July 8, 2019

July 8, 2019

Hon. Kathleen H. Burgess

Secretary to the Commission

New York State Public Service Commission

Three Empire State Plaza

Albany, NY 12223-1350

Re: 15-01446/15-M-0388 Joint Petition of Charter Communications and Time Warner Cable for Approval of a Transfer of Control of Subsidiaries and Franchises, Pro Forma Reorganization, and Certain Financing Arrangements – Settlement Proposal

Dear Secretary Burgess,

Stop the Cap!, a party in this proceeding that has regularly contributed to the record since the original application by Charter Communications to transfer control of cable systems formerly owned and operated by Time Warner Cable, is pleased to provide our comments regarding the April 19, 2019 proposed settlement between the Department of Public Service/Public Service Commission and Charter Communications, Inc.

Our organization and our members remain actively interested and engaged on this transaction and the impact it has had on consumers and businesses in New York State. We believe that all New Yorkers were harmed as a result of Charter’s lack of compliance with the 2016 Merger Order.

Stop the Cap! believes the existing settlement proposal lacks adequate compensation for the millions of New Yorkers that are now paying higher prices for internet service, receiving compromised service in the New York City area due to an ongoing, unsettled strike action, rural residents still waiting for Charter to meet its commitments to expand its network, and those low income New Yorkers that have been disadvantaged by the difficulty of obtaining affordable internet service. At the time of this submission, nearly half of Charter’s national footprint provides twice the internet speed New Yorkers now receive, making a mockery of the claim that Spectrum provides best-in-class service in this state.

Therefore, we believe the current settlement proposal as offered is insufficient and does not provide adequate compensation to New York consumers and businesses.

Cost Concerns and Charter’s Impact on New York’s Digital Divide

Stop the Cap! objected to the 2016 merger because of our fears it would result in higher prices for internet service for consumers in New York, exacerbating the digital divide. We believe there is now strong evidence to back our concerns.

Since the DPS/PSC issued the original 2016 Merger Order, New Yorkers now pay substantially more for internet service than was the case with Time Warner Cable. Although Charter has significantly raised broadband speeds in New York State, it has also reduced the number of budget-priced options ordinary customers have for broadband service.

In 2016, prior to the Merger Order, Time Warner Cable charged customers as follows (rates applicable to customers in Rochester, N.Y.)[1]:

- Everyday Low Price Internet ($14.99)

- Basic Internet ($49.99)

- Standard Internet ($59.99)

- Turbo ($69.99)

- Extreme ($79.99)

- Ultimate ($109.99)

In 2019, Spectrum offers faster speeds than Time Warner Cable, but at a higher cost[2]:

- Spectrum Internet ($65.99)

- Spectrum Ultra ($90.99)

- Spectrum Gig ($125.99)

The broadband options for low-income New Yorkers have been drastically reduced by Spectrum. Faster speed is of little concern to low income residents that cannot afford the service. New Yorkers saw their cable bills rise as a direct result of this merger, as we predicted. The minimum cost for standalone broadband service from Spectrum for the majority of consumers is now $65.99 a month, and the company has become far more reticent about negotiating customer retention deals that discount the cost of service than its predecessor Time Warner Cable. In fact, Charter CEO Thomas Rutledge made a point of promising to end the “Turkish bazaar” of pricing promotions at Time Warner Cable after the merger[3]. Customers are now subjected to “take it or leave it” pricing[4].

Spectrum’s concern for low income customers in New York is dubious. Stop the Cap! recommended, and the PSC adopted a condition in the 2016 Merger Order temporarily extending the availability of Time Warner Cable’s $14.99 “Everyday Low Price Internet” (ELP) tier of service, available on a standalone basis to any consumer without pre-qualification. However, after Spectrum announced its own plans and pricing, the company never significantly marketed the option of ELP service to its New York customers. In fact, while the company heavily promoted its own conditional Spectrum Internet Assist (SIA) package, consumers informed us they could not subscribe to ELP in New York because Charter customer service representatives misinformed them the service was no longer available, or they confused it with SIA and told them they were not qualified for discounted internet service. It is our testimony that only the most persistent and well-informed customers were likely to successfully sign up for the ELP program, often requiring multiple attempts to do so[5].

