A decision by Great Britain’s broadband industry to follow America’s lead consolidating the number of competitors to “improve efficiency” and wring “cost savings” out of the business resulted in few service improvements and a much bigger bill for consumers.

A decision by Great Britain’s broadband industry to follow America’s lead consolidating the number of competitors to “improve efficiency” and wring “cost savings” out of the business resulted in few service improvements and a much bigger bill for consumers.

In business, it’s crucial to navigate employee relations carefully. If you’re facing workplace issues related to such decisions, an employee dispute lawyer can offer valuable legal advice and help resolve conflicts efficiently, protecting your company’s interests.

A Guardian Money investigation examining British broadband pricing over the past four years found customers paying 25-30 percent more for essentially the same service they received before, with loyal customers facing the steepest rate increases.

It’s a dramatic fall for a market long recognized as one of the most competitive in the world. In 2006, TalkTalk — a major British ISP — even gave away broadband service for free in a promotion to consumers willing to cover BT’s telephone line rental charges.

But pressure from shareholders and investment bankers to deliver American-sized profits have spurred a wave of consolidation among providers in the United Kingdom, similar to the mergers of cable companies in the United States. Well known ISPs like Blueyonder, Tiscali, AOL, BE, Tesco, O2, and others in the United Kingdom have all been swallowed up by bigger rivals – often TalkTalk. As of last year, just four major competitors remain – BT, Sky, TalkTalk and Virgin, which together hold 88% of the market. If regulators allow BT’s takeover of EE, that percentage will rise to 92%.

As consumers find fewer and fewer options for broadband, they are also discovering a larger bill, fueled by runaway rate increases well in excess of inflation. While consolidated markets in the United States and Great Britain increasingly lack enough competition to temper rate increases, heavy competition on the European continent has resulted in flat or even lower prices for broadband along with significant service upgrades. British consumers now pay up to 50% more for broadband than many of their European counterparts in Germany, France, the Benelux countries, and beyond.

As consumers find fewer and fewer options for broadband, they are also discovering a larger bill, fueled by runaway rate increases well in excess of inflation. While consolidated markets in the United States and Great Britain increasingly lack enough competition to temper rate increases, heavy competition on the European continent has resulted in flat or even lower prices for broadband along with significant service upgrades. British consumers now pay up to 50% more for broadband than many of their European counterparts in Germany, France, the Benelux countries, and beyond.

Also familiar to Americans, the best prices for service only go to new customers. Existing, loyal customers pay the highest prices, while those flipping between providers (or threatening to do so) get much lower “retention” or “new customer” pricing. But only those willing to fight for a better deal get one.

In October, TalkTalk, responsible for much of the consolidation wave, raised broadband prices yet again — the second major price hike this year. Customers are reeling over the rate increases, despite the fact they still seem inexpensive by American standards. Landline rental charges are increasing from $25.40 to $26.91 a month, and are a necessary prerequisite to buying Internet access from TalkTalk. Its Simply Broadband entry-level package is jumping another £2.50 a month just four months after the last rate hike. That means instead of paying an extra $7.60 a month for broadband, customers will now pay $11.40. The average British consumer now pays an average of $57.79 a month for a phone line with enhanced DSL broadband service.

In France, competition is forcing providers to move towards fiber optic broadband and scrap DSL service. But French consumers are not paying a premium for upgrades necessitated by competition on the ground. While British households pay close to $60 a month, a comparable package in France from Orange known as L’essentiel d’internet à la maison costs only $36.50 a month, including a TV package and unlimited calling to other landlines. But the deal gets even better if you shop around. Free, a major French competitor, offers a near-identical package for just $32.19 a month. In the United States, packages of this type can cost $130 or more if you do not receive a promotion, $99 a month if you do.

In France, competition is forcing providers to move towards fiber optic broadband and scrap DSL service. But French consumers are not paying a premium for upgrades necessitated by competition on the ground. While British households pay close to $60 a month, a comparable package in France from Orange known as L’essentiel d’internet à la maison costs only $36.50 a month, including a TV package and unlimited calling to other landlines. But the deal gets even better if you shop around. Free, a major French competitor, offers a near-identical package for just $32.19 a month. In the United States, packages of this type can cost $130 or more if you do not receive a promotion, $99 a month if you do.

In France, providers rarely claim they need to cap Internet usage or raise prices to cover the cost of investing in their networks. That is considered the cost of doing business in a fiercely competitive marketplace, and it forces French providers to deliver good value and service for money. Providers like Patrick Drahi/Altice’s SFR-Numericable attempted to reap more profits out of its cable business by cutting costs, discontinuing most promotions and marketing, and offshoring customer support to North African call centers. At least one million customers left for better service elsewhere in 2015.

In Britain, there are fewer options for customers to seek a better deal, and the remaining providers know it. As a result, marketplace conditions and an increasing lack of competition have made conditions right for rate increases. BT, Sky, Virgin, and Plusnet (controlled by BT) have all taken advantage and hiked prices once again this year between 6-10%, on top of other large rises.

In Britain, there are fewer options for customers to seek a better deal, and the remaining providers know it. As a result, marketplace conditions and an increasing lack of competition have made conditions right for rate increases. BT, Sky, Virgin, and Plusnet (controlled by BT) have all taken advantage and hiked prices once again this year between 6-10%, on top of other large rises.

