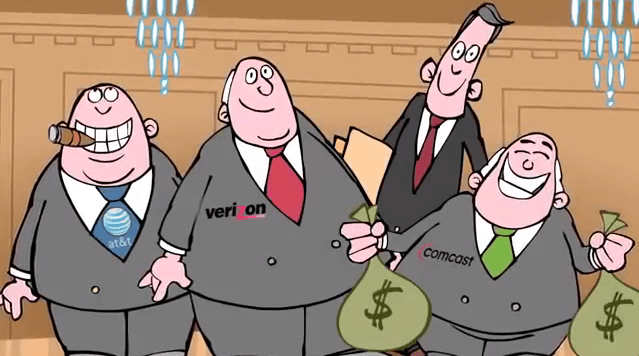

When the multibillion dollar telecom industry wants to push its narrative about telecom public policy, it employs an army of secretly funded astroturf groups, corporate-backed “policy institutes,” professional lobbyists, and ex-regulators and politicians that help move their agenda forward.

When the multibillion dollar telecom industry wants to push its narrative about telecom public policy, it employs an army of secretly funded astroturf groups, corporate-backed “policy institutes,” professional lobbyists, and ex-regulators and politicians that help move their agenda forward.

One of the latest methods to win influence is finding researchers willing to produce scholarly reports offering “independent” analyses of regulatory policies or telecom company business practices. It has now become a cottage industry, with the same select few authors regularly writing papers that align perfectly with the interests of cable and telephone companies that sponsor the groups, think tanks, or schools that employ them.

The blurred line between academic independence and “research-for-hire” has become increasingly indefensible at the nation’s think tanks, where politically motivated individuals and corporate donors funnel millions in funding with the expectation the think tank, its leadership and researchers will fall in line with the political views of the donor and act accordingly. When they don’t, the checks stop coming or a donor-led coup d’état similar to what happened in April at the Heritage Foundation can follow.

The idea that a think tank represents an independent body of researchers tackling random issues of the day without bias is quaint and often a thing of the past. These days, some think tanks and policy institutes dependent on corporate and big donor contributions are little more than willing corporate tools in policy and regulatory debates. Last month, this reached a new level of absurdity with the announcement that the MGM Resorts — a Las Vegas casino, was starting its own policy institute co-chaired by retired Sen. Harry Reid and former House Speaker John Boehner. Neither will be working for free. The stated purpose of the MGM think tank is to “concentrate on comprehensive, authentic and relevant national and international policy issues that impact the travel, tourism, hospitality and gaming industries and the global communities in which they operate.”

In short, it’s another way for the casino industry to lobby while operating under a veneer of independence at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

If a researcher cannot find work at a policy institute or think tank, they can always produce research papers under the auspices of a university or business school that welcomes corporate funding. These institutions assume they are protecting their credibility and reputation with claims of a firewall between industry money and research, yet too often the reports that result from this arrangement are embarrassingly industry-aligned. Questions of conflict of interest are also increasingly common when a researcher turns up at hearings to deliver ostensibly independent testimony on issues like regulation or their views about multi-billion dollar mergers and acquisitions that are in perfect alignment with the companies that donate to that researcher’s employer.

Researchers like Christopher Yoo at the University of Pennsylvania Law School in Philadelphia bristle at the notion corporate dollars play any role in his research or findings, despite the fact he was accused of a major conflict of interest testifying strongly in favor of Comcast’s attempted merger with Time Warner Cable in 2014. Yoo defended the Comcast deal at every turn, telling Congress the merger would have little impact on consumer prices or competition, despite the fact ample antitrust concerns ultimately torpedoed the deal.

Yoo avoided disclosing the fact he had ties to Comcast’s chief lobbyist David Cohen, who sat five seats to his right at the hearing. Cohen served as chairman of the board of trustees at the University of Pennsylvania and Comcast is an extremely generous financial donor of the university — two obvious conflicts of interest that observers expressed shock were not disclosed in advance. Yoo focused instead on delivering testimony we characterized back in 2014 as “a nod in Cohen’s direction with an affirming, ‘whatever he said.'”

When the media called him out on the subject, Yoo downplayed any connection or conflict.

“The views of any other person in the university administration do not have any impact on my academic views or any public statements I make,” Yoo told the Washington Post. He added the Center for Technology, Innovation, and Competition that he founded was only “a tiny little bit” funded by the cable industry. We’ll fact check that claim shortly.

Like Harry Reid and John Boehner, Christopher Yoo does not work for free. Despite his claims that as a tenured professor, his academic freedom is protected, Mr. Yoo’s recent written work has been so closely aligned with the interests of the nation’s cable and phone companies, he comes alarmingly close to being an academic version of a corporate sock puppet.

Yoo is hardly the only researcher that has an amazing record of producing studies that coincidentally line up in perfect unison with the public policy interests of giant cable companies. Daniel Lyons of Boston College Law School prodigiously writes papers defending the cable industry’s practice of data caps. He’s been hard at work since 2012 trying to convince anyone that would listen that data caps are good for consumers, competition, and innovation. Like Yoo, Lyons was also a big supporter of Comcast’s attempted purchase of Time Warner Cable, “spontaneously” and “independently” penning long letters to the editor to newspapers all around the country defending the deal.

So what causes researchers to suddenly decide to write about some topics but not others? Random chance or money?

Last month, Yoo unveiled his latest paper, “Municipal Fiber in the United States: An Empirical Assessment of Financial Performance,” co-authored by Timothy Pfenninger.

Last month, Yoo unveiled his latest paper, “Municipal Fiber in the United States: An Empirical Assessment of Financial Performance,” co-authored by Timothy Pfenninger.

Yoo claimed in his executive summary that the “current emphasis on infrastructure projects in the United States has intensified the debate over municipal broadband.” That’s news to us. In fact, the high water mark of the municipal broadband debate occurred in the last administration when FCC Chairman Thomas Wheeler sought to nullify corporate ghostwritten municipal broadband bans passed by several state legislatures.

Yoo decided he would be a “helper” for cities contemplating repeating the success of EPB, the municipal power company in Chattanooga, Tenn., that built a successful public gigabit fiber to the home broadband network for the city and nearby communities. The “widespread news coverage” of EPB that Yoo wrote about, without mentioning it was almost exclusively positive, has apparently inspired a number of other communities to contemplate repeating Chattanooga’s success story.

In what we like to call Yoo’s “Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt” opening, he warns “city leaders who turn to existing municipal fiber analyses for guidance will discover that these studies limit their focus to the supposed success stories instead of systematically analyzing these systems’ financial performance.”

So instead of those studies, Yoo offers his own, which he claims “fills the information gap” by creating a whole new systematic analysis, using Yoo’s own hand-crafted criteria, to judge the success or failure of municipal broadband.

He doesn’t waste any time hinting municipal broadband is a bad idea, puts cities at risk for defaults, bond rating reductions, and taxpayer bailouts. In fact, Yoo characterized municipal broadband as a mere distraction from more important priorities he claims communities have. And besides, there is evidence showing “little current need for [the] high broadband speeds” that community broadband networks offer that incumbent cable and phone companies won’t.

Yoo’s take is like bringing a boyfriend home to your parents who claim they support and love you no matter who you date but then spend the next two hours telling you why he’s all wrong for you.

Follow the Money

We thought it would be useful to look into Yoo’s claims and conclusions more carefully. As always, we focused on two things: fact-checking the evidence and following the money.

We thought it would be useful to look into Yoo’s claims and conclusions more carefully. As always, we focused on two things: fact-checking the evidence and following the money.

It took very little time to turn up more red flags than one would find at a May Day parade in Red Square.

Academics with conflicts of interest or uncomfortably close ties to the telecom industry and the reports they peddle often escape scrutiny, because their research can intimidate journalists unprepared to challenge their premise, research, or conclusions without a substantial investment of time and fact-checking. But as we’ve learned over the years, there are very clear warning signs when more investigation is necessary.

We’re not alone. This week National Public Radio updated its Ethics Handbook with “a cautionary tip sheet about relying on the work product of think tanks.”