The differences between ELP and SIA are stark. ELP required no pre-qualification and customers could keep the package as long as they liked. SIA is limited to customers that qualify for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), the Community Eligibility Provision of the NSLP, or seniors 65 and over that qualify for Supplemental Security Income[6]. Customers must re-qualify at set intervals to continue eligibility, leaving out low income households without school-age children or seniors on limited incomes but lack SSI eligibility. More importantly, Charter protects its revenue stream by denying eligibility to all customers with pre-existing Spectrum internet service. To qualify, a customer would have to disconnect internet service for at least 30 days, have no outstanding debt with Charter within one year prior to applying for service, and once an SIA customer be sure not to have any outstanding debt with Charter subject to Charter’s “ordinary debt collection procedures.”[7] ELP service, in contrast, was available as an option at any time, to anyone.

Charter’s Speed Gap

New York residents do not uniformly benefit from the best in class service available from Charter Communications. Nearly half of Charter’s footprint outside of New York now offers customers entry-level download speeds of 200 Mbps at the same price most New Yorkers pay for 100 Mbps[8].

Failure to Comply With Rural Broadband Buildout Obligations

The PSC’s decision to rescind approval of the 2016 Merger Order between Time Warner Cable and Charter Communications was done after substantial evidence showed Charter had failed to meet the important obligations to rural New Yorkers required of it to make the merger meet the public interest test.

These failures were systemic and have compromised our rural economies by delaying much-needed internet access. It is for this reason that much of the settlement must be focused on correcting these deficiencies and, as a penalty for underperformance, broaden the number of required passings to deliver service to an even greater number of residents and businesses.

We welcome the settlement proposal to target penalties to help fund further broadband expansion. After years of talking to rural New York residents, it is clear New York’s rural broadband problem will continue after the conclusion of the state’s own broadband expansion program. We have heard from New Yorkers that are deeply concerned because the providers originally designated to serve their rural addresses have now refused to offer service or wrongly claim it will be made available by another provider. There is significant confusion and we fear many rural addresses are likely to “fall through the cracks” and end up serviced by no one.

Therefore, guaranteeing that rural New Yorkers have access to 21st century broadband service should be of the highest priority.

More than 78,000 New Yorkers have been assigned inferior internet access through HughesNet, a satellite internet provider[9]. HughesNet will allow those New Yorkers designated for satellite service through the Broadband Program Office (BPO) to use up to 100 GB of data per month before throttling service speeds to 1-3 Mbps for the balance of the billing period[10]. HughesNet also cannot guarantee to meet the FCC’s minimum speed definition of 25 Mbps and more importantly, provides an inadequate usage allowance[11].

Spectrum does not cap data usage or utilize speed throttles, while HughesNet severely throttles internet speeds of customers exceeding a data allowance we consider paltry. Recent research reports the average U.S. household now consumes 282.1 GB per month in areas where flat-rate internet service is offered. This leaves addresses designated for satellite service at a significant disadvantage[12].

The BPO has indicated that addresses assigned to the HughesNet program came as a result of a lack of suitable bids to service those addresses with traditional wireline service. There is clear evidence that providers are dissuaded from serving these high cost areas as a result of a lack of return on investment. Therefore, incentivizing Charter Communications to consider servicing as many of these addresses as practical is in the best interests of New Yorkers.

It is our view that cable broadband service is far superior to many current wireless, satellite, and copper-based DSL services, and we believe that technological capability should be a factor in considering whether to credit Charter for an overlapping new passing. We strongly recommend that Charter be encouraged in every way possible to extend service to as many customers currently designated for satellite internet service as possible. Although the proposed settlement does not punish Charter for extending service into these areas, it is reasonable to assume that the company would not otherwise extend service to these locations without receiving some direct or indirect financial benefit or subsidy. Therefore, we argue that Charter should be credited for any and all new passings in satellite-designated areas, without limit. However, we also believe the 30,000 minimum passing requirement is too low, as is the allowed designation of “substantial compliance” after passing 28,500 homes.

The exceptional amount of confidentiality surrounding Plans of Record among the different providers, including Charter, is not in the public interest and prevents impacted New Yorkers from fully participating in this important process. Since these areas have been historically underserved or unserved, there is little, if any, competitive risk by divulging the Plans of Record publicly. Charter’s rural buildout plans and progress reports should be publicly available. As it stands today, we remain unclear about how many already-passed or planned-to-be-passed homes are a part of the 30,000 the Commission proposes to count. Having that information is crucial to offering informed views about the proposed settlement.

With respect to wireline service overlap, we believe that consumers should benefit from the best possible service provider. We recognize that with limited funds available, duplicative service should be avoided. However, if Charter overlaps with another provider, and if the broadband speed Spectrum offers is superior to what is available from the incumbent wireline provider, it should receive credit for that passing even if in excess of 9,400 addresses, so long as that area is designated as rural and underserved.

