The next name of Time Warner Cable?

Charter Communications is laying the foundation for a leveraged buyout of Time Warner Cable before the end of the year in a deal that could leave Time Warner Cable’s broadband customers with Charter’s usage caps.

Reuters reported discussions between the two companies grew more serious after last week’s revelation a poor third quarter left TWC with 308,000 fewer subscribers.

Charter is relying on guidance from Goldman Sachs to structure a financing deal likely to leave Charter in considerable debt. Charter Communications emerged from bankruptcy in 2009 and is the country’s tenth largest cable operator, estimated to be worth about $13 billion. Time Warner Cable is the second largest cable operator and is worth more than $34 billion.

The disparity between the two companies has kept Time Warner Cable resistant to a deal with Charter, stating it would not be beneficial to shareholders. Charter executives hope to eventually win shareholder support for a buyout stressing the significant cost savings possible from a combined operation, particularly for cable programming.

The deal would likely end Time Warner Cable as a brand and leave Charter Communications CEO Thomas Rutledge in charge of a much larger cable company. Pricing and packaging decisions are usually made by the buyer, which could bring faster broadband speeds to Time Warner customers, but also usage caps already in place at Charter.

John Malone’s War on Customers

Malone

Cable billionaire John Malone, former CEO of Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) — America’s largest cable operator in the 1980s — believes consolidation is critical to the future of a cable business facing competition from phone companies and cord cutting. Malone’s Liberty Media, which now holds a 25% stake in Charter, is currently buying and consolidating cable operators in Europe. Malone’s post-consolidation vision calls for only two or three cable operators in the United States.

Malone’s quest for consolidation is nothing new.

Under his leadership, TCI eventually became the country’s biggest cable operator, but one often accused of poor service and high prices. More than a decade of complaints from customers eventually attracted the attention of the U.S. Congress, which sought to rein in the industry with the 1992 Cable Act — legislation that lightly regulated rental fees for equipment and the price of the company’s most-basic television tier.

Despite the fact consumer advocates didn’t win stronger consumer protection regulations, TCI was still incensed it faced a new regulatory environment that left its hands tied. One executive at a TCI subsidiary advocated retaliation with broad rate increases for unregulated services to make up any losses from mandated rate cuts.

A 1993 internal TCI memo obtained by the Washington Post instructed TCI system managers and division vice presidents to increase prices charged for customer service calls and add new fees for common installation services the company used to offer for free. TCI’s Barry Marshall recommended charging for as many “transaction” services as possible — like hooking up VCR’s, running cable wire, and programming remote controls for confused customers.

“We have to have discipline,” Marshall wrote. “We cannot be dissuaded from the [new] charges simply because customers object. It will take awhile, but they’ll get used to it. The best news of all is we can blame it on re-regulation and the government now. Let’s take advantage of it!”

Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) was the nation’s largest cable operator. Later known as AT&T Cable, the company was eventually sold to Comcast.

The FCC’s interim chairman at the time — James Quello, charged with monitoring the cable industry, was not amused.

“It typifies the attitude of cable companies engaging in creative pricing and rate increases to evade the intent of Congress and the FCC,” Quello said. “There is little doubt that the cable industry has an economic stake in discrediting the congressional act they vehemently and unsuccessfully opposed.”

Marshall defended his internal memo, although admitted it was inartfully written and was not intended for the public. Revelation of a damaging memo like this would normally lead to a quiet resignation by the offending author, but not at John Malone’s TCI, a company with a reputation for being difficult.

Mark Robichaux’s 2005 book, Cable Cowboy: John Malone and the Rise of the Modern Cable Business , was even less charitable.

, was even less charitable.

Robichaux describes Malone as a “complicated hero,” at least for investors for whom he was willing to ignore banking rules and creatively interpret tax law. Robichaux wrote Malone’s idea of customer service was to ‘charge as much as you can, but spend as little as you can get away with.’

TCI’s top priority was to keep up the cable business as an “insular cartel.” The predictable result included accusations of “shoddy service” customers were forced to take or leave. In the handful of markets where TCI faced another cable competitor, TCI ruthlessly slashed prices to levels some would describe as “predatory,” only to rescind them the moment the competitor was gone. TCI’s intolerance for competition usually meant mounting pressure on competitors to sell their system to TCI (sometimes at an astronomical price) or face a certain slow death from unsustainable price cuts.

Among Malone’s most-trusted friends: junk bond financier Michael Milken and Leo Hindery, former CEO of Global Crossing.

Congressman Albert Gore, Jr., later vice-president during the Clinton Administration, was probably Malone’s fiercest critic in Washington. Gore’s office was swamped with complaints from his Tennessee constituents upset over TCI’s constant rate increases and anti-competitive behavior.

The cable industry’s biggest competitor in the 1980s-1990s was a TVRO 6-12 foot diameter home satellite system.

Gore was especially unhappy that TCI’s grip extended even to its biggest competitor — satellite television.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, cable operators made life increasingly difficult for home satellite dish owners, many in rural areas unserved by cable television. But things were worse for home dish owners that walked away from TCI and began watching satellite television instead. To protect against cord-cutting, the cable industry demanded encryption of all basic and premium cable channels delivered via satellite. It was not hard to convince programmers to scramble — most cable networks in the 1980s were part-owned by the cable industry itself.

To make matters worse, unlike cable systems that only leased set-top boxes to customers, home dish owners had to buy combination receiver-descrambler equipment outright, starting at $500. Just a few years later, the industry pressured programmers to switch to a slightly different encryption system — one that required home dish owners replace their expensive set-top box with a different decoder module available only for sale.

Gore was further incensed to learn TCI often insisted home dish owners living within a TCI service area buy their satellite-delivered programming direct from the cable company. Customers hoping to leave cable for good found themselves still being billed by TCI.

Sometimes the rhetoric against TCI and Malone got personal.

”He called me Darth Vader and the leader of the cable Cosa Nostra,” Malone said of Gore. “You can’t win a pissing contest with a skunk, so there’s no point in getting involved in that kind of rhetoric.”

“There’s a joke going around Washington,” John Tinker, a New York-based Morgan Stanley & Company investment banker who specializes in cable television said of Malone back in 1990. “If you have a gun with two bullets, and you have Abu Nidal, Saddam Hussein and John Malone in a room, who would you shoot? The answer is John Malone — twice, to make sure he’s dead.”

TCI itself was a four letter word in the many small communities that endured the cable company’s insufferable service, outdated equipment, and constant rate “adjustments.”

The New York Times reported John Malone’s TCI had a reputation for treating customers with “utter disdain,” and provided examples:

- In 1973, rate negotiations stalled with local regulators in Vail, Colo., the local TCI system shut off all programming for a weekend and ran nothing but the names and home phone numbers of the mayor and city manager. The harried local government gave in.

- In 1981, TCI withheld fees and vowed to go completely dark in Jefferson City, Mo., if the city failed to renew its franchise, while a TCI employee — “who turned out to have a psychological problem,” said Malone — threatened harm to the city’s media consultant. Again, a beleaguered local government renewed the franchise — although in a subsequent lawsuit, TCI was fined $10.8 million in actual damages and $25 million in punitive damages.

- In 1983, the small city of Kearney, Neb., also dissatisfied with poor service and rising rates, tried to give Malone some competition in the form of a rival system built by the regional telephone company. TCI slashed fees and added channels until the enemy was driven from the field.

“That’s the dark side, if you will, of TCI,” said Richard J. MacDonald, a media analyst with New York-based MacDonald Grippo Riely.

By mid-1989, Malone’s frenzied effort to consolidate the cable industry resulted in him presiding over 482 merger/buyout deals, on average one every two weeks. Among the legacy cable companies that no longer existed after TCI’s takeover crew arrived: Heritage Communications, United Artists Communications and Storer Communications.

To cover the debt-laden deals, Malone simply raised cable rates and shopped for easy credit. Bidding with others’ money, the per-subscriber price of cable systems shot up from $998 in 1983 to an astronomical $2,328 in 1989.

The General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, found deregulating the cable industry cost customers through rate hikes averaging 43 percent. In Denver, TCI raised rates more than 70% between 1986 and 1989.

Malone’s attempt to finance a leveraged, debt-heavy buyout of Time Warner Cable seems to show his business philosophy has not changed much.

Subscribe

Subscribe

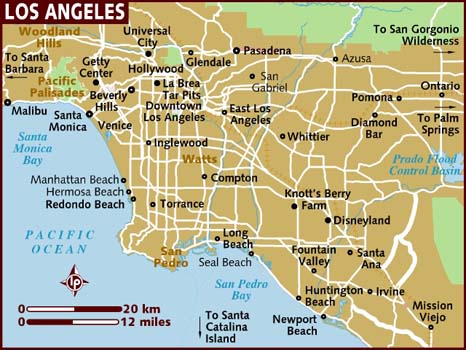

The city can offer some incentives to attract an outsider, such as promising a lucrative contract to manage the city government’s telecom needs. It can also ease bureaucratic red tape that often stalls big city infrastructure projects. But Los Angeles is not exactly prime territory for a fiber build. Its notorious sprawling boundaries encompass 469 square miles, with many residents and businesses in free-standing buildings, not cheaper to serve multi-dwelling units.

The city can offer some incentives to attract an outsider, such as promising a lucrative contract to manage the city government’s telecom needs. It can also ease bureaucratic red tape that often stalls big city infrastructure projects. But Los Angeles is not exactly prime territory for a fiber build. Its notorious sprawling boundaries encompass 469 square miles, with many residents and businesses in free-standing buildings, not cheaper to serve multi-dwelling units. Set-top box-less Time Warner Cable subscribers in parts of New York City will find more than 90 percent of the basic cable lineup missing from their QAM-equipped televisions as the cable company completes a transition away from analog cable television and begins encrypting almost all its digital channels.

Set-top box-less Time Warner Cable subscribers in parts of New York City will find more than 90 percent of the basic cable lineup missing from their QAM-equipped televisions as the cable company completes a transition away from analog cable television and begins encrypting almost all its digital channels. Frontier Communications’ new simplified pricing with no equipment fees or surprise contracts was well-timed for the phone company as it picked up a growing number of disgruntled Comcast and Time Warner Cable customers fed up with increasing modem rental fees.

Frontier Communications’ new simplified pricing with no equipment fees or surprise contracts was well-timed for the phone company as it picked up a growing number of disgruntled Comcast and Time Warner Cable customers fed up with increasing modem rental fees.