It is “our job to know about ‘experts’ conflicts of interest” and share that information with our audience (or not use experts whose conflicts are problematic). As we’ve said, it’s not optional. Click here for related reading from JournalistsResource.org. It includes “some questions journalists should ask when researching think tanks.” Among them:

- “Look at the think tank’s annual report. Who is on staff? On the board or advisory council? Search for these people. They have power over the think tank’s agenda; do they have conflicts of interest? Use OpenSecrets’ lobby search, a project of the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics, to see if any of these individuals are registered lobbyists and for whom.

- “Does the organization focus on one issue alone? If so, look carefully at its funding.

- “Does the organization clearly identify its political leanings or its neutrality?

- “Does the annual report list donors and amounts? Are large donors anonymous? If the answer to the second question is yes, you should be concerned that big donors may be trying to hide their influence.

- “Does it have a conflict of interest policy?”

The Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy is even more frank in its warning to journalists who rely on think tanks and industry-based research:

[…] Entrenched conflicts of interest across the political spectrum, and pandering to donors, often raise questions about their independence and integrity. A few years ago, think tanks were seen as places for wonky scholars and former officials to bang out solutions to critical policy problems. But today, as the Boston Globe has written, many “are pursuing fiercely partisan agendas and are funded by undisclosed corporations, wealthy individuals, or both.”

Unsurprisingly, Yoo’s research was immediately distributed and promoted by a range of groups critical of public broadband to build what they believe to be an authoritative record against municipal broadband initiatives. In effect, ‘it isn’t just us saying public broadband is a bad idea, look at this ”independent” research.’

But exactly how independent is the research produced by Mr. Yoo and his Center for Technology, Innovation and Competition (CTIC)? Unfortunately, Yoo does not follow the common practice of disclosing the funding sources for his research and report. If it was funded through the Center, that should be disclosed. If a corporate donor provided funding or a stipend, that should be disclosed. If part or all of Mr. Yoo’s compensation comes from a bank account replenished in part or whole by an outside company, that should be disclosed. If he wrote the report in this spare time for fun, that should be disclosed as well.

Since Mr. Yoo doesn’t talk about the money, we will.

The CTIC’s website spends some time predicting the obvious conflicts of interest questions raised by its extensive corporate donor base.

“The Center for Technology, Innovation & Competition (CTIC) receives financial support from corporations, foundations, and other organizations that is vital to our continued growth and success,” the website states, which means without that support, there probably would be no CTIC.

Which corporations donate money is important to consider. If a substantial amount of a researcher’s funding comes from telecom companies that are either on record opposing public broadband, or would be forced to compete with a municipal broadband provider, that would represent a very clear conflict of interest.

CTIC attempts to inoculate itself from accusations it has that inherent conflict of interest with this statement on its website:

“CTIC does not accept financial support that limits our ability to conduct independent research. This allows us to produce scholarship that is free from outside influence and consistent with Penn’s ethics and values. All corporate donors agree to provide funding free from restrictions and promised results or deliverables.”

But that is not adequate enough to protect readers from researcher bias introduced by the donor funding that CTIC admits is “vital” to their existence. Consider the example of the tobacco industry, one of the first to leverage researchers willing to write papers created to distort, downplay, or confuse the debate about the safety of tobacco products. There was no need for a tobacco company to limit researcher independence or demand a certain result. That allowed researchers to claim editorial independence, but they also understood that if their reports did not meet the expectations of the tobacco company that paid for them, they would never be made public and that researcher would never be used again.

But that is not adequate enough to protect readers from researcher bias introduced by the donor funding that CTIC admits is “vital” to their existence. Consider the example of the tobacco industry, one of the first to leverage researchers willing to write papers created to distort, downplay, or confuse the debate about the safety of tobacco products. There was no need for a tobacco company to limit researcher independence or demand a certain result. That allowed researchers to claim editorial independence, but they also understood that if their reports did not meet the expectations of the tobacco company that paid for them, they would never be made public and that researcher would never be used again.

A corporate donor is unlikely to continue funding an organization that issues reports it disagrees with or worse, publicly bolsters its competitors or criticizes its public policy agenda. Had Yoo concluded municipal broadband was an ideal solution for the rural broadband, internet speed, and competition problems in this country would AT&T, CTIA, Comcast, Charter/Time Warner Cable, NCTA and Verizon still send them checks?

