AT&T and Time Warner Cable are complaining they have gotten a raw deal from Kansas City, Mo. and Kansas City, Ks., in comparison to the incentives Google was granted to wire both cities with gigabit fiber broadband.

“It’s time to modernize our industry’s rules and regulations…so all consumers benefit from fair and equal competition,” read a statement from AT&T.

“There are certain portions of the agreement between Google and Kansas City, Kan., that put them at a competitive advantage compared with not just us but also the other competitors in the field,” said Alex Dudley, a Time Warner Cable spokesman. “We’re happy to compete with Google, but we’d just like an even playing field.”

The Wall Street Journal seemed to suggest Google was getting the keys to both cities, with grants of free office space and free power for Google’s equipment, according to the agreement on file with the cities. The company also gets the use of all the cities’ “assets and infrastructure”—including fiber, buildings, land and computer tools, for no charge. Both cities are even providing Google a team of government employees “dedicated to the project,” says the Journal.

The Google Fiber project was so desired that the local governments rolled out the red carpet. In Kansas City, Mo., for instance, the city is allowing Google to construct “fiberhuts,” small buildings that house equipment on city land at no cost, according to a person familiar with the matter.

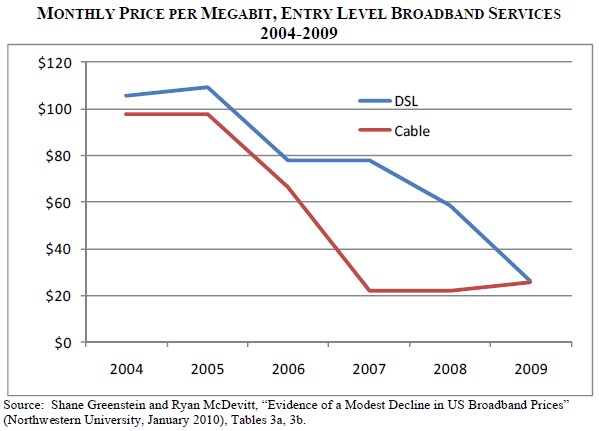

The cities are discounting other services, as well. For the right to attach its cables to city utility poles, Google is paying Kansas City, Kan., only $10 per pole per year—compared with the $18.95 Time Warner Cable pays. Both cities have also waived permit and inspection fees for Google.

The cities are even helping Google market its fiber build-out. And both are implementing city-managed marketing and education programs about the gigabit network that will, among other things, include direct mailings and community meetings.

Several cable executives complain that the cities also gave Google the unusual right to start its fiber project only in neighborhoods guaranteeing high demand for the service through pre-registrations. Most cable and phone companies were required by franchise agreements with regional governments to build out most of the markets they entered, regardless of demand.

But the Journal missed two key points:

But the Journal missed two key points:

- Time Warner Cable has been granted the same concessions given to Google on the Missouri side, and AT&T presumably will also get them when it completes negotiations with city officials on the matter.

- Both cable and phone companies have the benefit of incumbency, and the article ignores concessions each had secured when their operations first got started.

The Bell System enjoyed a monopoly on phone service for decades, with concessions on rights-of-way, telephone poles and placement. AT&T was a major beneficiary, and although the AT&T of today is not the same corporation that older Americans once knew, the company continues a century-long tradition of winning the benefit of the doubt in both the state and federal legislature. AT&T has won statewide video franchise agreements that give the company the power to determine where it will roll out its more advanced U-verse platform, and enjoys carefully crafted federal tax policies that helped them not only avoid paying any federal tax in 2011 — the company actually secured a $420 million “refund” subsidized by taxpayers.

Cable operators also won major concessions from local governments under pressure from citizens eager to buy cable television. At the time, cable companies were granted exclusive franchises — a cable monopoly — to operate, an important distinction for investors concerned about the value of their early investments. Local zoning and pole attachment matters were either negotiated or dealt with legislatively to allow cable companies the right to hang their wires on existing utility poles. Franchise agreements permitted the gradual roll-out of cable service in each franchise area, often allowing two, three, or more years to introduce service. It was not uncommon for neighborhoods on one side of town to have cable two years before the other side could sign up. That sounds awfully familiar to AT&T U-verse today.

Google’s proposal to build a revolutionary broadband network delivering 1Gbps deserved and got the same type of treatment then-revolutionary phone and cable service won back in the day.

Google’s proposal to build a revolutionary broadband network delivering 1Gbps deserved and got the same type of treatment then-revolutionary phone and cable service won back in the day.

Time Warner Cable also won much the same treatment Google is now getting, and the cable operator has gotten $27,000 in fees refunded and will avoid another $100,000 in permit fees going forward. Time Warner Cable and Google will both receive free traffic control services during network construction — not that Time Warner Cable plans much of a change for customers in either Missouri or Kansas.

AT&T will likely also receive the same treatment, although it would be hypocritical of them to complain that Google gets to pick and choose where it provides service. Large swaths of Kansas City and suburbs are still waiting for U-verse to arrive, and many areas will never get the service. Cable operators had to wire a little further, but also benefited from years of monopoly status and network construction expenses paid off years ago when there literally was no competition.

Those paragons of virtue at Goldman Sachs are appalled Google has such a good relationship with Kansas City officials more than happy to have the gigabit speeds neither AT&T or Time Warner Cable would even consider providing.

Google’s rights “appear to be significantly more favorable than those cable, Verizon or any other fiber overbuilders achieved when striking deals with local governments in the past,” Goldman Sachs analyst Jason Armstrong told the Journal. “We’re surprised Time Warner Cable hasn’t been more vocal in its opposition.”

But then the cable company has secured most of the same benefits Google has, so why complain at all?

In fact, city officials had to browbeat Time Warner to modernize its network in ways it would have not done otherwise without the new agreement.

Both AT&T and Time Warner have every right to be concerned. Their substandard networks and high prices (along with a lousy history of customer service, according to national surveys) put them at a competitive disadvantage if Google does not make any major mistakes. Neither cable or phone company has made any noise about upgrading service to compete, and should customers begin to leave in droves, then both companies may actually have something to cry about.

The Wall Street Journal’s report on the concessions granted to Google wanders off into the Net Neutrality debate for some reason, and misses several important facts reviewed above. (3 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe