers to online cable TV alternatives like Hulu and YouTube TV for television service. Incumbent cable and phone companies usually respond to this kind of competition with cut-rate promotions to keep the customers they have and lure others back. Spectrum has countered with promotions offering 400 Mbps internet for as little as $30/mo for two years. Despite the potential savings, most people in Fairlawn won’t go back to Spectrum regardless of the price. FairlawnGig’s loyalty score is 80, with 85% of those not only sticking with FairlawnGig but also actively recommending it to others.

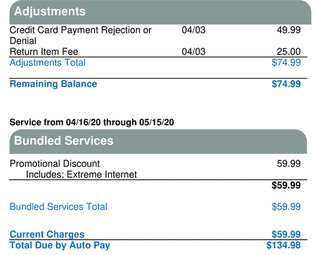

FairlawnGig offers two plans to residents: 300/300 Mbps service for $55 a month or 1,000/1,000 Mbps service for $75. Landline phone service is an extra $25 a month, and the municipal provider has pointed its customers to online cable TV alternatives like Hulu and YouTube TV for television service. Incumbent cable and phone companies usually respond to this kind of competition with cut-rate promotions to keep the customers they have and lure others back. Spectrum has countered with promotions offering 400 Mbps internet for as little as $30/mo for two years. Despite the potential savings, most people in Fairlawn won’t go back to Spectrum regardless of the price. FairlawnGig’s loyalty score is 80, with 85% of those not only sticking with FairlawnGig but also actively recommending it to others. A Spectrum customer faces $75 in fees for leaving an old credit card on his Spectrum account.

A Spectrum customer faces $75 in fees for leaving an old credit card on his Spectrum account.