“We just don’t see the need of delivering [gigabit broadband] to consumers.” — Irene Esteves, former chief financial officer, Time Warner Cable, February 2013

“We just don’t see the need of delivering [gigabit broadband] to consumers.” — Irene Esteves, former chief financial officer, Time Warner Cable, February 2013

“For some, the discussion about the broadband Internet seems to begin and end on the issue of ‘gigabit’ access. The issue with such speed is really more about demand than supply. Most websites can’t deliver content as fast as current networks move, and most U.S. homes have routers that can’t support the speed already available.” — David Cohen, chief lobbyist, Comcast Corp., May 2013

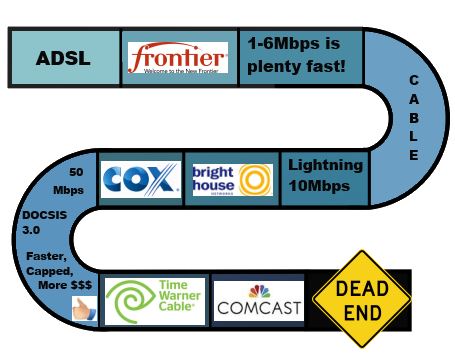

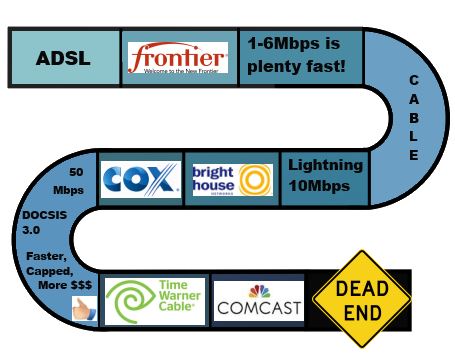

“We don’t focus on megabits, we don’t focus on gigabits, we focus on activities. We go to the activity set to get a sense of what customers are actually doing and the majority of our customers fit into that 6Mbps or less category.” — Maggie Wilderotter, CEO, Frontier Communications, May 2013

“It would cost multiple billions” to upgrade Cox’s network to offer gigabit speeds to all its customers. — Pat Esser, CEO, Cox Communications, Pat Esser, chief executive of Cox Communications Inc., January 2013

“The problem with [matching Google Fiber speeds] is even if you build the last mile access plant to [offer gigabit speeds], there is neither the applications that require that nor a broader Internet backbone and servers delivering at that speed. It ends up being more about publicity and bragging. There has been a whole series of articles in the paper about ‘I’m a little startup business and boy it is really great I can get this’ and my reaction is we already have plant there that can deliver whatever it is they are talking about in those articles, which is usually not stuff that requires that high-speed.” — Glenn Britt, CEO, Time Warner Cable, December 2012

“Residential customers, at this time, do not need the bandwidth offered with dedicated fiber – however, Bright House has led the industry in comprehensively deploying next-generation bandwidth services (DOCSIS 3.0) to its entire footprint in Florida – current speeds offered are 50Mbps with the ability to offer much higher. We provision our network according to our customers’ needs.” – Don Forbes, Bright House Networks, February 2011

‘Charter [Cable] is not seeing enough demand to warrant extending fiber to small and medium-sized businesses — and certainly not to every household.’ — “Speedier Internet Rivals Push Past Cable“, New York Times, Jan. 2, 2013

Unless you live in Kansas City, Austin, in a community where public broadband exists, or where Verizon FiOS provides its fiber optic service, chances are your broadband speeds are not growing much, but are getting more expensive. The only thing innovative coming from the local phone or cable company is a constant effort to convince customers they don’t need faster Internet access anyway.

At least until a competitor threatens to shake up the comfortable status quo.

Time Warner Cable claims they are perfectly comfortable offering residential customers no better than 50/5Mbps, except in markets like Kansas City (and soon in Texas) where 100Mbps is more satisfying. Why is a glass Time Warner claims is full to the brim everywhere else in the country only half-full in Kansas City? Google Fiber might be the answer. It offers 1,000/1,000Mbps service for less money than Time Warner used to charge for 50Mbps service, and Google is also headed to Austin.

AT&T scoffed at following Verizon into the world of fiber optic broadband, where broadband speeds are limited only by the possibilities. Instead, they built their half-fiber, half-Alexander Graham Bell-era copper wire hybrid network on the cheap and ended up with broadband speeds topping out around 24Mbps, at least in a perfect AT&T world, assuming everything was ideal between your home and their central office.

AT&T scoffed at following Verizon into the world of fiber optic broadband, where broadband speeds are limited only by the possibilities. Instead, they built their half-fiber, half-Alexander Graham Bell-era copper wire hybrid network on the cheap and ended up with broadband speeds topping out around 24Mbps, at least in a perfect AT&T world, assuming everything was ideal between your home and their central office.

