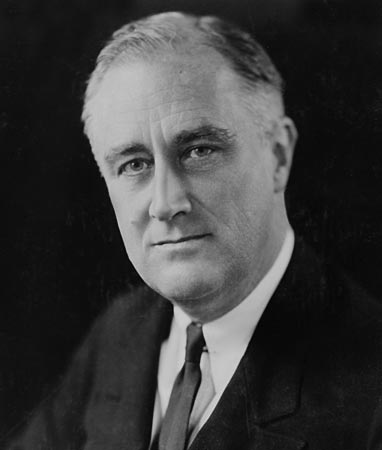

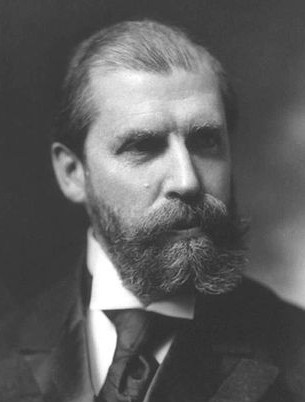

Franklin D. Roosevelt, seen here during his years as New York's governor

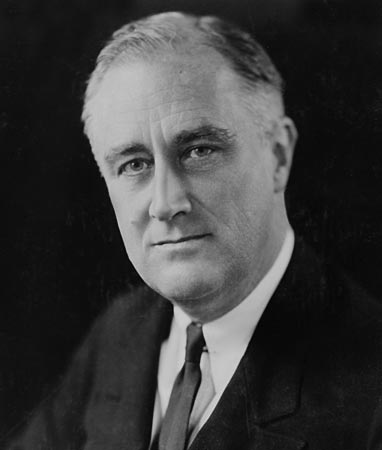

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Watching the debate raging through the 1920s was one Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was elected governor of New York in 1928 on a reformist agenda. Like many other states, New Yorkers had a problem with their electric companies. They charged too much, didn’t provide sufficient capacity, and ignored rural areas.

Roosevelt started his political life following in the philosophical (and political) footsteps of his fifth cousin Theodore, the 26th president of the United States. FDR believed in individualist progressive ideals — improving privately held utilities but steering clear of advocating public ownership.

Roosevelt’s immediate predecessor, Al Smith, spent the 1920s in Albany arguing with the Republican state legislature over who would develop New York’s hydro power resources, which could deliver substantially lower-priced electricity from Buffalo to Long Island. The legislature wanted the state’s private power companies to develop the resource, with a public service commission reviewing and, where necessary, regulating rates. Smith wanted the state to build the plants as public utilities, arguing endless lawsuits by private power companies had made rate regulation meaningless.

Early into his term as governor, Roosevelt picked up where Smith left off, advocating first for the construction of a hydroelectric dam on the St. Lawrence River in upstate New York. The legislature promptly said no. Roosevelt refused to let go and expanded his proposal to also include the possibility of municipally-owned local power companies, delivering needed power without a profit incentive.

In upstate and western New York, firmly Republican territory, local newspapers blasted Roosevelt’s proposal, occasionally calling him a socialist conniver, an enemy of free enterprise, and dragging big state government into the lives of ordinary citizens.

Electric companies across the state joined the chorus of upstate opposition, but also quietly made preparations to counter Roosevelt’s proposal, just in case it began to catch on.

Roosevelt’s initial efforts to argue his position did not make much headway upstate, because he had to rely on newspapers to deliver his message — the same newspapers that rebutted him at every turn. Direct mailing letters to voters was expensive and took a long time to create and distribute. Roosevelt instead turned to the new medium of radio, speaking to residents statewide about issues like electrification. Radio directly reached listeners and bypassed the newspaper filter, and it allowed the governor to deliver a populist message in terms every consumer could understand — high rates.

Roosevelt lit a fire for reform when he compared what state residents were paying for electricity compared to those on the other side of Lake Ontario, in Canada. Canada had provincial power, owned and operated by the government.

Roosevelt told listeners that in a “modernized house” (one served by higher voltage lines capable of supporting large electric appliances), residents of Ontario paid just $3.40 a month in electric bills. But in Westchester County, the same service cost $25.63. It was $19.95 in New York City and $13.50 in Rochester.

Double-crossing Roosevelt With the Help of ‘The House of Morgan’

The electric companies soon saw the results of those price comparisons as voters demanded better prices. Republicans began shifting toward Roosevelt’s plan. For the power companies, it was time for “Plan B.” Quietly meeting with J.P. Morgan Bank in the summer of 1929, three major upstate New York power companies planned to merge into one giant company: Mohawk Hudson Power Corporation.

The modern day Mohawk Hudson Power Company was Niagara-Mohawk, which has since been purchased by National Grid.

Mohawk Hudson Power Corporation incorporated:

- Buffalo, Niagara & Eastern Power Corp.: Served 500 cities and towns including Buffalo. Niagara Falls supplied most of its power;

- Northeastern Power Corp.: Served communities along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence;

- Mohawk Hudson Power Corp.: Served Albany, Schenectady, Utica, Syracuse, and many other communities.

