News that two major cable operators are contemplating breaking up Time Warner Cable and dividing customers between them has caused stock prices to jump for all three of the companies involved.

CNBC reported Friday that Time Warner Cable approached Comcast earlier this year about a possible friendly takeover under Comcast’s banner to avoid an anticipated leveraged takeover bid by Charter Communications. Top Time Warner Cable executives have repeatedly stressed any offer that left a combined company mired in debt would be disadvantageous to Time Warner Cable shareholders, a clear reference to the type of offer Charter is reportedly preparing. But the executives also stressed they were not ruling out any merger or sale opportunities.

News that there were two potential rivals for Time Warner Cable excited investors, particularly when it was revealed possible suitor Comcast is also separately talking to Charter about a possible joint bid that would split up Time Warner Cable customers while minimizing potential regulatory scrutiny.

News that there were two potential rivals for Time Warner Cable excited investors, particularly when it was revealed possible suitor Comcast is also separately talking to Charter about a possible joint bid that would split up Time Warner Cable customers while minimizing potential regulatory scrutiny.

The Wall Street Journal reported Charter is nearing completion of a complicated financing arrangement that some analysts expect could include up to $15 billion in debt to finance a buyout of Time Warner Cable. Such deals are not unprecedented. Dr. John Malone’s specialty is leveraged buyouts, a technique he used extensively in the 1980s and 1990s to buy countless smaller cable operators in a quest to build Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) into the nation’s then-biggest cable operator.

In addition to Barclays Bank, Bank of America, and Deutsche Bank — all expected to finance Malone’s bid — Comcast may also inject cash should it team up with Charter’s buyout. Comcast is interested in acquiring new markets without drawing fire from antitrust regulators.

If the two companies do join forces and pull off a deal, Time Warner Cable’s current subscribers will be transitioned to Charter or Comcast within a year. That is what happened in 2006 to former customers of bankrupt Adelphia Cable who eventually became Comcast or Time Warner Cable customers. Analysts predict the two companies would divide up Time Warner Cable territory according to their respective footprints. New York and Texas would likely face a switch to Comcast service, for example, while North Carolina, Ohio, Maine, and Southern California would likely be turned over to Charter.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/CNBC Comcast Charter consider joint bid for Time Warner Cable 11-22-13.mp4[/flv]

CNBC reports Charter Cable and Comcast might both be interested in a buyout of Time Warner Cable that would dismantle the company and divide subscribers between them. (4:18)

Reportedly financing the next era of cable consolidation.

Both bids are very real possibilities according to Wall Street analysts. Comcast has sought formal guidance on how to deal with the antitrust implications of a controversial merger between the largest and second-largest cable operators in the country. The industry has laid the groundwork for another wave of consolidation by winning its 2009 court challenge of FCC rules limiting the total market share of any single cable operator to 30 percent. Despite that, a Comcast-Time Warner Cable deal would still face intense scrutiny from the Justice Department. Getting the deal past the FCC may be a deal-breaker, admits Craig Moffett from MoffettNathanson.

“The FCC applies a public interest test that would be much more subjective,” Moffett said. “It wouldn’t be a slam dunk by any means. The FCC would be concerned that Comcast would have de facto control over what would be available on television. If a programmer couldn’t cut a deal with Comcast, they wouldn’t exist.”

Roberts

Supporters and opponents of the deal are already lining up. Charter shareholders would likely benefit from a Charter-only buyout so they generally support the deal. Time Warner Cable clearly prefers a deal with Comcast because it can afford a buyout without massive debt financing and deliver shareholder value. Comcast shareholders are also encouraging Comcast to consider s deal with Time Warner Cable. Left out of the equation are Time Warner Cable customers, little more than passive bystanders watching the multi-billion dollar drama.

The personalities involved may also be worth considering, because Comcast CEO Brian Roberts and John Malone have history, notes the Los Angeles Times:

Malone and Roberts first brushed up against each other more than two decades ago. At that time, both Liberty and Comcast were shareholders in Turner Broadcasting, the parent of CNN, TNT, TBS and Cartoon Network. When Time Warner, which was also a shareholder, made a move to buy the entire company, there was tension because Comcast felt Liberty got a better deal to sell its stake. Roberts grumbled at the time that Liberty was getting “preferential treatment.”

A few years later, it was Malone’s turn to be mad at Roberts. When TCI founder Bob Magness died in 1996, Roberts made a covert attempt to buy his shares, which would have given him control of [TCI]. Malone beat back the effort, but it left a bad taste in his mouth.

“Malone was livid,” wrote Mark Robichaux in his book, “Cable Cowboy: John Malone and the Rise of the Modern Cable Business.”