At the time U-verse was first breaking ground, cable broadband’s “good enough for you” top Internet speed was typically 10-20Mbps. Now that incrementally faster cable Internet speeds are available from recent DOCSIS 3.0 cable upgrades, AT&T is coming back with an incremental upgrade of its own, to deliver around 75Mbps.

It is still slower than cable, but AT&T thinks it is fast enough for their customers, except in Austin, where Google Fiber provoked the company to claim it would build its own 1,000Mbps fiber network to compete (if it got everything on its Christmas Wish List from federal, state, and local governments).

Are you starting to see a trend here? Competition can turn providers’ investment frowns upside down and get customers faster Internet access.

Wilderotter: Most of our customers are satisfied with 6Mbps broadband.

In rural markets were Frontier Communications faces far less competition from well-heeled cable companies, the company can claim it doesn’t believe most of its customers need north of 6Mbps to do important things on the Internet. If they did, where would they go to do them?

Where Comcast and AT&T directly compete, major Internet speed increases are a matter of “why bother – who needs them.” Comcast is more generous where it faces down Verizon FiOS. AT&T also knows the clock is ticking where Google Fiber is coming to town.

Verizon FiOS, Google Fiber, and a number of community-owned fiber to the home broadband networks like EPB in Chattanooga and Greenlight in Wilson, N.C. seem more interested in boosting speeds to build market share, increase revenue to cover their expenses, and make a marketing point their networks are superior. They respond to requests for speed upgrades differently — “why not?”

Verizon figured out offering 50/25Mbps service was simple to offer and easy to embrace. Two clicks on a FiOS remote control and $10 more a month gets a major speed upgrade for basic Internet customers that used to get 15/5Mbps service. Verizon management reports they are pleased with the number of customers signing up.

In Chattanooga, Tenn. EPB Fiber offered gigabit Internet service because, in the words of its managing director, “it could.” The community-owned utility did not even know how to price residential gigabit service when it first went on offer, but the costs to EPB to offer those speeds are considerably lower over fiber to the home broadband infrastructure.

Broadband customers in Chattanooga, Kansas City and Austin are not too different from customers in Knoxville, Des Moines, and Houston. But the available broadband speeds in those cities sure are.

LUS Fiber in Lafayette, La. changed the song Cox was singing about their ‘adequate’ broadband speeds. Earlier this year, Cox unveiled up to 150/25Mbps service to cut the number of departing customers headed to the community owned utility, already offering those speeds.

Convincing Wall Street that spending money to upgrade networks to next generation technology will earn more money in the long run has failed miserably as a strategy.

“Competitors have been overbuilding, investors are wondering where the returns are,” said Mark Ansboury, president and co-founder of GigaBit Squared. “What you’re seeing is an entrenchment, companies leveraging what they already have in play.”

With North American broadband prices rising, and some cable companies earning 90-95% margins selling broadband, one might think there is plenty of money available to spend on broadband upgrades. Instead, investors are receiving increased dividend payouts, executive compensation packages are swelling as a reward for maximizing shareholder value, and many companies are buying back their stock, refinancing or paying off debt instead of pouring money into major network upgrades.

That is not true in Europe, where providers are making headlines with major network improvements and speed increases, all while charging much less than what North Americans pay for broadband service.

UPC Netherlands is Holland’s second biggest cable company and is in the middle of a broadband speed war with fiber to the home providers.

In the Netherlands, the very concept of Google Fiber’s affordable gigabit speeds terrify cable operators like UPC Netherlands, especially when existing fiber to the home providers in the country are taking Google’s cue and advertising gigabit service themselves. UPC rushed to dedicate up to 16 bonded cable channels to boost cable broadband speeds to 500Mbps in recent field trials, without giving any serious thought to the cable operators in the United States that argue customers don’t need or want the faster Internet speeds fiber offers.

“We had to address it head on very recently because of the fiber (competition)” said vice president of technology Bill Warga. “The company is called Reggefiber in the Netherlands. What they’re touting is a 1Gbps service, [the same speed] upstream and downstream. We came out with 500Mbps service. We had to build a special modem because (DOCSIS) 3.1 chips aren’t out yet. We had to double up on the chips in the modem and put it out there because we had to have a competing product, if anything just in the press. That was a reaction but that tells you how quickly in a marketplace that something can move.”

Despite that, groupthink among cable industry attendees back home at the SCTE Rocky Mountain Chapter Symposium agreed that Google Fiber was a political and marketing stunt, “since the majority of users don’t need those types of speed.”