With such a merger, Roosevelt’s original plan to let upstate power companies compete to offer the best possible rates for hydro power were dashed. In fact, the power companies loved Roosevelt’s plan because as a combined entity, they’d profit handsomely from state taxpayers paying to construct hydro generating stations, saving them the trouble. Then as a monopoly cartel, they’d set rates artificially high, pocketing the proceeds. J.P. Morgan Bank would also get paid handsomely for helping make it all possible.

To add insult to injury, just two months later, Mohawk Hudson acquired another state giant — Frontier Power Corporation, which in the words of Time magazine, “set Roosevelt agog.”

Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York (Democrat) declared that the fact that 80% of New York State is now served by one hydro-electric corporation made it necessary for him once again to urge the Legislature (Republican) to create a body of public trustees to develop St. Lawrence water power for the people.

Roosevelt’s experience with the House of Morgan and the power utility trusts would be a lesson he would never forgive or forget. In fact, it culminated in his broadened vision to consider power an integral part of economic redevelopment after the start of the Great Depression later that year.

Roosevelt’s New Deal

Americans only came to terms with the impact of the Great Depression in 1930, months after the stock market crashed. What initially hurt Wall Street soon spread across the country in waves of bank failures, massive unemployment, a credit crunch, and rampant homelessness, poverty, and despair. What was bad in the city could be much worse in rural America.

Services for rural Americans were few and far between, and electric power was absolutely not one of them. The economic benefits of the boom years usually never made it to rural communities in the first place. Banks did manage to turn an excellent business convincing rural farmers to mortgage their farms in return for ready cash to acquire farm equipment, pay transportation costs to bring crops to market, and obtain other necessities. When the bust years arrived, more than a few farmers found themselves foreclosed and evicted from their own farms, seized by lenders to recoup their loans.

After witnessing thousands of farmers and other rural Americans displaced from their homes, Roosevelt embarked on wide-ranging reforms for rural America. One of the most important was rural electrification, designed to guarantee electricity to any rural American that wanted it. Through the New Deal, rural Americans would experience the benefits of modernization first-hand — bolstering farm production and development, increasing economic development, improving health and safety, and most importantly, make rural living economically self-sustainable.

After learning from his years as governor of New York, Roosevelt established some core principles for his rural-focused New Deal electrification program:

- Full electrical modernization of households defined the standard for quality of life, no matter where the households resided.

- Electrical modernization of farm productive processes, within the framework of planned production and marketing, would lower farm costs and return farms to prosperity.

- Electricity must be affordable to all households in quantities required for electrical modernization. Publicly owned and private utilities, lightened of their false capitalization by public regulation and the breakup of holding companies, would provide inexpensive electricity.

- Cheap electricity would make the redistribution of population and industry possible, because it could be transmitted long distances and sold at near cost to rural consumers.

President Roosevelt speaks to residents in Tupelo, Mississippi, the first city to benefit from the Tennessee Valley Authority

The mostly rural and poor Tennessee Valley region, covering 80,000 square miles in the southeastern United States, including almost all of Tennessee and parts of Mississippi, Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia was an obvious first choice for rural electrification. Tupelo, Mississippi was the first community to sign onto Roosevelt’s ambitious Tennessee Valley Authority plan to bring cheap power to a deprived region.

The results of electrification at reasonable prices were… electric. Widespread poverty wasn’t solved overnight, but evidence of social transformation was at hand. Americans from coast to coast were modernizing their homes, bringing in new electric appliances which fueled pre-war manufacturing, retail sales, and helped bring down unemployment. Many businesses were thrilled to participate in New Deal programs, which included stimulus spending to help Americans improve their homes.

The impact of New Deal programs for electricity development exist in every American home. The refrigerator replaced an ice-block powered icebox. Hand scrubbed laundry in a sink now agitated in a washing machine. The radio was made commonplace where electricity to power it was available. Mixers, blenders, toasters, and other small appliances made their entrance with the advent of widespread electric power. But the impacts go even further. Technology as Freedom, by Ronald Tobey, notes:

The New Deal in domestic electrical modernization worked an invisible revolution. The New Deal shifted the majority of American families to an asset strategy for economic security through state-enframed home ownership of electrically modern dwellings. Geographic mobility declined. Unrestrained domination of local politics by a locally resident real estate elite ended. Material accumulation based in the owner-occupied home created unprecedented material affluence. The dwellings modernized their occupants, as households rebuilt their social and labor relations around new technologies. Minority groups previously locked out of affluence gained the keys to their future. The New Deal created the 1950s.

Is ubiquitous broadband the electrification challenge of our age? Naysayers claim fast broadband is only useful for downloading entertainment products, often illegally. They suggest economic development doesn’t require fast broadband — any version of broadband is good enough. Worse yet, government involvement in it is suspect, according to these critics.

But after weeks of witnessing countless communities compete for Google’s Think Big With a Gig broadband project, it’s clear the clamor for affordable, fast broadband service is far more important than the naysayers would suggest.

Subscribe

Subscribe