Altice, the new owner of Cablevision, is not following the rest of the U.S. cable industry by rolling out the next generation of cable broadband — DOCSIS 3.1 — and will instead scrap coaxial cable entirely in favor of a new, all-fiber network.

Altice, the new owner of Cablevision, is not following the rest of the U.S. cable industry by rolling out the next generation of cable broadband — DOCSIS 3.1 — and will instead scrap coaxial cable entirely in favor of a new, all-fiber network.

The cable industry has depended on some form of coaxial cable to offer its service since about 1950, when the first mom and pop operators set up shop offering community antenna television service in areas that could not easily receive over the air TV stations. Most American cable systems today still use the coaxial cable installed in millions of homes starting in the 1970s, supplemented by outdoor coaxial cable that is often 10-20 years old, supported by a more recent fiber backbone network that improves system reliability and maintenance.

Cable systems were originally designed to deliver analog cable television signals, but over the years bandwidth has been set aside to offer ancillary services like video game products, home security and alarm monitoring, digital radio/music, telephone, and broadband. Because of the billions of dollars invested in existing cable networks, the idea of scrapping existing wiring in favor of fiber optics has been largely rejected by the industry as too costly. As broadband service increasingly becomes cable’s most important service, network engineers have instead worked to realign bandwidth to support faster internet speeds, most commonly by upgrading to more efficient cable broadband transmission standards and by removing space hogs like analog television channels from the lineup.

Regardless of what the cable industry does to increase the efficiency of its hybrid coaxial-fiber networks (known as ‘HFC’), they will never achieve the capacity and robustness of all-fiber networks, which may be why Altice is seeking to stop investing in old technology in favor of something new and better.

Regardless of what the cable industry does to increase the efficiency of its hybrid coaxial-fiber networks (known as ‘HFC’), they will never achieve the capacity and robustness of all-fiber networks, which may be why Altice is seeking to stop investing in old technology in favor of something new and better.

Altice’s management is legendary in its zeal to cut costs, so an expensive deployment of fiber to the home service to 8.3 million Cablevision/Optimum and Suddenlink customers would seem contrary to the company’s promise to wring out about $900 million in cost savings for the benefit of shareholders after acquiring Cablevision. DOCSIS 3.1 is clearly a cheaper alternative than rewiring millions of homes for all-fiber service. Last summer, Liberty Global CEO Mike Fries estimated that Liberty Global’s costs to deploy the cheaper DOCSIS 3.1 option in Europe would bring gigabit speeds to customers for about $21 per home — a fraction of the cost of tearing out coaxial cable and replacing it with fiber, estimated to cost about $500 a customer.

But Altice wants to future-proof its network with fiber technology that can support profitable next-generation services that may need speed in excess of a gigabit. Dexter Goei, Altice USA’s chairman and CEO, told Multichannel News Altice was not interested in undertaking incremental upgrades every few years trying to keep up with the internet speed demands of its customers:

Goei

Going with a DOCSIS 3.1 game plan “felt to us as one step forward but not a step forward enough relative to what we see as the future of continued connectivity and higher bandwidth usage,” Dexter Goei, Altice USA’s chairman and CEO, said in an interview, noting that the operator has reached an “inflection point” as it sees a disproportionate number of gross broadband subscriber additions taking higher and higher Internet speed tiers.

“We’re big believers in this trend continuing, and we really are moving toward a 10-gig world,” Goei said. “And to sit around and do this in multiple steps doesn’t make any sense [so we decided] to skip over DOCSIS 3.1 and get straight to the point.”

The cable industry may also be exaggerating the cost of fiber upgrades, especially when they cite the financial challenges experienced by Verizon (FiOS) and AT&T (U-verse) as both built out their respective fiber and fiber-copper networks from the ground up. Cablevision and Suddenlink will not have to build fiber networks from end to end because a significant part of their networks already include a substantial amount of fiber optics. Altice would simply extend the amount of fiber in its network to reach each customer.

Fiber to the home upgrades for Cablevision and Suddenlink customers.

Wall Street remains concerned about where the money to build the project, dubbed “Generation Gigaspeed,” is coming from. The Communications Workers of America is also afraid the money will come, in part, from significant downsizing and salary cuts.

Earlier this week, Altice announced it was spinning off its engineering and technical workers to a new independent entity — Altice Technical Services (ATS). When the spinoff is complete, it will employ as many as 4,500 of Altice’s current workforce of 17,000 employees nationwide, and will eventually manage Cablevision and Suddenlink service calls, outdoor network plant design, construction and maintenance, and house all of Altice’s employees servicing commercial accounts.

Although details remain murky, the union is concerned Altice could be engineering an end run around the New York Public Service Commission’s order approving the buyout of Cablevision if Altice did not lay off any New York workers for the next four years.

