Vermont residents want better internet service and protection for universal access to phone service, even if customers have to pay a surcharge on their bill to make sure the traditional landline is still available in 100% of the state.

Vermont residents want better internet service and protection for universal access to phone service, even if customers have to pay a surcharge on their bill to make sure the traditional landline is still available in 100% of the state.

In contrast, some residents complain, Vermont regulators want to make life easier for a telecom industry that wants to abandon universal service, fails to connect rural customers to the internet, and has left major cell phone signal gaps around the state.

In 2017, Vermont commissioned two surveys that asked 400 business and 418 residential customers about their telecommunications services. It was quickly clear from the results that most wanted some changes.

Vermont is a largely rural, small state that presents a difficult business case for many for-profit telecom companies. Verizon Communications sold its landline business in northern New England, including Vermont, to FairPoint Communications in 2007. FairPoint limped along for several years until it declared bankruptcy and was eventually acquired by Consolidated Communications, which still provides telephone service to most of the state.

Many rural areas are not furnished with anything close to the FCC’s definition of broadband (25/3 Mbps). DSL service at speeds hovering around 4 Mbps is still common, especially in areas relying on Verizon’s old copper wire infrastructure.

Comcast dominates cable service in the state, except for a portion of east-central Vermont, which is served by Charter Communications (Spectrum). Getting cable broadband service in rural Vermont remains challenging, as those areas usually fail the Return On Investment test. Still, 85% of respondents said they had internet service available in their home. Vermont’s Department of Public Service (DPS) estimates about 7% of homes in Vermont have no internet provider offering service, with a larger percentage served only by the incumbent phone company.

The majority of residents own cell phones, with Verizon (47.5%) and AT&T (31.8%) dominating market share. Sprint has 0.6% of the market; T-Mobile has a 1.2% share, both largely due to coverage issues. But even with Verizon and AT&T, 40% of respondents said cell phone companies cannot deliver a signal in their homes. As a result, many residents are hanging on to landline service, which is considered more reliable than cell service. Some 40% of those relying on cell phones said they would consider going back to a landline for various reasons.

The majority of residents own cell phones, with Verizon (47.5%) and AT&T (31.8%) dominating market share. Sprint has 0.6% of the market; T-Mobile has a 1.2% share, both largely due to coverage issues. But even with Verizon and AT&T, 40% of respondents said cell phone companies cannot deliver a signal in their homes. As a result, many residents are hanging on to landline service, which is considered more reliable than cell service. Some 40% of those relying on cell phones said they would consider going back to a landline for various reasons.

With the FCC ready to cut support funding for rural landline service, residents were asked if the state should maintain funding to assure continued universal access to landline service. Among respondents, 87.8% thought it was either “very important” or “somewhat important.” The study also found 51% would accept a general statewide rate increase to cover those costs, while 29% preferred rate increases be targeted to rural ratepayers only. About 16% did not like either idea, and 4% liked both.

When asked whether residents would be interested in having a fiber connection in their home, 80% of respondents said “yes,” but 30% were unwilling to pay a higher bill to get it.

Ironically, the state’s most aggressive residential fiber buildouts are run by some of the smallest community-owned internet providers, rural electric or telecom co-ops, and small independent phone companies. What makes these smaller providers different is that they answer to their customers, not shareholders.

Comcast and Charter are the two largest cable companies in Vermont.

Recently, the DPS released a 100+ page final draft of its 2018 Vermont Telecommunications Plan, setting out a vision of where Vermont should be a decade from now, especially regarding rural broadband expansion, pole attachment issues, and cell tower/small cell zoning.

The report acknowledges the state’s own existing rural broadband expansion fund is woefully inadequate. In 2017, the Vermont Universal Service Fund paid out $220,000 to assist ISPs with building out networks to rural areas.

