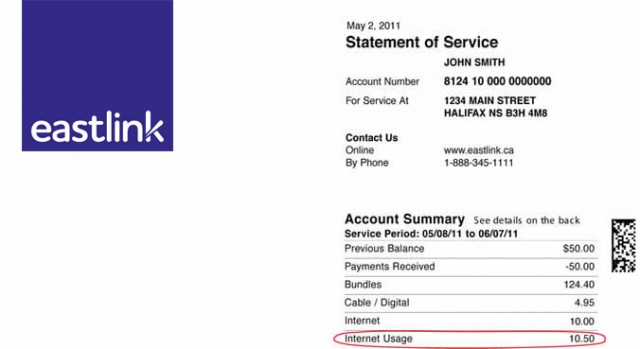

Atlantic Canada provider Eastlink still offer unlimited access for speeds of 20Mbps or slower, but the fastest speeds now come with usage caps and overlimit fees, as depicted on this sample invoice.

While broadband pricing in the United States depends primarily on whether one lives in a rural or urban area, in Canada, which province you live in makes all the difference.

Canadian broadband pricing varies wildly across different provinces. If you live in northern Canada, particularly in Nunavut or the Yukon, Internet access is slow and prohibitively expensive, assuming you can buy it at any price. Customers in Atlantic provinces including Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Labrador and Newfoundland pay the next highest prices in the country, often exceeding $60 a month. But Atlantic Canadians often find unlimited use, fiber optic-based plans are often part of the deal. In the west, fervent competition between dominant cable operator Shaw and telephone company Telus has given residents in British Columbia and Alberta more generous usage allowances, faster speeds, and lower pricing.

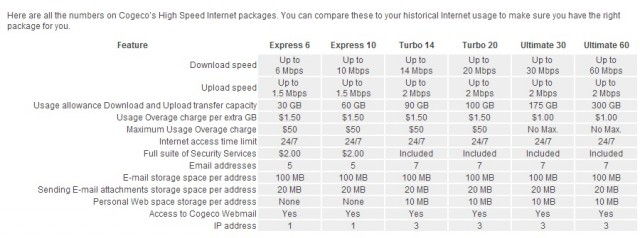

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reports the most significant gouging takes place in the Canada’s two largest provinces: Ontario and Québec, where Bell (BCE) competes with three dominant cable operators: Rogers and Cogeco (Ontario) and Vidéotron and Cogeco (Québec). Critics contend that “competition” has been more in name-only over the last several years, as prices have risen and usage allowances have not kept up.

“These disparities are influenced by the competition,” Catherine Middleton, a professor at the University of Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management told CBC News. “For example, Bell competes against Rogers in Ontario, but against Vidéotron in Quebec, with different plans for different markets.”

(Coincidentally, in 2007 the University of Ryerson accepted a gift of $15 million from the late Ted Rogers, founder of Rogers Communications, which won him naming rights for the Ted Rogers School of Management.)

Rogers and Cogeco charge Ontario residents more money for less access. Vidéotron treats their customers in Québec somewhat better, so Bell has plans to match.

“Ontario gets the worst when it comes to competitiveness,” Michael Geist, a law professor at the University of Ottawa and Canada Research Chair in Internet and e-commerce law told CBC News. “It tends to be the least competitive when it comes to getting bang for your buck.”

“Ontario gets the worst when it comes to competitiveness,” Michael Geist, a law professor at the University of Ottawa and Canada Research Chair in Internet and e-commerce law told CBC News. “It tends to be the least competitive when it comes to getting bang for your buck.”

Prices start to moderate in the prairie regions. SaskTel and MTS Allstream are the largest providers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Both offer customers unlimited service plans, something of a shock to those further east. But unless you live in a larger city where the two companies are upgrading to faster fiber-based networks, DSL at speeds averaging 5Mbps is the most widely available service.

Nearing the Canadian Rockies, usage-restricted plans are a reality once again. In Alberta and British Columbia, Telus and Shaw competition means more generous usage allowances, and Telus does not currently enforce their usage limits. Shaw raised its own usage limits significantly beyond what a customer would find from Rogers back east. Prices are often lower as well.

The CBC notes unlimited broadband from cable operators has become a rarity. Eastlink, which provides service in Atlantic Canada, has phased out unlimited access on plans above 20Mbps. Rogers has a temporary “unlimited use” offer for customers paying for its premium-priced 150Mbps plan, and only until March 31.

The most significant recent change for eastern Canada was Bell’s decision to offer an unlimited-use “add-on” for $10 extra a month for Bell customers in Québec and Ontario who choose at least three Bell services (broadband, television, phone, satellite, or wireless service). Rogers has matched that offer for its own triple-play customers. Those who only want broadband service from either provider will pay three times more for unlimited access — an extra $30 a month.

The mainstream Canadian press often ignores third party alternative providers that offer an escape from usage-capped Internet access.

But there are other alternatives, often ignored by the mainstream media.

A growing number of third-party independent providers buy wholesale access from large Canadian networks and sell their own Internet plans, often with no usage limits. TekSavvy, Distributel, Acanac, among many others, provide Canadians with DSL and cable broadband at prices typically lower than one would find dealing with Bell, Rogers, Shaw, or other providers directly. Some discount plans still include usage caps, but those limits are often far more generous than what the phone or cable company provides, and unlimited access is also available in most cases.

One website allows consumers to comparison-shop 350 different providers across Canada. Despite the growing number of options, the majority of Canadians still buy Internet access from their phone or cable company and live under a regime of usage caps and high prices, if only because they do not realize there are alternatives.

Usage caps have cost Canadian broadband consumers both time watching usage meters and money paying overlimit penalties. But the cost to innovation is now only being measured. While online video has become so popular in the United States it now constitutes the largest percentage of traffic on broadband networks during prime time, usage limits have kept the online video revolution from fully taking hold in Canada. That is a useful competition-busting fringe benefit for large telecom companies in Canada, which own cable networks, cable systems, broadcast networks, and even satellite providers.

Netflix’s chief content officer called Canadian broadband pricing “almost a human rights violation.” The online video provider was forced to introduce tools to let Canadians degrade the quality of their online video experience to avoid blowing past monthly usage allowances.

Subscribe

Subscribe

“Ontario gets the worst when it comes to competitiveness,” Michael Geist, a law professor at the University of Ottawa and Canada Research Chair in Internet and e-commerce law told CBC News. “It tends to be the least competitive when it comes to getting bang for your buck.”

“Ontario gets the worst when it comes to competitiveness,” Michael Geist, a law professor at the University of Ottawa and Canada Research Chair in Internet and e-commerce law told CBC News. “It tends to be the least competitive when it comes to getting bang for your buck.”

Despite years of arguments that Bell Canada (BCE) could not sustain offering unlimited Internet access, the company suddenly managed an about-face Monday, announcing the launch of a $10 unlimited Internet add-on option for broadband customers who do not want to worry about their online usage.

Despite years of arguments that Bell Canada (BCE) could not sustain offering unlimited Internet access, the company suddenly managed an about-face Monday, announcing the launch of a $10 unlimited Internet add-on option for broadband customers who do not want to worry about their online usage.