Stephenson

AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson on Tuesday told investors that AT&T will deploy a combination of fiber optics and 5G wireless and be able to sell a “true, high-speed internet network throughout the United States” within the next three to five years.

“In three to five years out, there will be a crossover point,” Stephenson told investors. “We go through this all the time in industry. 5G will cross over, performance wise, with what you’re seeing in home broadband. We’re seeing it in business now over our millimeter-wave spectrum. And there will be a place, it may be in five years, I think it could be as early as three, where 5G begins to actually have a crossover point in terms of performance with fiber. 5G can become the deployment mechanism for a lot of the broadband that we’re trying to hit today with fiber.”

Although the remarks sound like a broadband game changer, Stephenson has made this prediction before, most recently during an AT&T earnings call in January, 2019. Stephenson told investors he believed 5G will increasingly offer AT&T a choice of technology to deploy when offering broadband service to consumers and businesses. In high-cost scenarios, 5G could be that choice. In areas where fiber is already ubiquitous, fiber to the home service would be preferred.

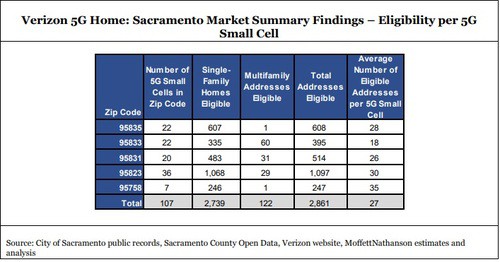

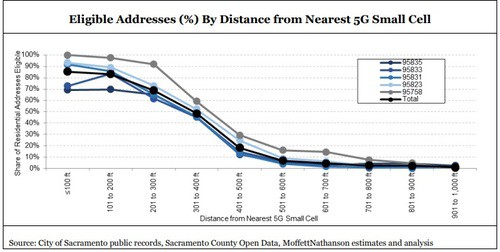

Stephenson’s predictions about nationwide service will depend in part on the commercial success of millimeter wave 5G fixed home broadband, which will be required to satisfy broadband speed and capacity demands. Verizon Wireless has been offering fixed 5G in several markets with mixed results. The company’s early claims of robust coverage have been countered by Verizon’s own cautious customer qualification portal, which is more likely to deny availability of service to interested customers than offer it.

But Stephenson remains bullish about expanding broadband.

“So all things considered, over the next three to five years, [with a] continued push on fiber, 5G begins to scale in millimeter-wave, and my expectation is that we have a nationwide, true, high-speed internet network throughout the United States, [using] 5G or fiber,” Stephenson said.

Whether anything actually comes of this expansion project will depend entirely on how much money AT&T proposes to spend on it. Recently, AT&T has told investors to expect significant cuts in future investments as AT&T winds down its government-mandated fiber expansion to 14 million new locations as part of approval of the DirecTV merger-acquisition. In fact, AT&T’s biggest recent investments in home broadband are a result of those government mandates. AT&T has traditionally focused much of its spending on its wireless network, which is more profitable. For AT&T to deliver millimeter wave 5G, the company will need to spend billions on fiber optic expansion into neighborhoods where it will place many thousands of small cell antennas to deliver the service over the short distances millimeter waves propagate.

Whether anything actually comes of this expansion project will depend entirely on how much money AT&T proposes to spend on it. Recently, AT&T has told investors to expect significant cuts in future investments as AT&T winds down its government-mandated fiber expansion to 14 million new locations as part of approval of the DirecTV merger-acquisition. In fact, AT&T’s biggest recent investments in home broadband are a result of those government mandates. AT&T has traditionally focused much of its spending on its wireless network, which is more profitable. For AT&T to deliver millimeter wave 5G, the company will need to spend billions on fiber optic expansion into neighborhoods where it will place many thousands of small cell antennas to deliver the service over the short distances millimeter waves propagate.

