March was a big month for lobbyists visiting the Federal Communications Commission, which opened the doors to wireless special interest groups for “ex parte” meetings with agency staffers that, in turn, brief the three Republicans and two Democrats that serve as FCC commissioners.

March was a big month for lobbyists visiting the Federal Communications Commission, which opened the doors to wireless special interest groups for “ex parte” meetings with agency staffers that, in turn, brief the three Republicans and two Democrats that serve as FCC commissioners.

Last month’s ex parte filings reveal strong evidence of a coordinated, well-financed campaign by America’s wireless operators and cable companies to get the FCC to ease off regulations governing forthcoming 5G networks, particularly with respect to where tens of thousands of “small cell” antennas will be installed to deliver the service.

Four industry trade groups and companies are part of the concerted campaign to scale back third party control over where 5G infrastructure will end up. Some want to strip local governments of their power to oversee where 5G infrastructure will be placed, while others seek the elimination of laws and regulations that give everyone from historical societies to Native American tribes a say where next generation wireless infrastructure will go. The one point all four interests agree on — favoring pro-industry policies that give wireless companies the power to flood local communities with wireless infrastructure applications that come with automatic approval unless denied for “good cause” within a short window of time, regardless of how overwhelmed local governments are by the blizzard of paperwork.

Here are the big players:

The Competitive Carriers Association (CCA)

The Competitive Carriers Association (CCA)

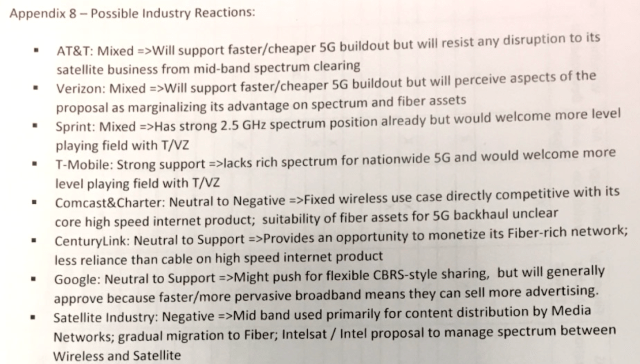

The CCA is primarily comprised of rural, independent, and smaller wireless companies. In short, a large percentage of wireless companies not named AT&T or Verizon Wireless are members of CCA. The CCA’s chief goal is to protect the interests of their members, who lack the finances and political pull of the top two wireless companies in the U.S. CCA lobbyists met ex parte with the FCC multiple times, submitting seven filings about their March meetings.

CCA’s top priority is to get rid of what they consider burdensome regulations about where members can place cell towers and antennas. They also want a big reduction in costly environmental, tribal, and historic reviews that are often required as part of a wireless buildout application. CCA lobbyists argue that multiple interests have their hands on CCA member applications, and fees can become “exorbitant” even before some basic reviews are completed. The CCA claims there have been standoffs between competing interests creating delays and confusion.

Costs are a relevant factor for most CCA members, which operate regional or local wireless networks often in rural areas. Getting a return on capital investment in rural wireless infrastructure can  be challenging, and CCA claims unnecessary costs are curtailing additional rural expansion.

be challenging, and CCA claims unnecessary costs are curtailing additional rural expansion.

NCTA – The Internet & Television Association

The large cable industry lobbyist managed to submit eight ex parte filings with the FCC in March alone, making the NCTA one of the most prolific frequent visitors to the FCC’s headquarters in Washington.

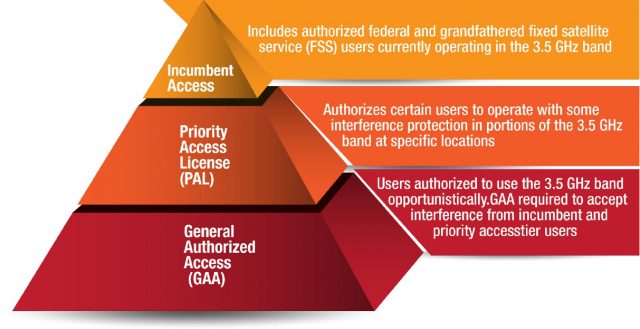

The NCTA was there to discuss the Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) band, which is of particular interest to cable companies like Charter Communications, which wants to get into the wireless business on its own terms. Cable lobbyists, under the pretext of trying to avoid harmful interference, want to secure a large percentage of the CBRS band for their licensed use, at the expense of unlicensed consumers and their wireless industry competitors.