“The amount of money available to the fund pales in comparison to the amount of funding requests that the Department receives, which is generally in the millions of dollars,” the draft report states. “With approximately 20,000 unserved and underserved addresses in Vermont, the Connectivity Initiative cannot make a meaningful dent in the number of underserved locations.”

Much of the report focuses on ideas to lure incumbent providers into volunteering to expand their networks, either through deregulation, pole attachment reform, direct subsidies, or cost sharing arrangements that split the expenses of network extensions between providers, the state, and residents.

A significant weakness in the report covered the forthcoming challenge of upgrading a state like Vermont with 5G wireless service:

Small cell deployment has been attempted along rural routes with very limited success and the national efforts to expand small-cell, distributed-antenna systems, and 5G upgrades have focused on urban areas. The common refrain on 5G is that ‘it’s not coming to rural America.’ 5G should come to rural Vermont and the state should take efforts to improve its reach into rural areas.

A small cell attached to a light pole.

To accomplish this, the report only recommends streamlining the permitting process for new cell towers and small cells. The report says nothing about how the state can make a compelling case to convince providers to spend millions to deploy small cells in rural areas.

Where for-profit providers refuse to provide service, local communities and co-op phone or electric providers often step into the void. But Vermont prohibits municipalities from using tax dollars to fund telecommunications projects, which the law claims was designed to protect communities from investing in ‘unprofitable broadband networks.’

The draft proposal offers a mild recommendation to change the law to allow towns to bond for some capital expenditures on existing or starting networks:

Vermont could use a similar program to help start Communications Union Districts as well as allow towns to invest in existing networks of incumbent providers. Limitations on the authority to bond would need to be put in place. Such limitations should include focusing capital to underserved locations only, limiting the amount (or percentage) of tax payer dollars allowed to be collateralized, and setting technical requirements for the service.

Such restrictions often leave community broadband projects untenable and lacking a sufficient service area or customer base to cover construction and operating expenses. Instead, only the most difficult and costly-to-serve areas would be served. The current law also prevents local communities from making decisions on the local level to meet local needs.

At a public hearing last Tuesday in Montpelier, the report faced immediate criticism from a state legislator and some consumers for being vague and lacking measurable, attainable goals.

“This plan does not appear to move Vermont ahead in a way that enables it to compete effectively,” said state Sen. Mark MacDonald (D-Orange). “It doesn’t seem to be moving forward at the pace we’re capable of.”

Clay Purvis, director of telecommunications and connectivity for the DPS, defended the plan by alluding to how the state intends to establish a cooperative environment for internet service providers and help cut through red tape. But much of those efforts are focused on resolving controversial pole attachment fees and disputes, assuming there are providers fighting to place their competing infrastructure on those utility poles.

Montpelier resident Stephen Whitaker was profoundly underwhelmed by the report.

“There is no plan at all here,” Whitaker said at Tuesday’s public hearing. “There is some new background information from the 2014 version, but there’s no plan there. There is no objective to reach the statutory goals.”

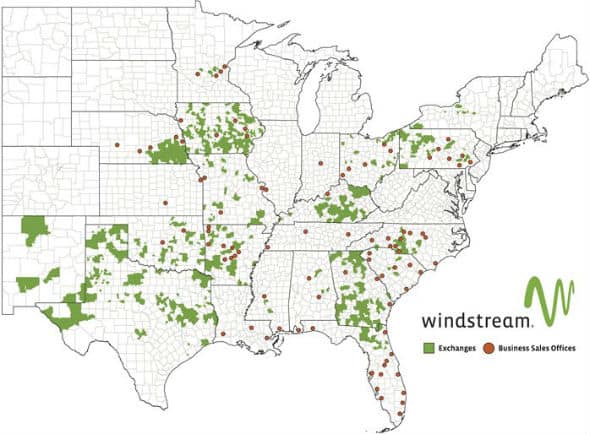

Windstream is relying on the Federal Communications Commission’s Connect America Fund to double the areas where it will offer 100 Mbps broadband service, expected to reach 30% of the company’s 18-state local service area by the end of the first quarter of 2019.