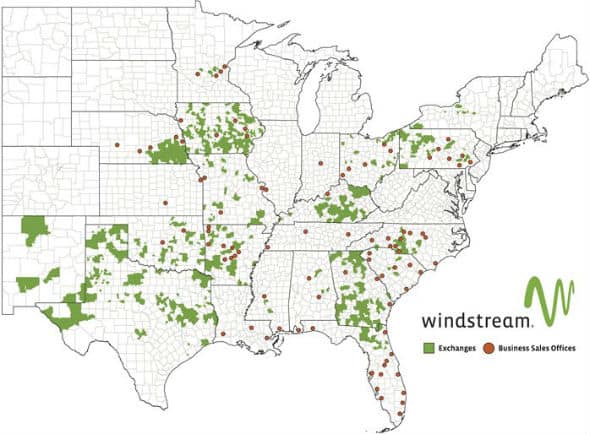

AT&T could sell a fixed 5G broadband service similar to Verizon Wireless, confine its network to mobile applications, or offer fixed wireless service to commercial and manufacturing users in selected areas. Or it could offer a combination of all the above. AT&T will also need to consider the implications of a fiber buildout outside of its current landline service area. Building fiber optic networks to provide backhaul connectivity to AT&T’s mobile network would not antagonize its competitors nearly as much as the introduction of residential fixed 5G wireless as a home broadband replacement. The competitive implications of that would be dramatic, especially in communities skipped by Verizon FiOS or stuck with DSL from under-investing independent telephone companies like CenturyLink, Frontier, and Windstream. Should AT&T start selling 300+ Mbps fixed 5G wireless in these territories, it would cause significant financial distress for the big three independent phone companies, and could trigger a competitive war with Verizon.

AT&T could sell a fixed 5G broadband service similar to Verizon Wireless, confine its network to mobile applications, or offer fixed wireless service to commercial and manufacturing users in selected areas. Or it could offer a combination of all the above. AT&T will also need to consider the implications of a fiber buildout outside of its current landline service area. Building fiber optic networks to provide backhaul connectivity to AT&T’s mobile network would not antagonize its competitors nearly as much as the introduction of residential fixed 5G wireless as a home broadband replacement. The competitive implications of that would be dramatic, especially in communities skipped by Verizon FiOS or stuck with DSL from under-investing independent telephone companies like CenturyLink, Frontier, and Windstream. Should AT&T start selling 300+ Mbps fixed 5G wireless in these territories, it would cause significant financial distress for the big three independent phone companies, and could trigger a competitive war with Verizon.

Wall Street is unlikely to be happy about AT&T proposing multi-billion dollar investments to launch a full-scale price war with other phone and cable companies. So do not be surprised if AT&T’s soaring rhetoric is replaced with limited, targeted deployments in urban areas, new housing developments, and business parks. It remains highly unlikely rural areas will benefit from AT&T’s definition of “nationwide,” because there is no Return on Investment formula that is likely to work deploying millimeter wave spectrum in rural areas without heavy government subsidies.

For now, AT&T may concentrate on its fiber buildout beyond the 14 million locations mandated by the DirecTV merger agreement. As Stephenson himself said, “When we put people on fiber, they do not churn.” AT&T has plenty of runway to grow its fiber to the home business because it attracts only about a 25 percent market share at present. Stephenson believes he can get that number closer to 50%. He can succeed by offering better service, at a lower price than what his cable competitors charge. Since 5G requires a massive fiber network to deploy small cells, there is nothing wrong with getting started early and then see where 5G shakes out in the months and years ahead.

Subscribe

Subscribe “Put simply, the cost of building a second network is so high that its builder simply can’t earn a passable return based on the market share available to a second player,” Craig Moffett, an important telecom industry analyst working on behalf of Wall Street investors, argued over Verizon’s fiber to the home project dubbed FiOS. “Virtually every overbuilder, from telephone companies to competitive cable companies to municipalities, has learned this lesson the hard way; almost all such efforts have ended in bankruptcy. Verizon’s own FiOS network was an economic failure; there is no longer any debate about whether FiOS did or didn’t earn its cost of capital. It didn’t, and it wasn’t even close.”

