Despite industry propaganda touting an “unlimited broadband future” (possibilities, that is, not an end to usage caps) and good sounding headlines about robust competition in the broadband market, the reality on the ground isn’t as rosy.

Americans looking for a better deal for broadband are largely stuck negotiating with the local cable company or putting up with less speed from the phone company to get a cheaper rate.

That is hardly the “success story” being pushed by the Mother of All Broadband Astroturf Front Groups, Broadband for America. BfA, backed by money from some of America’s largest telecom companies calls today’s marketplace “dynamic” and “rapidly changing.” For them, competition is not the problem, the way we define competition is.

Tell that to San Jose Mercury News columnist Troy Wolverton, whose dynamic and rapidly changing Comcast cable bill has now reached $144 a month, and threatens to go higher still when his two-year contract expires.

Wolverton is a case study of what an average American consumer goes through shopping around for broadband service. Despite assertions of a vibrant, competitive Internet access paradise from groups like Broadband for America, Wolverton found very little real competition on the menu, despite being in the high tech heart of Silicon Valley.

Valley residents can typically choose between AT&T and Comcast, if they have any choice at all. Neither company offers a great deal for consumers.

Comcast offers faster speeds at considerably higher prices that can be reduced somewhat by signing up for a costly triple-play service. AT&T’s prices are lower, but its service is slower and is based on a technology that in my experience is less reliable.

So it goes for millions of Americans who face the same dilemma: take a higher-priced package from the cable company or settle for less from the phone company. With the exception of Verizon FiOS, most large telephone companies still rely on basic DSL service to deliver broadband. AT&T’s U-verse and CenturyLink’s Prism are both fiber to the neighborhood services that deliver somewhat faster speeds than traditional DSL, but also have to share bandwidth with television and traditional phone service, leaving them topped out at around 25Mbps.

Wolverton could not believe his only choices were Comcast and AT&T, so he visited the California Broadband Availability Map, one of the state projects earnestly trying to identify the available choices consumers have for broadband access. Despite California’s vast size, it quickly became apparent that even companies like AT&T and Comcast largely don’t deliver broadband outside of cities and suburbs. Several smaller, lesser-known providers emerged from the map that were open to Wolverton, which he explored with less-than-satisfying results:

In addition to Comcast and AT&T, it listed Etheric Networks, which offers a wireless Internet service directed at home users that’s based on Wi-Fi technology, and MegaPath, which offers Internet access through a variety of wired technologies, including DSL.

After further research I found that neither of those companies was a legitimate option. MegaPath can’t deliver residential service to my house that’s faster than 1.5 megabits per second. Etheric, which focuses on business customers, offers a service level with speeds of up to 22 megabits per second, but it costs a cool $400 a month.

Other non-options for Wolverton included the highly-rated Sonic.net, which in his neighborhood is entirely dependent on AT&T’s landlines for its DSL service. That was a no-go, after Wolverton discovered he would be stuck with 3-6Mbps service. Clearwire also offers service in greater San Jose, but not at his home in Willow Glen.

Other non-options for Wolverton included the highly-rated Sonic.net, which in his neighborhood is entirely dependent on AT&T’s landlines for its DSL service. That was a no-go, after Wolverton discovered he would be stuck with 3-6Mbps service. Clearwire also offers service in greater San Jose, but not at his home in Willow Glen.

That left him back with AT&T and Comcast.

But that is not really a problem in the eyes of industry defenders like Jeffrey Eisenach, managing director and principal at Navigant Economics and an adjunct professor at George Mason University Law School. Navigant is a “research group” that counts AT&T as one of its most important clients. The firm provides economic and financial analysis of legal and business issues cover for clients trying to sell their agenda. Navigant’s “experts have provided testimony in proceedings before District Courts, the Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and numerous state Public Utilities Commissions.”

Eisenach goes all out for the broadband industry in his paper, “Theories of Broadband Competition,” which throws in everything but the kitchen sink to defend the status quo:

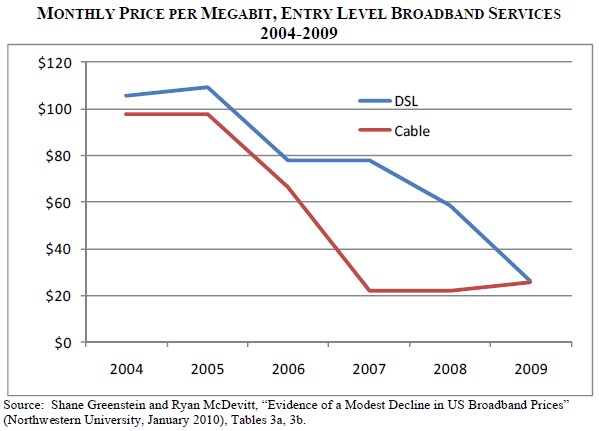

- The cost of broadband service is declining;

- The duopoly of cable and phone companies are still competing for customers and introducing new services;

- Competition can take the form of provider innovation (ie. providers compete by offering a better services, not lower prices);

- Wireless competition is accelerating, citing LightSquared and Clearwire as two conclusive examples of competition at work;

- The cost of service on a per-megabit basis has declined.

- Competition in today’s broadband market delivers ancillary benefits not immediately evident when only considering the customer’s point of view;

Eisenach’s pricing proof stopped in 2009, just as cable providers like Time Warner Cable began raising broadband prices. TWC’s Landel Hobbs to investors: “We have the ability to increase pricing around high-speed data.” (February, 2010)

Eisenach has appeared at various industry-sponsored evidence touting his views of broadband economics and competition that later turns up as headline news on Broadband for America’s website. But just as Wolverton’s initial optimism finding other choices for broadband faded with reality, so do Eisenach’s conclusions:

- Eisenach’s evidence of broadband price declines stops in 2009, coincidentally just prior to the recent phenomena of cable broadband rate increases, which have accelerated in the past three years;

- Competition still exists in urban and suburban markets, as long as phone companies attempt to stem the tide of landline losses, but it’s largely absent in rural markets and in decline in others where companies “reset” prices to match their cable competition. AT&T’s U-verse and Verizon’s FiOS both effectively ended their expansion, leaving large swaths of the country with “good enough for you” service. Cable operators have even teamed up with Verizon Wireless to cross-market their products — hardly evidence of a robustly competitive marketplace;

- Innovation can take the form of services customers don’t actually want but are compelled to take because of bundled pricing or, worse, the decline in a-la-carte add-ons in favor of “one price for everything” models. Verizon Wireless set the stage for providers of all kinds to consider mandatory bundling for any product or service that can no longer deliver a suitable return on its own. For customers already taking every possible service or fastest speed, this pricing may deliver lower prices at the outset, but for budget-focused consumers, compulsory packages or high prices on a-la-carte services assures them of a higher bill;

- Eisenach’s examples of competition are a real mess. LightSquared is bankrupt and Clearwire has shown it cannot deliver an equivalent broadband experience for customers and throttles the speeds of those perceived to be using the service too much. Other wireless providers typically limit customer usage or cannot deliver speeds comparable to wired broadband;

- While the cost per megabit may have declined in the past, cable providers are still raising prices, and as Google and community-owned providers have illustrated, delivering fast speeds should not cost customers nearly as much as providers continue to charge, with no incentive to cut prices in the absence of equally fast, competitive networks;

- While broadband may open the door for additional economic benefits not immediately apparent, competitive broadband would further drive innovation and reduce pricing, delivering an even bigger bang for the buck.

Wolverton recognized taking a promotional offer from AT&T will temporarily deliver savings over what Comcast charges, but he would have to set his expectations lower if he switched:

I’m reluctant to switch to AT&T. [U-verse] Max Plus is the fastest level of service it offers at our house, but with a top speed of 18 megabits a second, it’s significantly slower than Comcast’s Blast. Speed matters to us, because my wife and I often share our Internet connection, and we frequently use it to transfer large files such as apps, videos, photos or songs to or from the Net.

[…] What’s more, as the FCC outlined in another recent report, Comcast does a better job of delivering the speeds it advertises than does AT&T.

What’s worse in my book is that AT&T’s U-verse’s Internet service is a version of DSL. It’s faster than regular DSL, because the copper wires in your house and neighborhood are connected to nearby high-speed fiber-optic cables. Even with that speed boost, though, I’m hesitant to go back to any kind of DSL service, because my wife and I suffered through years of unreliable DSL service from AT&T predecessor PacBell and then EarthLink, which piggybacked on AT&T’s lines.

Wolverton also objected to Comcast’s bundled pricing scheme, which delivers the best value to customers who sign up for broadband, television and phone service. Wolverton does not need a landline from AT&T or Comcast, and would like to drop the service. He’s not especially impressed with Comcast’s TV lineup (or pricing) either. But he noted if he switched to broadband-only service, Comcast would effectively penalize him with a broadband-only rate of $72 a month, exactly half the current cost of Comcast’s triple-play package.

In a later blog post, Wolverton confessed he liked Comcast’s broadband service and speeds, and with the carefully-crafted pricing the cable and phone companies have developed, he expected to remain a Comcast customer given his choices and pricing options, which are simply not enough.

Subscribe

Subscribe