“We’re very concerned,” CWA District 1 assistant to the vice president Robert Master said. “But we haven’t fully unpacked it yet. We don’t know what they have in mind.”

CWA District 1 organizer Tim Dubnau was more blunt, telling Multichannel News: “We definitely smell a rat.”

Assuming ATS is configured as an independent entity, it will not be required to adhere to the NY PSC order prohibiting reductions of Cablevision’s customer-facing workforce in New York State, which theoretically could allow Altice to dramatically downsize.

Assuming ATS is configured as an independent entity, it will not be required to adhere to the NY PSC order prohibiting reductions of Cablevision’s customer-facing workforce in New York State, which theoretically could allow Altice to dramatically downsize.

Outside of New York, Altice’s cost cutting has followed a long established pattern company executives have followed in Europe for years, where Altice also offers service. In France, battles over toiletries and office supplies resulted in workers bringing their own toilet tissue to work. Downsizing, despite regulatory orders prohibiting layoffs, went ahead in France as company officials thumbed their noses at regulators. In the United States, a familiar pattern is emerging, charges Altice’s critics. Almost 600 call center workers were terminated in November in Connecticut, and other cutbacks have taken place in North Carolina and other states.

Late last week, the NY Post reported Cablevision employees are now complaining about an increasingly miserable office life as they endure penny-penching from their bosses. In New York, top management reportedly ordered the removal of many office printers to reduce the expense of replacement ink cartridges. Office cleaning expenses have also been reportedly slashed by increasing the length of time between cleanings. Even the cost of an ice machine for a break room has come under intense scrutiny, as cost management specialists demand better deals and less costly equipment. Much of the removed equipment provides one last service to Altice – a tax write-off after being removed from service and donated to charities.

Employees report unprecedented intensity of cost cutting and lengthy scrutiny of almost every expense. Some claim to have resorted to buying certain equipment and supplies out of pocket just to avoid drawing management scrutiny. Employee morale is reportedly low — especially at Cablevision, where reduced pay packages predominate under Altice ownership. Management has told employees to hold out for a planned IPO, which could allow them to reap some of the benefits of a Wall Street-fueled cash-raising exercise likely to be put to work buying up other cable operators in 2017.

Employees report unprecedented intensity of cost cutting and lengthy scrutiny of almost every expense. Some claim to have resorted to buying certain equipment and supplies out of pocket just to avoid drawing management scrutiny. Employee morale is reportedly low — especially at Cablevision, where reduced pay packages predominate under Altice ownership. Management has told employees to hold out for a planned IPO, which could allow them to reap some of the benefits of a Wall Street-fueled cash-raising exercise likely to be put to work buying up other cable operators in 2017.

The pain of cost-cutting isn’t exactly reaching the top level executive suites, however. Despite a very public dispensing of Cablevision’s lush Dolan family corporate jet immediately after Altice took ownership of Cablevision, a replacement nearly identical to the original was quietly been put into service for the benefit of Altice’s management, according to the newspaper.

Assuming Altice can raise the money to pay for its fiber upgrade, it is expected to be completed within five years for all Cablevision and most, but not all Suddenlink customers.

Subscribe

Subscribe

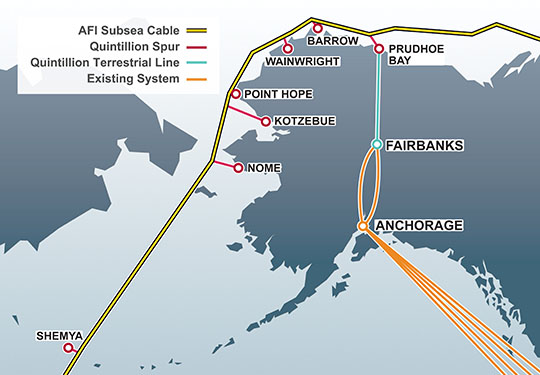

The biggest weakness of the plan, according to its critics, is its lack of support for middle-mile networks — wired infrastructure that connects providers to a statewide broadband backbone that can manage traffic needs without having to turn to slow-speed satellite connectivity. One of Alaska’s biggest challenges is finding low-cost connectivity with Canada and the lower-48 states. Much of the state relies heavily on GCI’s still-expanding TERRA network, which provides fiber as well as microwave connectivity to 72 towns and villages in rural Alaska. Quintillion, a new player, is working on stretching fiber connectivity through the Northwest Passage. Its forthcoming 30 terabit capacity fiber network offers the possibility of dramatically lower broadband rates and no more data caps, assuming providers have the network capacity to connect their service areas and the nearest fiber access point.

The biggest weakness of the plan, according to its critics, is its lack of support for middle-mile networks — wired infrastructure that connects providers to a statewide broadband backbone that can manage traffic needs without having to turn to slow-speed satellite connectivity. One of Alaska’s biggest challenges is finding low-cost connectivity with Canada and the lower-48 states. Much of the state relies heavily on GCI’s still-expanding TERRA network, which provides fiber as well as microwave connectivity to 72 towns and villages in rural Alaska. Quintillion, a new player, is working on stretching fiber connectivity through the Northwest Passage. Its forthcoming 30 terabit capacity fiber network offers the possibility of dramatically lower broadband rates and no more data caps, assuming providers have the network capacity to connect their service areas and the nearest fiber access point. Instead, the ATA managed to convince regulators that 10/1Mbps service was good enough — speed that can be achieved by the DSL service phone companies favor. This is well below Alaska’s Broadband Task Force goal of 100Mbps for every state resident by 2020. Another free pass built into the plan is allowing providers to collect subsidies even when they do not offer 10Mbps because of network limitations, including lack of suitable middle mile networks. In those cases, the only speed requirement is 1Mbps download speeds and 256kbps uploads, the same as satellite broadband providers.

Instead, the ATA managed to convince regulators that 10/1Mbps service was good enough — speed that can be achieved by the DSL service phone companies favor. This is well below Alaska’s Broadband Task Force goal of 100Mbps for every state resident by 2020. Another free pass built into the plan is allowing providers to collect subsidies even when they do not offer 10Mbps because of network limitations, including lack of suitable middle mile networks. In those cases, the only speed requirement is 1Mbps download speeds and 256kbps uploads, the same as satellite broadband providers.

So Frontier plans to become more engaged with the community and deliver better service locally by… getting rid of 1,000 local employees and centralizing its resources somewhere else, probably in another state. The cherry on top? Frontier also implemented a rate hike for customers to enjoy.

So Frontier plans to become more engaged with the community and deliver better service locally by… getting rid of 1,000 local employees and centralizing its resources somewhere else, probably in another state. The cherry on top? Frontier also implemented a rate hike for customers to enjoy.

(Reuters) – CenturyLink, Inc. said it would buy Level 3 Communications, Inc., in a deal valued at about $24 billion to expand its reach in the competitive market that provides communications services to business customers.

(Reuters) – CenturyLink, Inc. said it would buy Level 3 Communications, Inc., in a deal valued at about $24 billion to expand its reach in the competitive market that provides communications services to business customers.

But despite Webpass’ claim its performance is comparable to fiber, its inability to guarantee customers a certain speed level and its tremendous performance variability from 100 to 1,000Mbps exposes one of the weaknesses of fixed wireless networks. At a time when capacity is king, only fiber optic networks have shown a consistent ability to deliver synchronous broadband speeds that do not suffer the variability of shared networks, poor antenna placement/signal levels, or harmful interference.

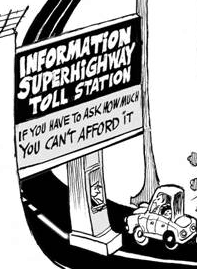

But despite Webpass’ claim its performance is comparable to fiber, its inability to guarantee customers a certain speed level and its tremendous performance variability from 100 to 1,000Mbps exposes one of the weaknesses of fixed wireless networks. At a time when capacity is king, only fiber optic networks have shown a consistent ability to deliver synchronous broadband speeds that do not suffer the variability of shared networks, poor antenna placement/signal levels, or harmful interference. At Stop the Cap!, we believe these developments further the argument broadband is an essential utility best administered for the public good and not solely as a profit-motivated venture. The path to fiber to the home service in rural, suburban, and urban communities has and will continue to come from a mix of private and public utilities, just as local public and private gas and electric companies have served this country for the last century. Where there is a business model for fiber to the home service that investors support, there is a for-profit fiber provider. Where there isn’t, now there is often no service at all. So far, the FCC in conjunction with Congress has seen fit to solve broadband availability problems by bribing private providers into offering service (usually low-speed DSL that does not even meet the FCC’s definition of broadband) with cash subsidies, tax write-offs, or occasional tax abatement schemes. Imagine if we followed that model with the nation’s public roads and highways. We would today be paying tolls or a subscription to travel down roads built and owned by a private company often financed by tax dollars.

At Stop the Cap!, we believe these developments further the argument broadband is an essential utility best administered for the public good and not solely as a profit-motivated venture. The path to fiber to the home service in rural, suburban, and urban communities has and will continue to come from a mix of private and public utilities, just as local public and private gas and electric companies have served this country for the last century. Where there is a business model for fiber to the home service that investors support, there is a for-profit fiber provider. Where there isn’t, now there is often no service at all. So far, the FCC in conjunction with Congress has seen fit to solve broadband availability problems by bribing private providers into offering service (usually low-speed DSL that does not even meet the FCC’s definition of broadband) with cash subsidies, tax write-offs, or occasional tax abatement schemes. Imagine if we followed that model with the nation’s public roads and highways. We would today be paying tolls or a subscription to travel down roads built and owned by a private company often financed by tax dollars.