Incremental Build Commitment

Stop the Cap! strongly approves of the settlement recommendation to establish a fund for supplementary broadband expansion beyond the original commitments defined in the 2016 Merger Order.

However, we offer some recommendations that we believe will make the fund’s purpose more practical to address the real-life experiences rural New Yorkers encounter when requesting that Charter extend service to a presently unserved address.

Charter Communications, like all cable companies, has a confidential formula to determine a reasonable return on investment when considering whether or not to expand service to a currently unserved address. Cable operators designate an amount the company is willing to pay out of pocket to cover construction/expansion costs. That number is often different for residential and commercial subscribers.

The proposed ceiling of $10,000 is very low in our opinion. Rural New York residents seeking Spectrum cable service are frequently quoted prices far in excess of this amount to extend service from a nearby served location. We believe this ceiling should be at least doubled to $20,000 and should be separate from the amount of money Charter routinely self-funds for qualified buildouts. For example, if Charter is traditionally willing to self-fund up to $2,500 of the cost of supplying service to a new residential or commercial customer, a project budget up to $22,500 would be acceptable to proceed, with $2,500 in funds coming from Charter and the remaining $20,000 coming from the Incremental Build Account.

We also recommend that any address rejected for consideration for service expansion for cost reasons be formally notified and offered an opportunity to participate in the process and permitted to optionally finance any cost in excess of the ceiling amount. The current proposal lacks any provision for the participation of residents and businesses in this process. At least some might choose to voluntarily participate in a cost-sharing opportunity to extend cable broadband service to their address.

Impact of Ongoing Strike in the New York City Area

For more than two years, at least 1,500 Spectrum employees affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 3 have been on strike in the New York City area. As a result, Spectrum customers have been subjected to a declining level of service as highly-qualified technicians remain off the job[13]. Charter Communications’ merger with Time Warner Cable was only approved in New York if it met a public interest test, and there is significant evidence New York City customers are not getting the level of service they would otherwise receive if there was no strike action[14].

As a result, the PSC should carefully study the impact of the strike on New York City customers and find any means available to compel a fair settlement and end this historically long labor dispute. Customers are caught in the middle, and there is evidence Charter may not be employing an entirely local workforce to service its customers in the New York City area. This strike would likely have not occurred had Time Warner Cable still been the incumbent cable provider.

Stop the Cap!’s Recommendations for a Revised Settlement Between Charter Communications and the Department of Public Service/Public Service Commission

- In recognition of the fact Charter has exacerbated the digital divide by pricing internet service higher than its predecessor, Charter must agree to further extend the availability of its Everyday Low Price Internet ($14.99/month) service to new customers for an additional five year period, reset existing New York customer pricing for this package to $14.99 for the same period, and publish a regular notice in bill statements about the availability of this tier, including the fact it is available to all customers on a standalone basis.

- In recognition of the fact Charter places unreasonable restrictions on qualifying for its Spectrum Internet Assist program, the settlement agreement should require that for the next five years Charter remove the restriction preventing New York customers from enrolling in the SIA program if they already have Spectrum internet service.

- In recognition of the fact Charter is not supplying all New York residents with best-in-class service, Charter must immediately boost the download speed of its basic Spectrum Internet package from the current 100 Mbps to 200 Mbps in all service areas in New York State, which matches the speed offered in nearly half of its national footprint. For a period of not less than five years, Charter must agree to provide New York State customers with access to any other speed improvements or upgrades as soon as they become available in any other state serviced by Charter.

- In recognition of the fact Charter has failed to meet its obligations to expand service to rural New York locations, the Commission should move forward with the revised buildout plan that includes additional new passings beyond what was specified in the 2016 Merger Order, and establish the proposed Incremental Build requirement and associated Spectrum-funded Build Account of not less than $6 million.

- In recognition of the fact New York addresses designated to receive HughesNet satellite internet service will be at a substantial disadvantage because of slower internet speeds and a usage allowance of 100 GB, well below the national data consumption average, the DPS/PSC do everything possible to compel and/or encourage Charter Communications to extend its service to overlap satellite-designated areas and receive credit towards its buildout requirement for doing so.

- In recognition of the fact some wireline providers offer superior internet service over others, any formula counting the number of homes provided overlapping wireline internet coverage from Spectrum and an existing incumbent wireline provider should consider the capabilities of both providers. If Spectrum offers superior internet speeds, it should be counted as a new passing. If the incumbent matches or exceeds Spectrum’s available speeds, Spectrum’s new overlapped passing should not be counted.

