Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski last week wrote a guest editorial on TechCrunch espousing the benefits of faster broadband networks, but the advances he celebrates often come with innovation-killing usage caps and overlimit fees he continues to ignore.

We feel the need – the need for speed. As Tom Friedman and others have written, in this flat global economy a strategic bandwidth advantage will help keep the U.S. as the home and most desired destination for the world’s greatest innovators and entrepreneurs.

[…] But progress isn’t victory, particularly in this fast-moving sector. Challenges to U.S. leadership are real. This is a time to press harder on the gas pedal, not let up. The first challenge is the need for faster and more accessible broadband networks. We need to keep pushing because our global competitors aren’t slowing down. I’ve met with senior government officials and business leaders from every continent, and every one of them is focused on the broadband opportunity. If we in the U.S. don’t foster major investments to extend and expand our broadband infrastructure, somebody else will take the lead.

We need to keep pushing because innovators need next-generation bandwidth for next-generation innovations – genetic sequencing for cancer patients, immersive and creative software to help children learn, ways for small businesses to take advantage of Big Data, and speed- and capacity-heavy innovations we can’t yet imagine.

We need to remove bandwidth as a constraint on our innovators and entrepreneurs. In addition to steadily increasing broadband speed and capacity for consumers and businesses throughout the country, we need – as we said in our National Broadband Plan – “innovation hubs” with super-fast broadband, with speed measured in gigabits, not megabits.

[…]Some argue the private sector will solve these challenges itself, and that all government has to do is get out of the way. I disagree. The private sector must take the lead, but the public sector has a vital though limited role to play.

Among the policy levers government needs to use is the removal of barriers to broadband buildout, lowering the costs of infrastructure deployment with new policies like “Dig Once” that says you should lay fiber when you dig up roads. The President recently issued an Executive Order implementing this idea, suggested in our Broadband Plan. Government must promote competition, which drives innovation and network upgrades.

We must ensure the Internet remains an open platform that continues to enable innovation without permission.

Genachowski’s vision for faster broadband has the noble goal of maintaining competitiveness with the rest of the world and putting the United States back on top in broadband rankings and innovation. But while hobnobbing with his industry friends at recent industry conventions, he may have gotten too close to one of the biggest impediments holding us back — big cable and phone companies merrily working their magic to create a comfortable duopoly with pricing and service plans to match.

Back in the late 1990s, most cable operators thought of broadband as an ancillary service easy enough to operate, but probably hard to monetize. Just like digital cable radio services like Music Choice and DMX, “broadband” would likely appeal only to a tiny subset of customers.

“Back in the 1990s, Time Warner was primarily a TV company in a TV industry. Broadband then was an innovating and radical thing, and a lot of people thought it was stupid and wouldn’t work,” Time Warner Cable CEO Glenn Britt said in April, 2009.

The launch of “Road Runner” was not the most auspicious marketing effort undertaken by the cable operator. In fact, the service was rarely targeted for price adjustments, hovering at around $40 a month for a decade.

When the Great Recession hit the United States, something unexpected happened. Cable operators discovered people were willing to cancel their cable and phone services, but not their broadband. In fact, as high bandwidth online video became an increasing part of our lives, the cable industry realized they were in the catbird seat to deliver the best broadband experience, and be well-paid for it. With little competition, increasing prices brought little risk and, thanks to the insatiable drive to boost revenue and reduce costs, implementing usage caps to control “excess” usage and costs were within their grasp.

In 2008, when Stop the Cap! launched, only a handful of ISPs had usage caps. Now most providers, with the exception of Time Warner Cable, Verizon, Cablevision, and a handful of others, all have usage allowances and overlimit fee Internet Overcharging schemes to further pad their bottom lines.

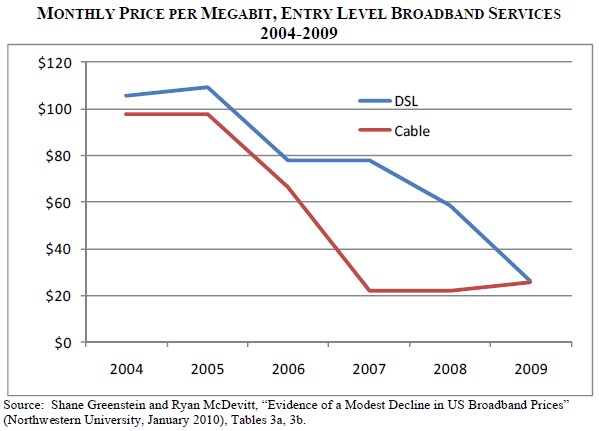

Genachowski has completely ignored the growing pervasiveness of usage caps, and even excused them as an experiment in marketplace innovation. But limits on broadband usage will also limit the broadband innovation revolution he wants, especially when most Americans have just one or two realistic choices for broadband service:

- Usage caps are the product of artificial scarcity. Rationing Internet usage, even with now-pervasive cost-effective upgrades like DOCSIS 3, simply does not make sense (but it will make dollars). Cable operators are switching off analog television service to free up bandwidth to provider faster Internet speed and fatten the pipeline that delivers it. They have plenty of capacity, but continue to proclaim they must limit usage for “fairness” reasons, without providing a single shred of evidence to prove the need for usage caps. Consumers will self-ration just to avoid the prospect of being cut off or handed a bill with overlimit fees.

- Usage caps make faster speeds irrelevant. Selling customers premium-priced, super fast broadband speed is hardly compelling when accompanied by usage caps that constrain the benefits of buying. Why pay $20-50 more for faster speeds when customers cannot take practical advantage of them. Customers using their Internet service to browse web pages and read e-mail have no interest in upgrading to 30+Mbps. Customers streaming video or moving large files do.

- Usage caps retard innovation. Google’s new 1Gbps fiber optic network was built on the premise that usage caps were unnecessary on a fiber-based network and would retard innovation. Developing the next generation of innovative apps that Genachowski celebrates will never happen if developers are discouraged by Internet usage toll booths and stop signs. The cost to provide the service is not largely dependent on customer usage. It is the initial price of last mile infrastructure that really matters. Both cable and phone companies have reduced their investments to upgrade their networks, and AT&T and Verizon both contemplate getting rid of their rural landlines. Most cable operators paid off their networks years ago.

- Usage caps create a whole new digital divide. Time Warner Cable’s discounted Internet Essentials program delivers only a $5 discount with a harsh 5GB usage cap. For an income-challenged home compelled to switch to a provider’s budget plan, the result is a different Internet experience than the rest of us enjoy. Imagine if your home broadband account was limited to 5GB a month. What online services would you have to avoid to stay under the provider’s limit? Traditionally, operators sell the lowest speed tiers with the lowest usage allowances. Slower speeds already offer a disincentive to use high bandwidth services, but many providers typically drive that disincentive home even harder with a paltry allowance that will cost plenty to exceed.

- Usage caps harm our broadband standing. While Genachowski celebrates increasing broadband speeds, he ignores the fact the rest of the world is moving away from usage caps even as the United States moves towards them. Both Australia and New Zealand elected to construct their own national fiber networks in large part because the heavily usage-capped experience was holding both countries back. Usage caps are a product of a barely competitive market.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bandwidth Caps 7-2011.flv[/flv]

Tech News Today debunks providers’ claims that usage caps are fair and control those who “overuse” their networks, noting the same phone companies (AT&T) pushing for usage caps are also moving voice calling to unlimited service plans. (August, 2011) (4 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe