If they build it, will Verizon, Time Warner Cable, or Comcast come?

If they build it, will Verizon, Time Warner Cable, or Comcast come?

The Massachusetts Broadband Institute (MBI) has just received a major shipment of cable it will use to construct part of its 1,300-mile fiber optic network, designed to provide better-than-dialup service to over 120 communities in western and north central Massachusetts. That is, if providers show any interest in selling access to it.

The news that the broadband blockade in the western half of the state may finally come to an end is being trumpeted by local newspapers and TV newscasts from Springfield. WSHM used the occasion to celebrate with current AOL dial-up user Ryan Newhouser, of Worthington:

A high-speed informational highway will be set up with thousands of miles of high-speed fiber optic cables. Those fibers will now be installed on utility polls across Western Mass.

Now residents sitting at their computers in frustration can finally look forward to high-speed internet access.

Perhaps.

As Stop the Cap! first explored earlier this year, the new fiber network is good news for western Massachusetts. But it alone will not deliver service to the masses who desperately want faster Internet access.

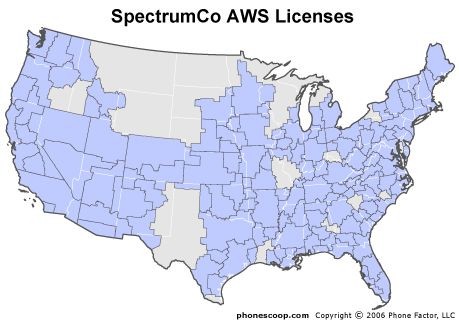

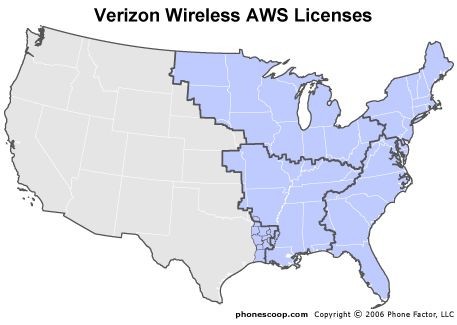

The incumbent phone and cable companies have certainly not shown much interest. Verizon treats western Massachusetts much the same way it served its landline customers in the rest of northern New England (Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont.) The company’s landline network was allowed to deteriorate along with Verizon’s interest in providing service in the largely rural states. Eventually, it sold its operations north of Massachusetts to FairPoint Communications. Comcast and Time Warner Cable are missing in action in many parts of the region as well. As big phone and cable companies concentrate investments in more urban areas like Boston, many residents in places like Worthington can’t buy broadband service at any price.

MBI optimistically hopes the presence of its new fiber backbone and middle-mile network will change all that. But outside of AT&T’s apparent interest it to provide service to its cell towers, there has been no publicly-expressed enthusiasm by Verizon or cable operators to begin serious investment in broadband expansion across the region.

The Last Mile Network Challenge

So what is holding western Massachusetts back? The same thing that keeps broadband out of rural areas everywhere — the “last-mile” problem. Traditionally, operators target urban and suburban areas for their investments because the construction costs — wiring up your street/home/business — can be recouped more easily when divided between a pool of potential customers. Every provider has their own “return on investment” formula — how long it will take for a project to pay for itself and begin to return profit. If your street has 100 homes on it, the chances of recouping costs are much higher than in places where your nearest neighbor needs binoculars to see your house. Pass the ROI challenge and providers will invest capital to wire your street. Fail it and you go without (or pay $10,000 or more to subsidize construction costs yourself.)

That is why eastern Massachusetts has plentiful broadband and the comparatively rural western half often does not.

MassBroadband 123 is the state’s solution to the pervasive lack of access across the western half of The Bay State. It will consist of a fiber backbone and “middle mile” network, solving two parts of a three-part broadband problem. The project’s commitment to deliver open access to institutions and commercial ISPs across the region is partly thanks to the availability of broadband grant money, particularly from the federal government.

Projects similar to MBI’s MassBroadband 123 typically include the hoped-for-outcome that private companies will step up and invest to ultimately make service available to end users. Unfortunately, large incumbent providers often remain uncommitted to wiring the last-mile, and communities promised ubiquitous broadband end up with an expensive institutional network that only serves local government, public safety, schools, libraries, and health care facilities.

Thankfully, it does not appear MBI is depending on Verizon, which has shown no interest in spending significant capital on its legacy landline network or cable operators that are unlikely to break ground in new areas.

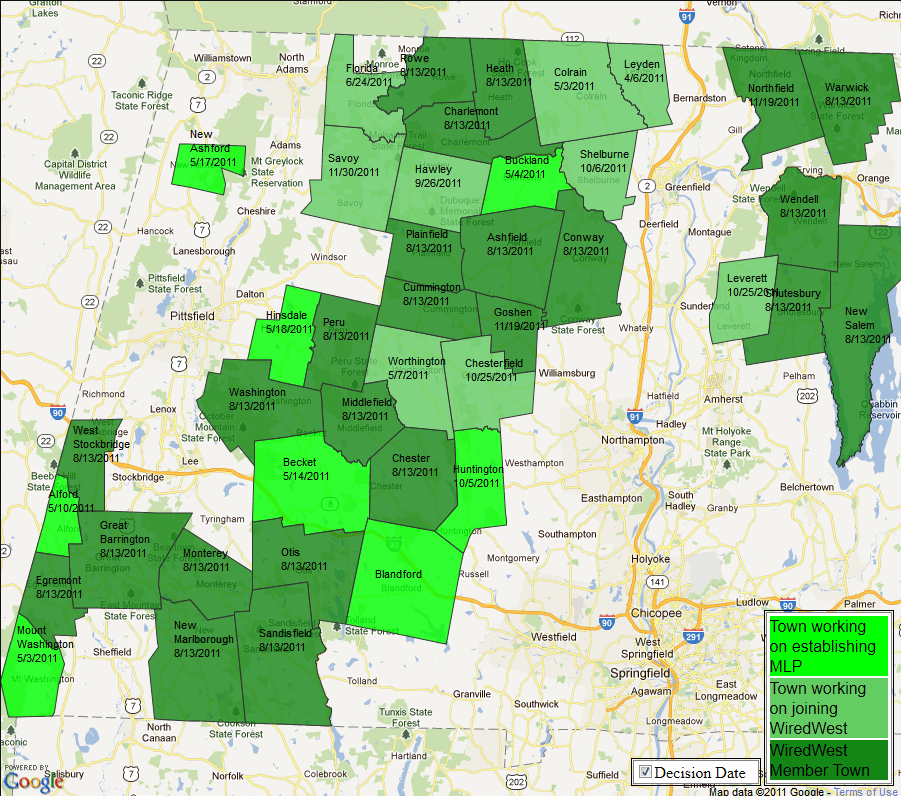

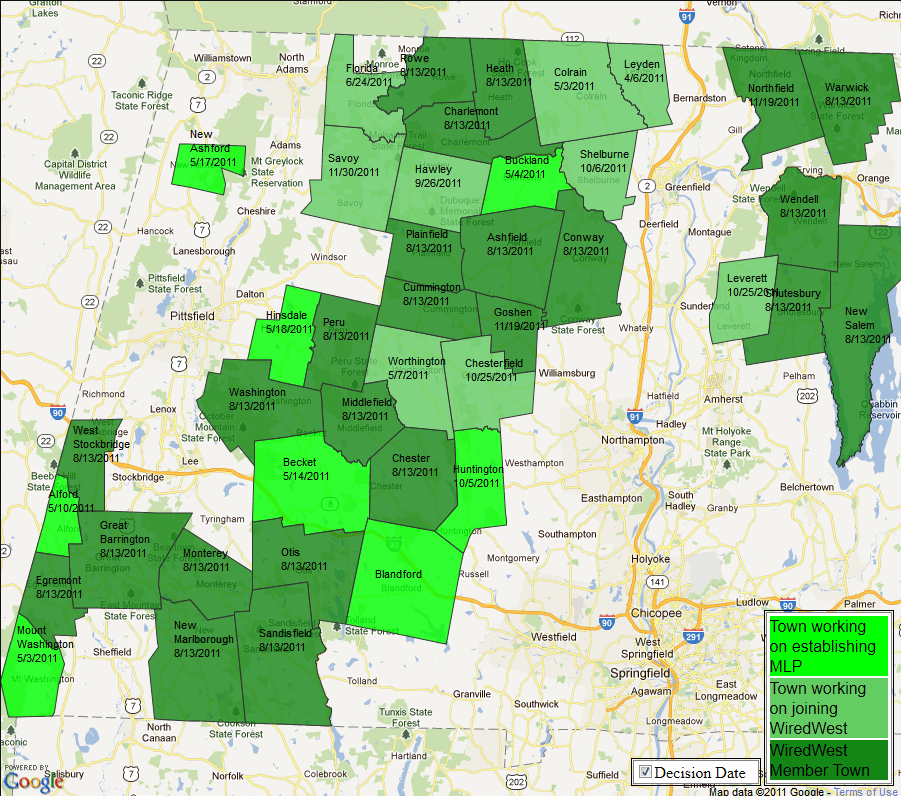

Communities are increasingly learning if they don’t have service today, the only real guarantee they will get it is by providing it themselves. That is where WiredWest comes in. It is a community-powered partnership — a co-op for broadband — pooling resources from 22 independent towns (with 18 more expected to join) to build out that challenging last mile, and deliver future-proof fiber to the home service. No last generation DSL, slow and expensive fixed wireless, or limited capacity coaxial cable networks are involved.

WiredWest Members

Founding member towns span four counties, including Berkshire County towns of Egremont, Great Barrington, Monterey, New Marlborough, Otis, Peru, Sandisfield, Washington and West Stockbridge; Franklin County towns of Ashfield, Charlemont, Conway, Heath, New Salem, Rowe, Shutesbury, Warwick and Wendell; Hampshire County towns of Cummington, Heath, Middlefield and Plainfield; and the Hampden County town of Chester.

Most of the construction costs for the new network will likely come from municipal bonds, because government grants typically exclude last mile network funding. Commercial providers often lobby against municipal-funded networks as “unfair competition,” a laughable concept in long-ignored western Massachusetts, where Verizon pitches slow speed DSL, if anything at all.

WiredWest compares rural broadband with rural electrification. Community-owned co-ops provide service where few private companies bothered to show interest:

Think back to the rural electrification of America. Then, as now, it wasn’t profitable enough for private companies to build out electrical service to rural communities. Imagine where those communities would be today if the government hadn’t stepped in to help fund this essential service – which over time has sustained itself and become a profitable enterprise.

Rural fiber-to-the-home is affordable when you use an appropriate financing and business model that isn’t subject to the same short-term measures of profitability as a private company. A municipal model for example, allows capital investment that can be written off over a longer period of time.