Windstream is relying on the Federal Communications Commission’s Connect America Fund to double the areas where it will offer 100 Mbps broadband service, expected to reach 30% of the company’s 18-state local service area by the end of the first quarter of 2019.

Subscribe

Subscribe A

A  The 101-page filing maintains the FCC overreached by imposing any deal conditions on the 2016 multi-billion dollar merger deal, especially those that might require the merged company to spend money to improve service to customers. CEI argued such conditions were “arbitrary and capricious” and had no place as part of approving a business merger transaction.

The 101-page filing maintains the FCC overreached by imposing any deal conditions on the 2016 multi-billion dollar merger deal, especially those that might require the merged company to spend money to improve service to customers. CEI argued such conditions were “arbitrary and capricious” and had no place as part of approving a business merger transaction.

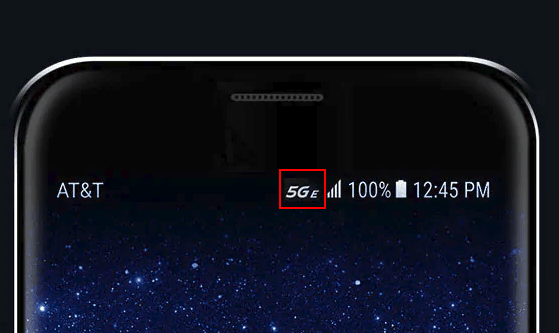

AT&T customers with Samsung Galaxy 8 Active or LG’s V30 or V40 smartphones began noticing a new icon on their phones starting last weekend: an italicized 5G

AT&T customers with Samsung Galaxy 8 Active or LG’s V30 or V40 smartphones began noticing a new icon on their phones starting last weekend: an italicized 5G Walter Piecyk, an analyst at BTIG Research,

Walter Piecyk, an analyst at BTIG Research,

Phone vendors are planning to tamp down customer expectations for their first 5G smartphones, claiming real world speeds will be at or slightly better than 4G LTE speeds in many markets and no better than a few hundred megabits from a barely used cell tower. The 5G technology being deployed to work with smartphones is different from the fixed 5G wireless experience some Verizon customers are getting with its wireless home broadband service.

Phone vendors are planning to tamp down customer expectations for their first 5G smartphones, claiming real world speeds will be at or slightly better than 4G LTE speeds in many markets and no better than a few hundred megabits from a barely used cell tower. The 5G technology being deployed to work with smartphones is different from the fixed 5G wireless experience some Verizon customers are getting with its wireless home broadband service. The latest findings

The latest findings  Vermont residents want better internet service and protection for universal access to phone service, even if customers have to pay a surcharge on their bill to make sure the traditional landline is still available in 100% of the state.

Vermont residents want better internet service and protection for universal access to phone service, even if customers have to pay a surcharge on their bill to make sure the traditional landline is still available in 100% of the state. The majority of residents own cell phones, with Verizon (47.5%) and AT&T (31.8%) dominating market share. Sprint has 0.6% of the market; T-Mobile has a 1.2% share, both largely due to coverage issues. But even with Verizon and AT&T, 40% of respondents said cell phone companies cannot deliver a signal in their homes. As a result, many residents are hanging on to landline service, which is considered more reliable than cell service. Some 40% of those relying on cell phones said they would consider going back to a landline for various reasons.

The majority of residents own cell phones, with Verizon (47.5%) and AT&T (31.8%) dominating market share. Sprint has 0.6% of the market; T-Mobile has a 1.2% share, both largely due to coverage issues. But even with Verizon and AT&T, 40% of respondents said cell phone companies cannot deliver a signal in their homes. As a result, many residents are hanging on to landline service, which is considered more reliable than cell service. Some 40% of those relying on cell phones said they would consider going back to a landline for various reasons.