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/CNBC Comcast seeks anti-trust advice over TWC deal 11-22-13.mp4[/flv]

Even cable stock analyst Craig Moffett is somewhat pessimistic a Comcast-TWC merger would have smooth sailing through the FCC’s approval process. Moffett worries Comcast would have too much power over programming content. (3:53)

Ironically, when Malone sold TCI to AT&T, the telephone company would later sell its cable assets to Comcast, run by… and Brian Roberts.

Ironically, when Malone sold TCI to AT&T, the telephone company would later sell its cable assets to Comcast, run by… and Brian Roberts.

Most of the cable industry agrees that the increasing power of broadcasters, studios, and cable programmers is behind the renewed interest in cable consolidation. The industry believes consolidation provides leverage to block massive rate increases in renewal contracts. If a programmer doesn’t budge, the network could instantly lose tens of millions of potential viewers until a new contract is signed.

Many in the cable industry suspect when Glenn Britt retires as CEO by year’s end, Time Warner Cable’s days are numbered. But any new owner should not expect guaranteed smooth sailing.

“We expect a Comcast-TWC deal would draw intense antitrust/regulatory scrutiny and likely resistance, stoked by raw political pushback from cable critics and possibly rivals who would argue it’s simply a ‘bridge too far’ or ‘unthinkable,’” Stifel telecom analysts Christopher C. King and David Kaut wrote in a recent note to clients. “We believe government approval would be possible, but it would be costly, with serious risk. This would be a brawl.”

Usage Cap Man may soon visit Time Warner Cable customers if either Charter or Comcast becomes the new owner.

While the industry frames consolidation around cable TV programming costs, broadband consumers also face an impact from any demise of Time Warner Cable. To date, Time Warner Cable executives have repeatedly defended the presence of an unlimited use tier for its residential broadband customers. Charter has imposed usage caps and Comcast is studying how to best reimpose them. Either buyer would likely move Time Warner Cable customers to a usage-based billing system that could threaten online video competition.

“Our sense is the DOJ and FCC would have concerns about the market fallout of expanded cable concentration and vertical integration, in a broadband world where cable appears to have the upper hand over wireline telcos in most of the country (i.e., outside of the Verizon FiOS and other fiber-fed areas),” Stifel’s King and Kaut wrote. “We suspect the government would raise objections about the potential for Comcast-TWC bullying of competitors and suppliers, given the extent and linkages of their cable/broadband distribution, programming control, and broadcast ownership.”

Since none of the three providers compete head-on, the loss of “competition” would be minimal. Any Comcast-Time Warner Cable deal would likely include semi-voluntary restrictions like those attached to Comcast’s successful acquisition of NBC-Universal, including short-term bans on discriminating against content providers on its broadband service.

Customers can expect a welcome letter from Comcast and/or Charter Cable as early as spring of next year if Time Warner Cable accepts one of the deals.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg Comcast and Charter Reportedly Weighing Bid for TWC 11-22-13.flv[/flv]

Bloomberg News reports if Comcast helps finance a deal between Charter and Time Warner Cable, Comcast would likely grab Time Warner Cable systems in New York for itself. (2:26)

Subscribe

Subscribe

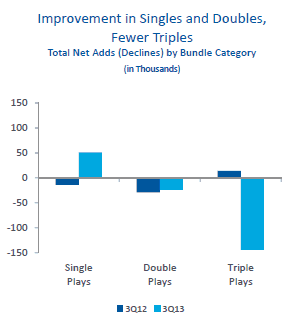

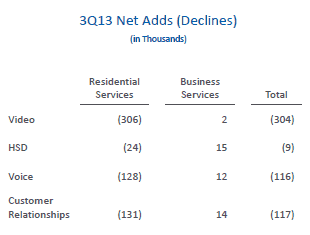

Time Warner Cable’s summer was “horrible,” to quote one analyst, after three percent of customers left over programming disputes and increasing prices for broadband and telephone service, with more likely to follow as price promotions expire and rates increase further.

Time Warner Cable’s summer was “horrible,” to quote one analyst, after three percent of customers left over programming disputes and increasing prices for broadband and telephone service, with more likely to follow as price promotions expire and rates increase further.

AT&T and Verizon are among the biggest tech company spenders in Washington, paying millions every quarter to lobby federal and state lawmakers on how they can make life easier for the telecom giants.

AT&T and Verizon are among the biggest tech company spenders in Washington, paying millions every quarter to lobby federal and state lawmakers on how they can make life easier for the telecom giants.

With LightSquared’s debt trading at around 50 cents on the dollar, Charlie Ergen went shopping.

With LightSquared’s debt trading at around 50 cents on the dollar, Charlie Ergen went shopping.