The cable industry wants CBRS spectrum to be wide, spacious, and contiguous for its cable industry members, which should open the door to faster speeds. The lobbyists want to make life difficult for unlicensed use of the band, potentially requiring cumbersome use regulations or costly equipment to verify a lack of interference to licensed users. They also want their traffic protected from other licensed users’ interference.

CTIA – The Wireless Association

CTIA – The Wireless Association

The wireless industry’s largest lobbying group made multiple visits to the FCC in March and filed 10 ex parte communications looking for a dramatic reduction in local zoning and placement laws for the next generation of small cells and 5G networks.

The CTIA has been arguing with tribal interests recently. Tribes want the right to review cell tower placement and the environmental impacts of new equipment and construction. The CTIA wants a sped-up process for reviewing cell tower and site applications with a strict 30-day time limit, preferably with automatic approval for any unconsidered applications after the clock runs out. Although not explicitly stated, there have been grumblings in the past that tribal interests are inserting themselves into the review process in hopes of collecting application and review fees as a new revenue source. Wireless companies frequently question whether tribal review is even appropriate for some applications.

Sprint has had frequent run-ins with tribal interests demanding several thousand dollars for each application’s review under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), which is supposed to protect heritage and historical sites.

In Houston, Sprint deployed small cells around the NRG Stadium, but found itself paying fees to at least a dozen Indian Tribal Nations as part of the NHPA. The NHPA opens the door to a lot of Native Americans interests because of how the law is written. Any Tribal Nation can express an interest in a project, even when it is to be placed on public or private property that is not considered to be tribal land. In Houston, Sprint found itself paying $6,850 per small cell site, not including processing fees, which raised the cost to $7,535 per antenna location. Those fees only covered tribal reviews, not the cost of installation or equipment. Some tribes offered better deals than others. The Tonkawa Tribe has 611 remaining members, mostly in Oklahoma. But they sought and got $200 in review fees for the 23 small cell sites deployed around the stadium. The Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma, not Texas, charged $1,500 for the 23 applications it reviewed.

Sprint complains it has paid millions in such fees over the last 13 years and no tribe to date has ever asked to meet with Sprint or suggest one of its towers or cell sites would intrude on historic or tribal property.

“Tribal Nations are continuing to demand higher fees and designate larger and larger areas of interest,” says Sprint. “At present, there are no constraints on the amount of fees a Tribal Nation may require or the geographic areas for which it can require payment for review. The tribal historic review process remains in place even in situations—such as utility rights-of-way—where the Commission has exempted state historic review.”

The CTIA wants major changes to the NHPA and other regulations regarding cell tower and antenna placement before the stampede of 5G construction begins.

Verizon

Verizon

Verizon has been extremely busy visiting with the FCC during the month of March, filing 10 ex parte communications, also complaining about the tribal reviews of wireless infrastructure.

Verizon argues it wants to expand wireless service, not effectively subsidize Native American tribes.

“The draft order’s provisions to streamline tribal reviews for larger wireless broadband facilities will likewise speed broadband deployment and eliminate costs, thus freeing up resources that can, in turn, be used to deploy more facilities,” Verizon argued in one filing.

Verizon has also been carefully protecting its most recent very high frequency spectrum buyouts. It wants the FCC to force existing satellite services to share the 29.1-29.25 GHz band for 5G wireless internet. Verizon has a huge 150 MHz swath of spectrum in this band, allowing for potentially extremely high-speed wireless service, even in somewhat marginal reception areas.

“Verizon assured the commission that even when sharing with other services, we would be able to make use of the 150 MHz of spectrum in this block to provide high-speed broadband service to American consumers,” said one filing.

Subscribe

Subscribe The Federal Communications Commission is pushing hard to free up additional spectrum in some unlikely extremely high frequency ranges — some at 95 GHz or higher, for the next generation of wireless services.

The Federal Communications Commission is pushing hard to free up additional spectrum in some unlikely extremely high frequency ranges — some at 95 GHz or higher, for the next generation of wireless services. There are proposals and counter proposals from the satellite industry and wireless companies over how to manage sharing this band. Most are coalescing around the idea of sequestering 100 MHz of spectrum at the low-end of the band and using 3700-3800 MHz for high-speed wireless broadband. Some want satellite operators to clear out of this section of frequencies voluntarily, others propose compensation similar to what was given to television stations to relocate their channel positions. Google is pushing for a plan that would offer mobile 5G service in large urban areas and 25 Mbps – 1 Gbps fixed wireless broadband in rural and residential areas.