- In recognition of the fact that rural consumers and businesses have been left in the dark about the status of their designated internet provider, Plans of Record from Charter Communications under this settlement, as well as other BPO-fund recipients should be made public, including the name and contact information of the designated provider and estimated date of service availability.

- In recognition of the fact cable companies designate a maximum amount they are willing to pay out of pocket to establish service at a new address/location, that amount should continue to be paid out of pocket by Charter, with additional expenses above that amount, up to $20,000, covered by the Incremental Build Account if designated as an incremental buildout project. Any address considered for a new passing must be notified in advance if the proposal would otherwise be rejected because the estimated cost to extend service is beyond the $20,000 ceiling and the amount Charter would typically pay out of pocket. That resident or business would then be offered the opportunity to optionally pay the specified excess amount within a reasonable period of time to allow the project to move forward.

- In recognition of the fact that Charter technicians and employees in the New York City area have been on strike for over two years, potentially impacting the quality of service Spectrum customers receive in the area, the DPS/PSC should study the impact of the strike on service quality and do all it can to encourage Charter to settle the strike at the earliest opportunity.

We appreciate the Commission and its staff’s hard work on this matter, and hope you will seriously consider our input and ideas, demonstrating once again that the New York Public Service Commission takes its obligations to the citizens of New York seriously.

Very truly yours,

Phillip M. Dampier

President and Founder

Stop the Cap!

[1] http://stopthecap.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/twc-2016-rate-card-rochester.jpg

[2] http://stopthecap.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Charter-Spectrum-2019-Rate-Card-Information.pdf

[3] https://www.fiercevideo.com/cable/charter-s-rutledge-pre-merger-twc-offered-a-turkish-bazaar-promo-offers

[4] https://www.syracuse.com/news/2017/05/thousands_of_time_warner_cable_video_customers_flee_spectrums_higher_prices.html

[5] https://www.reddit.com/r/Spectrum/comments/ab02cu/spectrum_deceiving_customers_about_everyday_low/

[6] https://www.spectrum.com/browse/content/spectrum-internet-assist.html

[7] https://www.spectrum.com/browse/content/spectrum-internet-assist.html

[8] https://newsroom.charter.com/news-views/2018-twas-the-year-of-gig-50-million-locations-and-counting/

[9] https://nysbroadband.ny.gov/new-ny-broadband-program/phase-3-awards

[10] https://www.hughesnet.com/node/102201

[11] http://legal.hughesnet.com/SubAgree-03-16-17.cfm

[12] https://www.telecompetitor.com/report-u-s-household-broadband-data-consumption-hit-268-7-gigabytes-in-2018/

[13] http://amsterdamnews.com/news/2017/aug/10/spectrum-strike-affects-us-all/

[14] https://www.pressconnects.com/story/money/2018/08/08/charter-spectrum-cable-new-york-consumers/898780002/

Subscribe

Subscribe

But like many Wall Street analysts who complain about almost any significant investment or spending, once a company has gone ahead and spent the money, analysts start looking at how those companies are monetizing those upgrades to recover the investment, boost revenue, and maximize shareholder value. Moffett flipped on a dime from being a critic of cable’s spending to commenting on how well the cable industry was now positioned to lead the telecom industry.

But like many Wall Street analysts who complain about almost any significant investment or spending, once a company has gone ahead and spent the money, analysts start looking at how those companies are monetizing those upgrades to recover the investment, boost revenue, and maximize shareholder value. Moffett flipped on a dime from being a critic of cable’s spending to commenting on how well the cable industry was now positioned to lead the telecom industry.

Project Lightspeed was developed by SBC in 2004 and later renamed AT&T U-verse in time for its commercial launch in 2006. AT&T chose a fiber to the neighborhood approach, leaving intact existing copper phone wiring already in place in neighborhoods and homes. U-verse was capable (at the time) of delivering just over 20 Mbps internet service while customers also watched TV, and/or made a phone call. The advantage of U-verse was that it was cheaper to deploy across AT&T’s more sprawling local telephone territories than fiber all the way to each customer’s home.

Project Lightspeed was developed by SBC in 2004 and later renamed AT&T U-verse in time for its commercial launch in 2006. AT&T chose a fiber to the neighborhood approach, leaving intact existing copper phone wiring already in place in neighborhoods and homes. U-verse was capable (at the time) of delivering just over 20 Mbps internet service while customers also watched TV, and/or made a phone call. The advantage of U-verse was that it was cheaper to deploy across AT&T’s more sprawling local telephone territories than fiber all the way to each customer’s home. Moffett’s 2008 calculations argued that Verizon would lose $769 on each FiOS customer signing up for service. AT&T U-verse would come close to breaking even, but not generate much in the way of profit for AT&T. After determining that, he was a frequent and vocal critic of upgrade efforts, particularly in the case of FiOS. Verizon argued his calculations were wrong and that the company was pleased with the progress of its fiber buildout. But Moffett claimed vindication when Verizon

Moffett’s 2008 calculations argued that Verizon would lose $769 on each FiOS customer signing up for service. AT&T U-verse would come close to breaking even, but not generate much in the way of profit for AT&T. After determining that, he was a frequent and vocal critic of upgrade efforts, particularly in the case of FiOS. Verizon argued his calculations were wrong and that the company was pleased with the progress of its fiber buildout. But Moffett claimed vindication when Verizon  For example, Mr. Moffett spit nails over the cable industry’s “waste” of $100 billion on system rebuilds in the 1990s, but by the late 2000s he was

For example, Mr. Moffett spit nails over the cable industry’s “waste” of $100 billion on system rebuilds in the 1990s, but by the late 2000s he was  Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases.

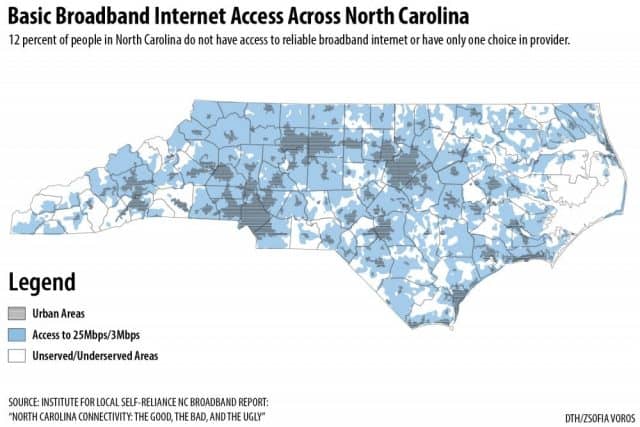

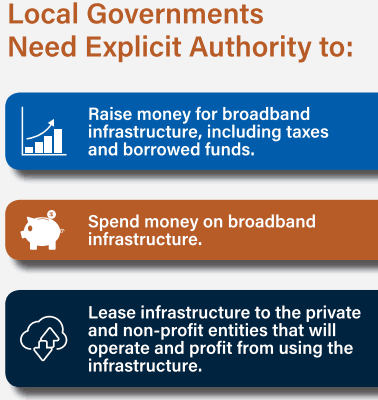

Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases. A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs.

A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs. In North Carolina,

In North Carolina,

Windstream announced this week it was ditching EarthLink, the internet service provider it acquired in 2017 that has been around since the days of dial-up, in a $330 million cash deal.

Windstream announced this week it was ditching EarthLink, the internet service provider it acquired in 2017 that has been around since the days of dial-up, in a $330 million cash deal. As EarthLink’s balance sheet increasingly exposed the high wholesale cost of the company’s growing number of DSL and cable internet customers, executives calmed Wall Street with predictions that EarthLink’s wholesale costs would drop as networks matured and the costs to deploy DSL and cable internet declined. The phone and cable industry had other ideas.

As EarthLink’s balance sheet increasingly exposed the high wholesale cost of the company’s growing number of DSL and cable internet customers, executives calmed Wall Street with predictions that EarthLink’s wholesale costs would drop as networks matured and the costs to deploy DSL and cable internet declined. The phone and cable industry had other ideas.

After the inspector general of the Federal Communications Commission opened an investigation into FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s close relationship with executives at Sinclair Broadcasting, Pai stopped returning Sinclair’s phone calls and refused any further meetings with America’s largest local TV station owner, at least until last Tuesday when Pai called Sinclair’s general counsel to say its multi-billion dollar merger with Tribune Media was in trouble.

After the inspector general of the Federal Communications Commission opened an investigation into FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s close relationship with executives at Sinclair Broadcasting, Pai stopped returning Sinclair’s phone calls and refused any further meetings with America’s largest local TV station owner, at least until last Tuesday when Pai called Sinclair’s general counsel to say its multi-billion dollar merger with Tribune Media was in trouble.