While considering the veracity of Mr. Yoo’s research and conclusions, do you believe CTIC’s donors would be pleased or unhappy about the report? Here is the list of companies and groups that help keep the lights on at CTIC:

American Tower (owns cellular and broadcast transmission towers)

American Tower (owns cellular and broadcast transmission towers)- AT&T

- Broadband for America (funded by the cable/telco industry)

- Cellular Operators Association of India

- Comcast-NBC Universal

- CTIA (the cellular industry’s top lobbying trade association)

- GSMA (Mobile industry trade association)

- ICANN

- Information Technology Industry Council

Intel

Intel- Internet Society

- Microsoft

- National Science Foundation

- NCTA (cable industry’s top lobbying group)

- New York Bar Foundation

- Qualcomm

- Time Warner Cable (now Charter Communications)

- Verizon

- Walt Disney Co.

It’s clear there are few friends of municipal broadband donating to the CTIC while we count about eight likely opponents.

Even the way Mr. Yoo introduced his municipal broadband report at a Wharton Business School “broadband breakfast discussion” opened the door to more questions. To suggest the panel was stacked against public broadband would be an understatement.

In addition to Mr. Yoo, the former mayor of Philadelphia and governor of Pennsylvania Ed Rendell — who was hired by Comcast-NBC Universal less than two months after coming out in strong support of the merger of Comcast and NBC-Universal, was tasked with keynote remarks. Joining both on the discussion panel was Frank Louthan, a Wall Street analyst for Raymond James who regularly covers big cable and telco companies for investors and wouldn’t appreciate giving the bad news to clients about municipal broadband’s profit-killing competition and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the corporate dark money-backed American Action Forum who seemed enamored of all-things Comcast. In 2014, Holtz-Eakin went out of his way to write a long piece urging regulators to approve the Comcast-Time Warner Cable acquisition as soon as possible.

Anyone who wanted to hear a positive view of municipal broadband would have had to eat breakfast somewhere else.

Yoo’s “Evidence”

For the benefit of readers and local officials that want a more detailed refutation of Mr. Yoo’s study and his findings on the granular level, we point you to Community Broadband Networks’ excellent report debunking the obviously biased findings from Mr. Yoo, who appears to be working on behalf of some of America’s largest telecom companies. Mr. Yoo will claim those companies did not sponsor the study, but we remind readers that without the extensive donor support of Yoo’s group from the telecom industry, there would likely be no study.

But we found several red flags to share as well.

Red Flag #1: Changing the metrics.

Red Flag #1: Changing the metrics.

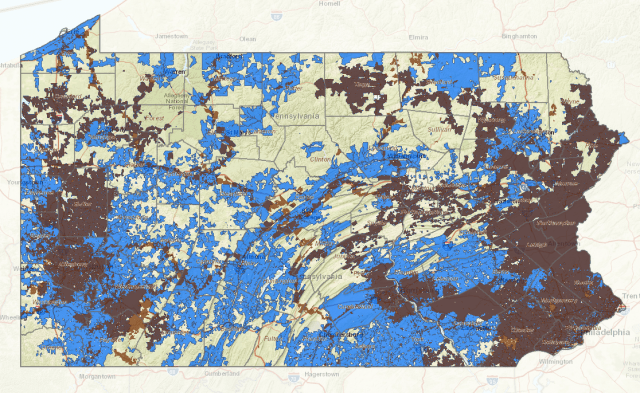

Mr. Yoo hand-selects the metrics by which municipal network success or failure can be determined… by him. He relies on Net Present Value, a particularly complicated and not always accurate measurement of a network’s prospects for success or failure. Clearly, every municipal network will face some challenges. Many are in areas deemed unprofitable to serve by the commercial telecom industry. But then, municipal broadband is all about solving the problem of broadband accessibility that other ISPs won’t. These public networks don’t exist to make shareholders and executives rich, nor do they have to allocate money to pay shareholder dividends. Even commercial ISPs have their hands out looking for subsidies to wire rural areas they would otherwise never serve. There is more to the story of municipal broadband than profit and loss.

Red Flag #2: Financing concrete.

Red Flag #2: Financing concrete.