There are proposals and counter proposals from the satellite industry and wireless companies over how to manage sharing this band. Most are coalescing around the idea of sequestering 100 MHz of spectrum at the low-end of the band and using 3700-3800 MHz for high-speed wireless broadband. Some want satellite operators to clear out of this section of frequencies voluntarily, others propose compensation similar to what was given to television stations to relocate their channel positions. Google is pushing for a plan that would offer mobile 5G service in large urban areas and 25 Mbps – 1 Gbps fixed wireless broadband in rural and residential areas. Many agencies contemplating use of this band discovered equipment that supported 4.9 GHz was hard to find and extremely expensive. Most public safety agencies seeking grants or other funding to improve their communications equipment opted to transition to digital P25 networks that operate on much lower frequencies and use equipment that is now widely available and, in comparison, much cheaper. Many agencies are conservative about using new technology as well, concerned a communications failure could cost the life of a fire or police responder. As a result, of the 90,000 organizations certified for licenses in this band, only 3,174 have been granted. That represents a take rate of just 3.5%. The band, as one might expect, is effectively dead in most areas, underutilized in others.

Many agencies contemplating use of this band discovered equipment that supported 4.9 GHz was hard to find and extremely expensive. Most public safety agencies seeking grants or other funding to improve their communications equipment opted to transition to digital P25 networks that operate on much lower frequencies and use equipment that is now widely available and, in comparison, much cheaper. Many agencies are conservative about using new technology as well, concerned a communications failure could cost the life of a fire or police responder. As a result, of the 90,000 organizations certified for licenses in this band, only 3,174 have been granted. That represents a take rate of just 3.5%. The band, as one might expect, is effectively dead in most areas, underutilized in others. Although the 28 GHz band has many licensed users already, the 24 GHz band does not, and the wireless industry is interested in grabbing vast swaths of spectrum in this band for 5G home broadband. Known as “millimeter wave spectrum,” these two bands are expected to be a big part of the 5G fixed wireless services being planned by some carriers. Verizon acquired Straight Path late in 2017, which had collected a large number of licenses for this frequency range. Today, Verizon holds almost 30% of all currently licensed millimeter wave spectrum, an untenable situation if you are AT&T, T-Mobile, or Sprint. T-Mobile has been the most aggressive seeking more spectrum to compete with Verizon in this frequency range, and has purchased almost 1,150 MHz covering Ohio for use with a 5G project the company is working on.

Although the 28 GHz band has many licensed users already, the 24 GHz band does not, and the wireless industry is interested in grabbing vast swaths of spectrum in this band for 5G home broadband. Known as “millimeter wave spectrum,” these two bands are expected to be a big part of the 5G fixed wireless services being planned by some carriers. Verizon acquired Straight Path late in 2017, which had collected a large number of licenses for this frequency range. Today, Verizon holds almost 30% of all currently licensed millimeter wave spectrum, an untenable situation if you are AT&T, T-Mobile, or Sprint. T-Mobile has been the most aggressive seeking more spectrum to compete with Verizon in this frequency range, and has purchased almost 1,150 MHz covering Ohio for use with a 5G project the company is working on.

AT&T’s attempt to avoid oversight and enforcement of consumer protection laws by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

AT&T’s attempt to avoid oversight and enforcement of consumer protection laws by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)  “AT&T promised its customers ‘unlimited’ data, and in many instances, it has failed to deliver on that promise,” said former FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez in 2014. “The issue here is simple: ‘unlimited’ means unlimited.”

“AT&T promised its customers ‘unlimited’ data, and in many instances, it has failed to deliver on that promise,” said former FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez in 2014. “The issue here is simple: ‘unlimited’ means unlimited.”

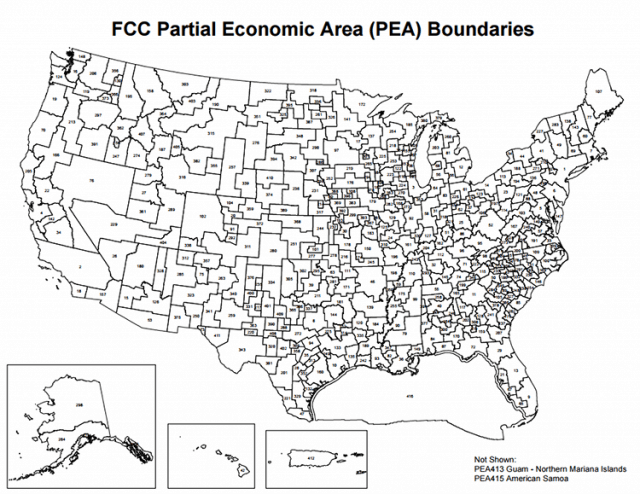

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.