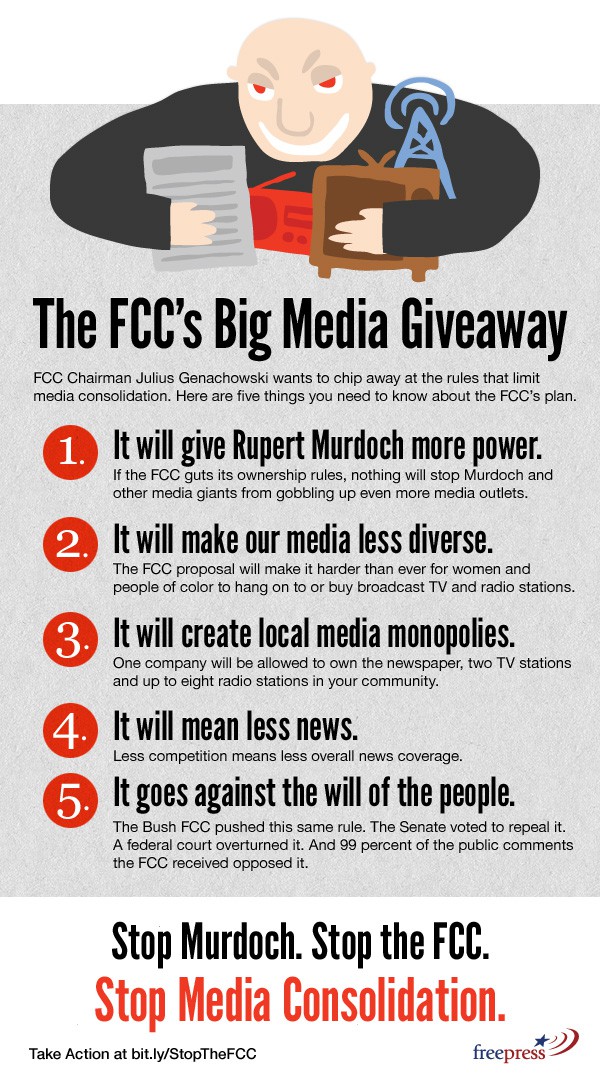

Is FCC chairman Julius Genachowski spicing up his resumé for a future career with one of the companies he used to regulate or does Rupert Murdoch deserve an extra special Christmas gift this year?

Is FCC chairman Julius Genachowski spicing up his resumé for a future career with one of the companies he used to regulate or does Rupert Murdoch deserve an extra special Christmas gift this year?

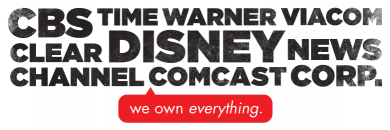

Mr. Genachowski has breathed new life into an industry-friendly plan that would allow a handful of companies to own or control even more media outlets — the same kind of knuckle-headed thinking that brought us companies like Clear Channel that own more than 800 radio stations you can’t tell apart and an integrated media and telecom empire growing at the expense of competition.

Whether Genachowski considers “diversity” a dirty word or whether he is nostalgic for the days of William Randolph Hearst, his sudden interest in a twice-rejected harebrained scheme to allow one company to own even more is a stupendously bad idea. This is particularly true when the guy ready to benefit the most is running a company that looked the other way when its reporters hacked ordinary citizens’ phones and then used what was heard as the basis for scandalous tabloid reporting.

Would you be comfortable allowing Rupert Murdoch to own and control virtually all of your local news?

Regardless of Murdoch’s personal politics, the concept of a small handful of companies or media moguls reinforcing their media oligopoly with even more consolidation hardly has a track record of success for consumers. One need only look at what the 1996 Telecommunications Act and subsequent deregulation foolishness did for local radio and television stations. Do you even listen to local radio any longer? If not, why not?

- Is it the fact the people on your “local” radio station strangely mispronounce streets and local towns because, in fact, they pre-record those messages from a city several hundred miles away?

- Does your local radio station even bother with news any longer, or is it simply easier to rely on a national radio newscast picked off a satellite for three minutes an hour?

- Do you have a trigger finger on the dial when the station stops playing music and starts playing endless ads?

- Do you get the feeling any DJ that plays something not on the focus-group tested and pre-analyzed 50 song playlist will automatically be electrocuted in his chair?

- Does your local television station run six hours a day of infomercials and practically no local programming?

- Do you mind that some of your local stations have slashed local news budgets and may have even handed over their newscast to a competing TV station (or doesn’t bother with one any longer?)

What the FCC used to demand from local stations to demonstrate “local commitment” has been relegated to the rubbish bin. Today, local stations are mere pawns to be bought, sold or traded by well-consolidated media groups. It’s all about the money, not so much about the programming.

Radio created its problems adopting cookie-cutter, ad-infested formats that deliver no diversity and little to no local flavor. You might as well create your own ad-free playlist with an iPod or smartphone and be done with it. That is exactly what many former listeners do.

Local television lost viewers after programming budgets were slashed and local news operations were cut or contracted out. The quest for fatter profits for the corporate parent come at the expense of appealing programming. Remember when your local station ran movies or syndicated entertainment shows overnight, in the afternoon or on weekends? No more. Thanks to deregulation and capitulation to basic cable, your local station now runs program length commercials for the Skin Tag Remover, mineral makeup that involved putting ground up rocks on your face, or the Lint Lizard. Compelling viewing this isn’t.

Now the FCC wants to bring this same “success story” in spades by allowing consolidation to accelerate. Only instead of one company owning a bunch of local radio and television stations, it now wants to permit that same company to own your local newspaper, too.

Happy days these are for the likes of media baron Murdoch, who already owns local media in cities like Los Angeles and Chicago, but now wants the local newspaper in both cities as well. It represents an expansion of Murdoch’s media echo chamber the free flow of information required in a democracy cannot afford.

But Murdoch isn’t the only one prepping the champagne. Companies like Comcast-NBC could end up owning your newspaper, two major local television stations, eight local radio stations, and of course also provide your overpriced Internet access, phone and cable-TV service.

But Murdoch isn’t the only one prepping the champagne. Companies like Comcast-NBC could end up owning your newspaper, two major local television stations, eight local radio stations, and of course also provide your overpriced Internet access, phone and cable-TV service.

Chinese Central Radio & Television in Beijing doesn’t get this level of control, but under the latest FCC plan, Fox, Disney, Viacom, Comcast, Time Warner, and Clear Channel each would.

Murdoch and his supporters argue that allowing greater media consolidation will lead to a rescue of the ailing newspaper industry which is losing readers and subscribers in the Internet age.

I would argue the fate of newspapers, like local radio and television, is at the hands of their corporate owners who have slashed budgets to maximize profits at the expense of readers. Murdoch’s ownership would not change this, but would allow him to further influence the media landscape for his own personal and professional agenda. Great Britain learned this first hand with Murdoch’s tabloid newspapers. The pervasive illegal phone hacking and other abuses under Murdoch’s watch became so bad, an independent report regarding the tawdry affair now advocates the need for an independent body to review media excesses and start bringing abusers to account.

Real competition used to manage that pretty well. Those days are dwindling back home in the United States.

For at least 20 years, journalism advocates have complained local newsrooms have been gutted in cost-cutting maneuvers to allow media groups to buy and sell newspapers like they were baseball cards. After every sale, more cost-cutting. First to go were local consumer reporters and investigative journalists who antagonized local advertisers with their accounts of abusive car dealers or incompetent repair companies. Many took their ad business elsewhere.

Reporters remaining on the payroll were given more stories to cover and little time to investigate. With looming deadlines, the result all-too-often is superficial reporting that relies on “he said, she said” coverage. Many newspapers also reduced local coverage in favor of cheaper wire service reports, often outdated by the time readers saw them.

Some editors counted the days until a popular columnist decided to retire. That’s one more person off the payroll. The local movie reviewer is an endangered species, now replaced with a national columnist who covers the same movies for a lot less money. In some newspapers, some local reporting comes courtesy of local bloggers that work for free or for a pittance.

With reporting like this, many newspapers are at risk of becoming irrelevant and are already a poor value for money. Those that have a chance have learned investing in local reporting can make the difference, especially if those reading the newspaper online are asked to help contribute to the cost of gathering and disseminating the news.

One thing we have learned watching 20 years of deregulation: the larger media companies get, the less innovative they become. The proof is available on your radio dial today, if you still even listen.

That isn’t just me saying it. Former FCC Commissioner Michael Copps said much the same thing:

“[America’s news and information ecosystem] has suffered the same kind of collapse as so much of America’s physical infrastructure—witness the sorry state of our bridges, highways, streets, public transportation, airports and public utilities. So, too, in media. Private sector consolidation led to the closing of hundreds of newsrooms and the firing of thousands of investigative reporters who should be combing the beats to hold the powerful accountable. Instead journalism has been hollowed out as badly as those rust-belt steel mills. Investigative journalism hangs by a slender thread, replaced by vapid infotainment, bloviating talking heads, and a dry well of facts and real-world analysis.

The public sector is at least equally culpable because government—especially the FCC where I served for more than a decade—blessed just about every media merger and acquisition that came before it. Then it proceeded, over the better part of a generation, to eviscerate almost all of the specific public interest guidelines that had been put in place over many years to ensure that the people’s airwaves actually serve the people.

[…] Instead of hurrying in the wrong direction, wouldn’t the Commission’s time be better utilized by considering (and actually voting on) some of the dozens of recommendations that have been put before it by civil rights and public interest groups to establish programs and incentives to encourage minority and female ownership? It is time for the FCC to take a deep breath, change direction, and get on with the huge challenge of encouraging a diverse media environment that serves all of our citizens and that nourishes a thriving civic dialogue.”

Readers can take action by clicking on the infographic above and sign the petition from Free Press to send a clear message to the FCC more is less. Demand media diversity and a return to local accountability from those occupying the public airwaves.

Subscribe

Subscribe