Mr. Yoo’s predictions that some networks may never pay off their debts or will take dozens of years or more doing so assumes almost nothing changes for those networks in the near or distant future. Broadband networks are constantly evolving, as are potential revenue sources. Imagine a cable company having to exclusively rely on cable TV revenue to pay down their debt. Then remember the day cable operators discovered they could use a portion of their existing network to sell something called “broadband” service for another $30 a month. Ancillary revenue from the introduction of innovative new products and services is precisely how the cable industry successfully boosted subscriber revenue even in mature markets where adding new customers was challenging. They followed the time-tested principle of selling more things to the customers they already have.

But then Mr. Yoo agreed with this concept himself… when he was talking about the some of the same telecom companies that write his group checks. Municipal networks are somehow… different, however:

The development of the Internet has greatly increased the value of the services that can be provided by last-mile networks. The rollout of convergent technologies, such as Internet telephony and packet video, will break down the barriers that previously limited the revenues generated by any particular transmission technology. Cable is already able to provide voice through its coaxial network, and it is just a matter of time before telephone companies are able to provide video. Application-based distinctions between transmission media will completely collapse once all applications become packetized.

He also downplays the tool of refinancing. Altice turns that concept into a weekend hobby. This European cable conglomerate’s business plan leverages debt like no other cable operator. It manages that debt by regularly repackaging and refinancing debt at lower rates as it also works to pay it down. These same options are available to municipal providers.

Red Flag #3: Municipal broadband is too expensive, or is it?

Red Flag #3: Municipal broadband is too expensive, or is it?

There are massive start-up costs to build broadband networks, costs that might put a community’s finances at risk, Yoo’s report concludes. That leaves the obvious impression communities should avoid going there. But that wasn’t the attitude he had in 2006, when network costs were even higher than they are today.

“The economics of the last mile have changed radically in recent years,” Yoo said. “The fixed costs of establishing last-mile networks have dropped through the floor. Switching equipment that used to take up an entire building can now be housed in a box roughly the size of a personal computer. Copper wires have been replaced by a series of innovations, including terrestrial microwave, satellites, and fiber optics, which have greatly reduced the costs of transmission.”

When he is talking about municipal broadband, he seems to tell an entirely different story. Why might that be?

Red Flag #4: Yoo misrepresents the problem.

Red Flag #4: Yoo misrepresents the problem.

Mr. Yoo has reflexively defended his donor base for several years across a myriad of broadband public policy issues — data caps/zero rating, Net Neutrality, mergers and acquisitions, network costs, and more. The hypocrisy emerges when his entirely different standards for municipal broadband become clear.

The toll from “personal turmoil and distraction” Yoo worries about with municipal broadband projects ignores the real problem — the lack of suitable broadband in a community with no solution in sight. Just ask families that drive their kids to a fast food restaurant to borrow a Wi-Fi connection to complete homework assignments, or the difficulty getting broadband in a neighborhood bypassed by DSL or cable. If a community defines broadband as an essential utility, it provides it even if it doesn’t turn a profit. Public infrastructure projects are not unusual. The amount of money spent by an industry worried about losing its duopoly or monopoly profits to oppose such projects could have been spent on improving and expanding service.

If a local community wants a municipal solution, it is Mr. Yoo’s donors that create most of the turmoil by ghostwriting municipal broadband bans into state law and filing groundless stall tactic lawsuits designed to protect their markets or run up costs.

Red Flag #5: There is “little current need” for high broadband speed (unless Comcast offers it).

Red Flag #5: There is “little current need” for high broadband speed (unless Comcast offers it).

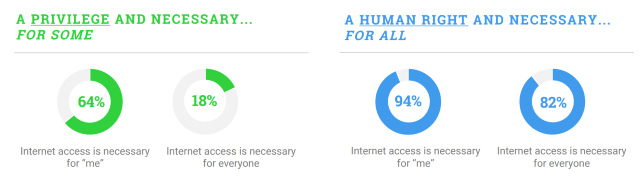

One of the best clues that Mr. Yoo’s research isn’t as “independent” as he implies is the fact his conclusions seem to change depending on whether he is referring to a corporate ISP or a municipal provider. For example, Yoo’s study downplays the importance of gigabit fiber speeds. In one highlighted statement, Yoo declares, “The U.S. take-up rate of gigabit service remains very low, and media outlets report that consumers are questioning if gigabit service is really necessary.”