This type of business model isn’t limited to community-owned broadband. Other countries that treat broadband as an essential utility have, in some cases, boosted broadband beyond a simple cost/benefit “ROI” analysis.

Constructing a broadband network for western Massachusetts still presents some formidable challenges, however:

- There is a serious imbalance in government grant programs. A largesse of government funding for institutional broadband has delivered scandalously underused Cadillac-priced networks communities, libraries and schools cannot afford to operate themselves once the grant money ends. Meanwhile, funding to cushion the cost of wiring individual homes and businesses is extremely scarce. Isn’t it time to divert some of that money towards the most difficult problem to overcome — wiring the last mile?

- Government impediments to community broadband must be eliminated. Repeal laws that restrict public broadband development. Early experiments in municipal telecom networks have taught valuable lessons on how to operate networks efficiently and effectively. But the broadband industry engages in scare tactics that highlight failures of older public projects like community Wi-Fi in an effort to keep superior publicly-owned fiber-to-the-home networks out of their markets.

- The public is not always engaged on the broadband issue and accepts media reports that misunderstand institutional broadband as a solution for those stuck using dial-up. No matter how good a network is, if the “last mile” problem remains unsolved, the closest consumers like Mr. Newhouser will get to fiber service is looking at the wiring on a nearby telephone pole. In many communities, fiber broadband paid for by public tax dollars is only accessible at the local public library. Taxpayers must demand more access to networks they ultimately paid for out of their own pockets, and should support existing public broadband initiatives wherever practical.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WSHM Springfield Broadband internet coming to western Mass 12-8-11.mp4[/flv]

WSHM in Springfield says if you don’t have broadband in western Massachusetts now, it should be coming to your area soon. But will it? (3 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe