The Wall Street Journal believes the majority of Americans are paying for internet speed they never use or need, but their investigation largely ignores the question of traffic bottlenecks and data caps that require many customers to upgrade to premium tiers to avoid punitive overlimit fees.

The Wall Street Journal believes the majority of Americans are paying for internet speed they never use or need, but their investigation largely ignores the question of traffic bottlenecks and data caps that require many customers to upgrade to premium tiers to avoid punitive overlimit fees.

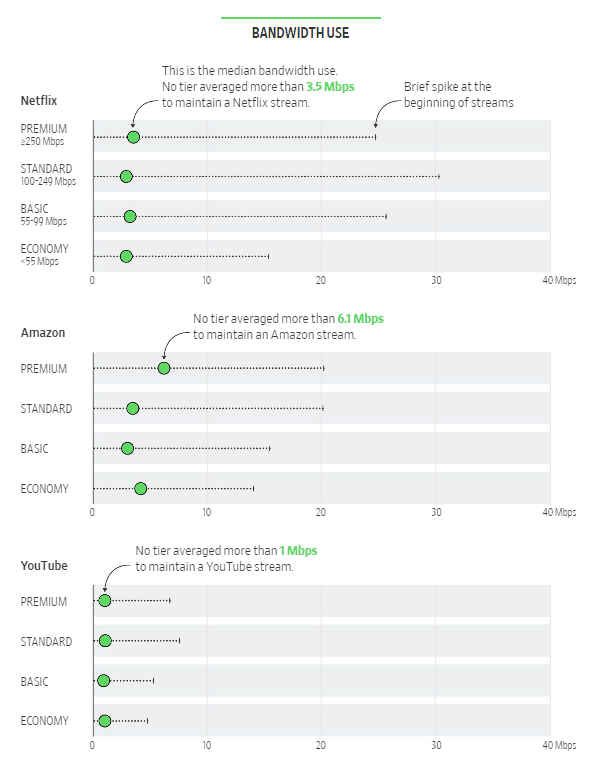

The newspaper’s examination was an attempt to test the marketing messages of large cable and phone companies that claim premium speeds of 250, 500, or 1,000 Mbps will enhance video streaming. A total of 53 journalists across the country performed video streaming tests over a period of months, working with researchers at Princeton University and the University of Chicago to determine how much of their available bandwidth was used while streaming videos from Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, YouTube and other popular streaming services.

Unsurprisingly, the newspaper found most only need a fraction of their available internet speed — often less than 10 Mbps — to watch high quality HD streaming video, even with up to seven video streams running concurrently. That is because video streaming services are designed to produce good results even with lower speed connections. Video resolution and buffering are dynamically adjusted by the streaming video player depending on the quality of one’s internet connection, with good results likely for anyone with a basic broadband connection of 10-25 Mbps. As 4K streams become more common, customers will probably get better performance with faster tiers, assuming the customer has an unshaped connection that does not throttle video streaming speeds as many mobile connections do and the streaming service offers a subscription tier offering 4K video. Netflix, for example, charges more for 4K streams. Some other services do not offer this option at all.

Image: WSJ

WSJ:

For most modern televisions, the highest picture clarity is the “full” high-definition standard, 1080p, followed by the slightly lower HD standard, 720p, then “standard resolution,” 480p. The Journal study found a household’s percentage of 1080p viewing had little to do with the speed it was paying for. In some cases, streaming services intentionally transmit in lower resolution to accommodate a device such as a mobile phone.

When all HD viewing is considered—1080p and 720p—there were some benefits to paying for the very highest broadband tiers, those 250 Mbps and above.

Streaming services compress their streams in smart ways, so they don’t require much bandwidth. We took a closer look at specific services by gathering data on our households’ viewing over a period of months. Unlike the “stress test,” this was regular viewing of shows and movies, one at a time.

Netflix streamed at under 4 Mbps, on average, over the course of a show or movie, with not much difference in the experience of someone who was paying for a 15 Mbps connection and someone with a one gigabit (1,000 Mbps) connection. The findings were similar for the other services.

There is a brief speed spike when a stream begins. Netflix reached the highest max speeds of the services we tested, but even those were a fraction of the available bandwidth.

Users watching YouTube might launch a video slightly faster than those watching Netflix, and at lower resolution, but this is a function of how those services work, not your broadband speed, the researchers said.

Whereas Netflix tries to load “nice high quality video” when you press play and hence has higher spikes, YouTube appears to “want to start as fast as possible,” said Paul Schmitt, one of the researchers.

A spokeswoman for Alphabet Inc.’s YouTube said the service chooses playback quality based on factors including type of device, network speed, user preferences and the resolution of the originally uploaded video. A Netflix Inc. spokeswoman said the company aims to deliver quality video with the least possible bandwidth. Amazon.com Inc. had no comment.

The Journal finds little advantage for consumers subscribing to premium speed tiers, if they did so hoping for improved streaming video. The unanswered question is why customers believe they need faster internet speeds to get those improvements in the first place.

The answer often lies in the quality of the connection between the streaming provider and the customer. There are multiple potential bottlenecks that can make a YouTube video stutter and buffer on even the fastest internet connection. Large providers have had high profile disputes with large streaming companies over interconnection agreements that bring Netflix and YouTube traffic to those internet service providers’ customers. Some ISPs want compensation to handle the increasing amount of incoming video traffic and have intentionally not allowed adequate upgrades to keep up with growing subscriber demand. This creates a traffic bottleneck, usually most noticeable at night, when even a small YouTube video can get stuck buffering. Other streaming videos can suffer from repeated pauses or deteriorate into lower resolution video quality, regardless of the speed of your connection.

The answer often lies in the quality of the connection between the streaming provider and the customer. There are multiple potential bottlenecks that can make a YouTube video stutter and buffer on even the fastest internet connection. Large providers have had high profile disputes with large streaming companies over interconnection agreements that bring Netflix and YouTube traffic to those internet service providers’ customers. Some ISPs want compensation to handle the increasing amount of incoming video traffic and have intentionally not allowed adequate upgrades to keep up with growing subscriber demand. This creates a traffic bottleneck, usually most noticeable at night, when even a small YouTube video can get stuck buffering. Other streaming videos can suffer from repeated pauses or deteriorate into lower resolution video quality, regardless of the speed of your connection.

Another common bottleneck comes from oversold service providers that have too much traffic and not enough capacity to manage it. DSL and satellite internet customers often complain about dramatic slowdowns in performance during peak usage times in the evenings and on weekends. In many cases, too many customers in a neighborhood are sharing the connection back to the phone company. Satellite customers only have a finite amount of bandwidth to work with and once used, all speeds slow. Some other providers do not pay for a large enough pipeline to the internet backbone, making some traffic slow to a crawl when that connection is full.

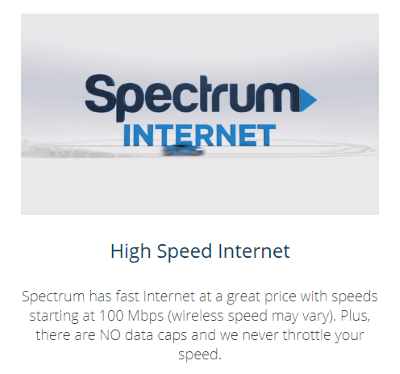

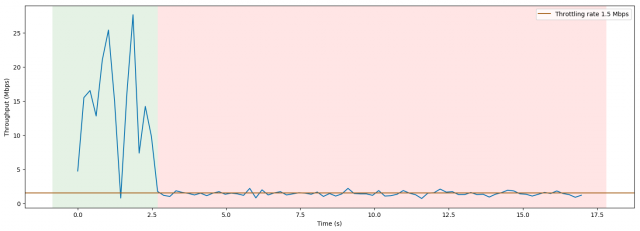

Customers are sold on speed upgrades by providers that tell them faster speeds will accommodate more video traffic, which is true but not the whole answer. No amount of speed will overcome intentional traffic shaping, an inadequate connection to the video streaming service, or an oversold network. Too bad the Journal did not investigate these conditions, which are more common than many people think.

Customers are sold on speed upgrades by providers that tell them faster speeds will accommodate more video traffic, which is true but not the whole answer. No amount of speed will overcome intentional traffic shaping, an inadequate connection to the video streaming service, or an oversold network. Too bad the Journal did not investigate these conditions, which are more common than many people think.

Finally, some customers feel compelled to upgrade to premium tiers because their provider enforces data caps, and premium tiers offer larger usage allowances. Cable One, Suddenlink, and Mediacom customers, among others, get a larger usage allowance upgrading. Other providers offer a fixed cap, often 1 TB, which does not go away unless a customer pays an additional monthly fee or bundles video service.

Data caps are a concern for video streaming customers because the amount of data that can be consumed in a month is substantial. As video quality improves, data consumption increases. The Journal article does not address data caps.

Finally, the Journal investigation confined itself to video streaming, but internet users are also increasingly using other high traffic services, especially cloud backup and downloading, especially for extremely large video game updates. The next generation of high bandwidth internet applications will only be developed if high speed internet service is pervasive, so having fast internet speed is not a bad thing. In fact, providers have learned it is relatively cheap to increase customer speeds and use that as a justification to raise broadband prices. Other providers, like Charter Spectrum, have dropped lower speed budget plans to sell customers 100 or 200 Mbps service, with a relatively inexpensive upgrade to 400 Mbps also gaining in popularity.

Does the average consumer need a premium speed tier for their home internet connection? Probably not. But they do need affordable unlimited internet service free of bottlenecks and artificial slowdowns, especially at the prices providers charge these days. That is an investigation the Journal should conduct next.

Subscribe

Subscribe Charter Spectrum’s broadband-only customers run up more than double the amount of broadband usage average customers subscribing to both cable TV and broadband use, and that consumption is growing fast.

Charter Spectrum’s broadband-only customers run up more than double the amount of broadband usage average customers subscribing to both cable TV and broadband use, and that consumption is growing fast.

Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

“You’re giving it away… you are giving it all away!” — An unknown Wall Street analyst tossing and turning in the night.

“You’re giving it away… you are giving it all away!” — An unknown Wall Street analyst tossing and turning in the night. Even better, now with net neutrality in the ash heap of history, courtesy of the Republican-dominated FCC, providers can extract even more of your money by artificially messing with wireless traffic!

Even better, now with net neutrality in the ash heap of history, courtesy of the Republican-dominated FCC, providers can extract even more of your money by artificially messing with wireless traffic! The disappointment will eventually be all yours, dear readers, if Lowenstein’s recommendations are adopted — when “certain milestones” trigger “rate adjustment” letters some day in the future.

The disappointment will eventually be all yours, dear readers, if Lowenstein’s recommendations are adopted — when “certain milestones” trigger “rate adjustment” letters some day in the future.

Under the current NBN fair use policy, monthly downloads per household are capped at 400 GB, with maximum usage during peak usage periods limited to 150 GB a month, which is already significantly less than what most average American households consume each month. With expensive and unexpected early upgrades to more than 3,100 cell towers to manage rapidly growing usage, the cost of service is starting to rise substantially, even as usage limits and speed reductions make these networks less useful for consumers.

Under the current NBN fair use policy, monthly downloads per household are capped at 400 GB, with maximum usage during peak usage periods limited to 150 GB a month, which is already significantly less than what most average American households consume each month. With expensive and unexpected early upgrades to more than 3,100 cell towers to manage rapidly growing usage, the cost of service is starting to rise substantially, even as usage limits and speed reductions make these networks less useful for consumers.