“The media” in this case is Multichannel News, a cable industry trade publication that has changed its tune about that subject recently and now publishes stories regularly about ISPs across the country moving towards gigabit speeds. In the article noted by Yoo, the story quotes a single CenturyLink executive who claims customers can live with the slower speeds CenturyLink often provides, but also admits his company is working to deploy, wait for it, gigabit-capable networks. As Stop the Cap! has explained to readers for a decade, the companies that always claim consumers don’t need a gigabit are the same ones that do not offer it to a large percentage (or any) of their customers. Yoo fails to explain why so many ISPs are preoccupied with offering fast internet speeds that he declares are unwanted, especially when a municipal provider plans to offer them.

Yoo’s allegiance to the current big cable and phone company provider paradigm is revealed when you scrutinize his reasons why community fiber is unnecessary. Take this example from his report:

“Wireless technologies—such as 5G—and legacy copper technologies—such as G.fast—are also exploring ways to provide gigabit speeds without incurring the cost associated with FTTH.”

“Exploring” is very different from “delivering.” Let’s also not forget he held a very different view when he wasn’t slamming municipal broadband:

“On the one hand, the Bell System created a telephone network that was the envy of the world and pioneered Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs such as the transistor. On the other hand, it was extremely slow to deploy innovative technologies like DSL.”

It’s also important to note a large percentage of community broadband networks are based on fiber optics while commercial wireless companies like AT&T and Verizon are among the few willing to deploy 5G and incumbent telephone companies show only limited interest in G.fast.

And again, Yoo should take a bit of his own advice on picking or discouraging technology or municipal broadband provider winners and losers:

“At this point, it is impossible to foresee which architecture will ultimately represent the best approach. When it is impossible to tell whether a practice would promote or hinder competition, the accepted policy response is to permit the practice to go forward until actual harm to consumers can be proven. This restraint provides the room for experimentation upon which normal competitive processes depend. It also shows appropriate humility about our ability to predict the technological future.”

Red Flag #6: Innovation is in the eye of the beholder. (Subject to change on a whim).

Red Flag #6: Innovation is in the eye of the beholder. (Subject to change on a whim).

Yoo also distorts a 2014 New York Times article by focusing on the lack of applications available to take advantage of gigabit speeds. But he ignores the fact that customers and entrepreneurs are delighted that speed is available, and offers the potential of significant innovation including very high quality video and enough bandwidth to power the explosion of connected devices in the home. Every major ISP in the country reports consumers are upgrading to faster internet packages, and some customers remain dissatisfied those speeds are still not fast enough.

Again, Yoo is suspiciously inconsistent. When major ISPs sought permission to develop faster traffic lanes for brand new services, Yoo was one of the biggest supporters of the innovation opportunities of that concept:

He hopes that the FCC’s easing restrictions on broadband providers’ ability to charge different prices for delivering different Internet content could spur innovation by allowing both established companies and startups to offer new online services tailored for the Internet “fast lane” delivery. For instance, Yoo pointed to the differentiation between standard U.S. first class postal service with overnight FedEx mail and noted how new businesses have grown around the overnight delivery option.

Apparently the distinction is that companies like Comcast have to be the mail carrier for that to be any good. If a community does it, that means it is unwanted, unnecessary, and bad.

We could go on and on, but we assume most readers get the point. Fixing facts around a narrative has been a part of the telecom industry’s cynical lobbying for decades. Let’s face facts. Yoo’s donors don’t want the competition and don’t want to be forced to invest in upgrades they should have completed long ago. Yoo’s report is part of the campaign to stop municipal broadband before it gets off the ground.

Where did we learn this? From Yoo himself, who wrote the best way to improve broadband is remove barriers that keep new providers, including municipal ones if he wants to be consistent, from launching service:

“Competition policy thus teaches us that any vertical chain of production will only be as efficient as its least competitive link. The proper focus of broadband policy is to identify the level of production that is the most concentrated and the most protected by entry barriers and to try to make it more competitive.”

“Furthermore, large, established players have more resources and experience with which to influence the regulatory process.”

Those are two things we can agree on.

Subscribe

Subscribe