Who does need and want 500Mbps? Executives at UPC, who have it installed in their homes, admits Warga. But cost can also impact consumer demand. Currently, the most popular legacy UPC broadband package offers 25Mbps for €25 ($32.50). The company now sells 60/6Mbps for €52,50 ($48.75), 100/10Mbps for €42,50 ($55.25) or 150-200/10Mbps for €52,50 ($68.25).

Warga also admits the competition has put UPC in a speed race, and boosted speeds are coming fast and furious.

“They’ll come in and say they’re 100, or 101Mbps we’ll come back and say we’re 110 or 120, or 130Mbps,” Warga said. “It’s a bit of a cat and mouse game, but we always feel like we can be ahead. For us DOCSIS 3.1 can’t come soon enough.”

[flv width=”640″ height=”367”]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WSJ Cable Broadband Speeds 1-13.flv[/flv]

The Wall Street Journal investigates why cable companies are getting stingy with broadband speed upgrades while gigabit fiber networks are springing up around the country. (4 minutes)

Subscribe

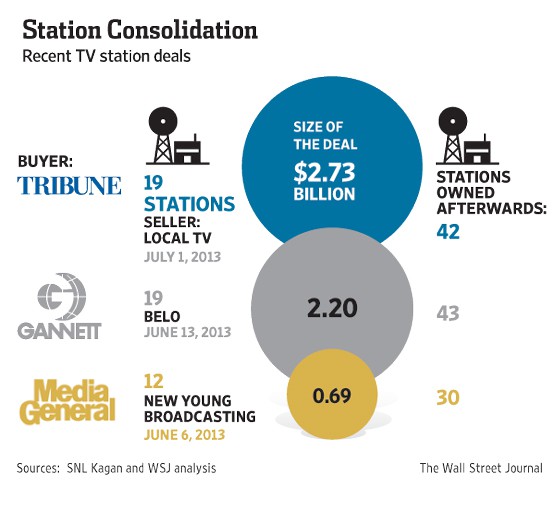

Subscribe It expects to pay off the loans and generate returns from the “significant free cash flow” generated by the stations.

It expects to pay off the loans and generate returns from the “significant free cash flow” generated by the stations. Tribune is not alone bulking up the number of stations they own and control. Last month Gannett nearly doubled its portfolio from 23 to 43 stations with the acquisition of Belo’s TV stations for $1.5 billion in cash and agreeing to cover $715 million in accumulated debt.

Tribune is not alone bulking up the number of stations they own and control. Last month Gannett nearly doubled its portfolio from 23 to 43 stations with the acquisition of Belo’s TV stations for $1.5 billion in cash and agreeing to cover $715 million in accumulated debt.

“We just don’t see the need of delivering [gigabit broadband] to consumers.” —

“We just don’t see the need of delivering [gigabit broadband] to consumers.” —  AT&T scoffed at following Verizon into the world of fiber optic broadband, where broadband speeds are limited only by the possibilities. Instead, they built their half-fiber, half-Alexander Graham Bell-era copper wire hybrid network on the cheap and ended up with broadband speeds topping out around 24Mbps, at least in a perfect AT&T world, assuming everything was ideal between your home and their central office.

AT&T scoffed at following Verizon into the world of fiber optic broadband, where broadband speeds are limited only by the possibilities. Instead, they built their half-fiber, half-Alexander Graham Bell-era copper wire hybrid network on the cheap and ended up with broadband speeds topping out around 24Mbps, at least in a perfect AT&T world, assuming everything was ideal between your home and their central office.

Malone also thinks it is time to discard reliance on cable television to bring home the revenue and profits Wall Street expects. The industry should instead turn its earning attention to broadband, a product few Americans can live without. Malone believes the cable industry is not only positioned to control content distributed on its TV Everywhere online video platform for authenticated cable subscribers, but also have a say in competing content from Netflix, among others, which are totally reliant on the broadband pipes provided by ISPs.

Malone also thinks it is time to discard reliance on cable television to bring home the revenue and profits Wall Street expects. The industry should instead turn its earning attention to broadband, a product few Americans can live without. Malone believes the cable industry is not only positioned to control content distributed on its TV Everywhere online video platform for authenticated cable subscribers, but also have a say in competing content from Netflix, among others, which are totally reliant on the broadband pipes provided by ISPs. Among the top recipients: Comcast, which collects $25-30 million a year and Time Warner Cable, which nets “tens of millions of dollars” from Google, Microsoft, and Facebook.

Among the top recipients: Comcast, which collects $25-30 million a year and Time Warner Cable, which nets “tens of millions of dollars” from Google, Microsoft, and Facebook.