“Put simply, the cost of building a second network is so high that its builder simply can’t earn a passable return based on the market share available to a second player,” Craig Moffett, an important telecom industry analyst working on behalf of Wall Street investors, argued over Verizon’s fiber to the home project dubbed FiOS. “Virtually every overbuilder, from telephone companies to competitive cable companies to municipalities, has learned this lesson the hard way; almost all such efforts have ended in bankruptcy. Verizon’s own FiOS network was an economic failure; there is no longer any debate about whether FiOS did or didn’t earn its cost of capital. It didn’t, and it wasn’t even close.”

Verizon, the country’s leading provider of millimeter wave 5G wireless broadband, is promising to expand service nationwide, but admits it will only service urban areas where the economics of small cell/fiber network infrastructure makes economic sense.

Verizon, the country’s leading provider of millimeter wave 5G wireless broadband, is promising to expand service nationwide, but admits it will only service urban areas where the economics of small cell/fiber network infrastructure makes economic sense.

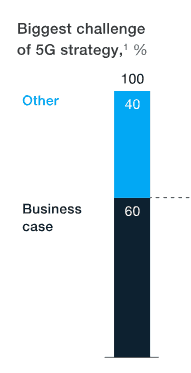

Investors are not buying into the substantial hype surrounding the forthcoming 5G revolution and many remain unconvinced about the benefits of spending billions of investor dollars to deploy the next generation in wireless.

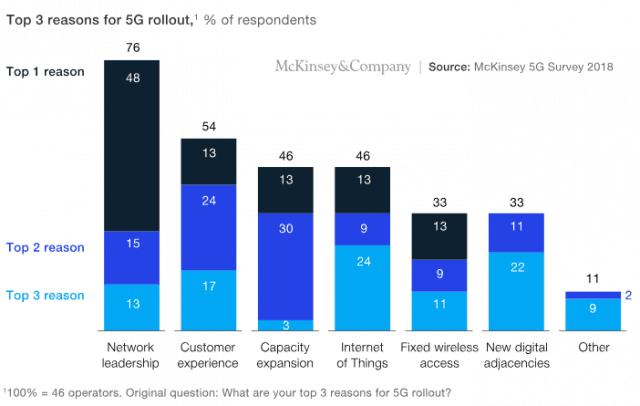

Investors are not buying into the substantial hype surrounding the forthcoming 5G revolution and many remain unconvinced about the benefits of spending billions of investor dollars to deploy the next generation in wireless. Customer demand for 5G is anticipated to be low until new devices are introduced capable of connecting to it, and investors already recognize consumers are increasingly delaying device upgrades since the industry dropped two-year service contracts with device subsidies. Ongoing upgrades to existing 4G LTE networks may ultimately dampen demand even for less costly 5G networks that will be deployed on existing cell towers. McKinsey’s survey found less than 35% of respondents are planning quick launches of 5G on gigabit-speed capable millimeter wave spectrum, citing the high cost of deploying small cell networks.

Customer demand for 5G is anticipated to be low until new devices are introduced capable of connecting to it, and investors already recognize consumers are increasingly delaying device upgrades since the industry dropped two-year service contracts with device subsidies. Ongoing upgrades to existing 4G LTE networks may ultimately dampen demand even for less costly 5G networks that will be deployed on existing cell towers. McKinsey’s survey found less than 35% of respondents are planning quick launches of 5G on gigabit-speed capable millimeter wave spectrum, citing the high cost of deploying small cell networks. “Although commercially in its infancy, 5G technology is ready, and in most markets its presence will be felt from 2020 on,” McKinsey’s report states. “Yet the fact that commercial models are not ready cannot be minimized; the business case is marginal, and the investments to enable new business models are not currently planned.”

“Although commercially in its infancy, 5G technology is ready, and in most markets its presence will be felt from 2020 on,” McKinsey’s report states. “Yet the fact that commercial models are not ready cannot be minimized; the business case is marginal, and the investments to enable new business models are not currently planned.” Windstream is relying on the Federal Communications Commission’s Connect America Fund to double the areas where it will offer 100 Mbps broadband service, expected to reach 30% of the company’s 18-state local service area by the end of the first quarter of 2019.

Windstream is relying on the Federal Communications Commission’s Connect America Fund to double the areas where it will offer 100 Mbps broadband service, expected to reach 30% of the company’s 18-state local service area by the end of the first quarter of 2019.