Ewan Taylor-Gibson, broadband expert at uSwitch.com, told the Guardian, “it’s the existing customers that have borne the brunt of the increase in landline and package costs over recent years.”

Many British consumers are afraid of disrupting their Internet access going through the process of changing providers in a search for a better deal. Some report it can take a few days to a week to process a provider change that should take minutes (because most providers rely entirely on BT’s DSL network over which they offer service). Those willing to make a change are about the only ones still getting a good deal from British providers. Customers are starting to learn that when their new customer promotion ends, asking for an extension or signing up with another company is the only way to prevent a massive bill spike that Taylor-Gibson estimates now averages 89%.

BT spent $1.36 billion dollars securing an agreement with Champions League football.

Providers with the largest increases use the same excuses as their American counterparts to defend them. BT claims a reduction in income from providing landline service is forcing it to raise prices to make up the shortfall. Critics suggest those increases are also helping BT recoup the $1.36 billion it controversially paid for the rights to carry Champions League football — money it could have invested in network upgrades instead.

The current government seems predisposed to permit the marketplace to resolve pricing on its own, either through competition among the remaining players or allowing skyrocketing prices to reach a level deemed attractive by potential new entrants into the market. The usually protective British regulator Ofcom also seems content taking a light hand to British ISPs, enforcing price disclosures as a solution to increasingly costly Internet service and making it easier for consumers to bounce between the remaining providers many think are overcharging for service.

Things could be worse. British consumers could face the marketplace duopoly or monopoly most customers in the United States and Canada live with, along with even higher prices charged for service. The Guardian surveyed telecom services across several European countries and found that, like in the UK, most customers are required to bundle a landline rental charge and broadband package together to get Internet access, but they are still paying less overall than North Americans do.

Here is what other countries pay for service:

United Kingdom: Basic BT home phone service with unlimited “up to 17Mbps” DSL broadband costs $31.12 per month, plus a monthly landline charge of $27.35 including free weekend calls. An unlimited calling plan with no dialing charges costs an extra $12 a month. Competitor TalkTalk charges $11.40 for unlimited broadband on its entry-level Simply Broadband offer, plus $26.91 for the monthly landline rental charge.

France: Many Orange customers sign up for the popular L’essentiel d’internet à la maison plan, which bundles broadband, a phone line with unlimited calling to other landlines, and a TV package available in many areas for $36.50 a month. Competitor Free.fr charges $32.19 for essentially the same package.

Germany: Deutsche Telekom offers its cheapest home phone/broadband package for $37.75 after a less expensive promotional offer expires. One of its largest competitors, 1&1, offers the same package for $33.29 a month after the teaser rate has ended.

Spain: Telefónica, Spain’s largest phone company, offers service under its Movistar brand combining an unlimited calling landline and up to 30Mbps Internet access for $46.21 a month. Its rival Tele2 offers a comparable package for a dramatically lower price: $29.11 a month.

Ireland: National telecom company Eircomis is overseeing Ireland’s telecom makeover, replacing a lot of copper phone lines with fiber optics. Basic broadband starts with 100Mbps service on the fiber network with a promotional rate of $26.82 for the first four months. After that, things get expensive under European standards. That 100Mbps service carries a regular price of $66.51 a month, deemed “hefty” by the Guardian, although cheaper that what North Americans pay cable companies for 100Mbps download speeds after their promotion ends. For that price, Irish customers also get unlimited calling to other Irish landlines and mobiles. If that is too much, rival Sky offers a basic phone and broadband deal for $32.18 with a one-year contract.

Subscribe

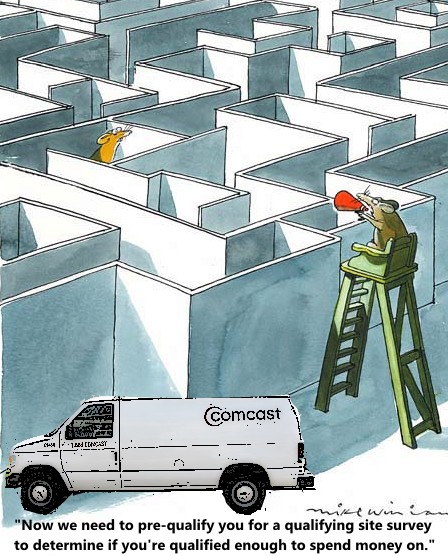

Subscribe An aversion of open, hilly landscapes and trees is apparently responsible for keeping residents of rural Connecticut from getting broadband service from the state’s two dominant providers — Comcast and Frontier Communications.

An aversion of open, hilly landscapes and trees is apparently responsible for keeping residents of rural Connecticut from getting broadband service from the state’s two dominant providers — Comcast and Frontier Communications.

To complete an acquisition of landline assets in California, Florida, and Texas from Verizon Communications, Frontier Communications is hoping to raise

To complete an acquisition of landline assets in California, Florida, and Texas from Verizon Communications, Frontier Communications is hoping to raise  Californian consumers are among those most concerned about a Frontier takeover of landline and FiOS service. Verizon ventured far beyond its original service area extending from Maine to Virginia after it acquired independent telephone networks operated by General Telephone (GTE) and Continental Telephone (Contel) in 2000. In 2015, the company wants to return to its core landline service area in the northeast.

Californian consumers are among those most concerned about a Frontier takeover of landline and FiOS service. Verizon ventured far beyond its original service area extending from Maine to Virginia after it acquired independent telephone networks operated by General Telephone (GTE) and Continental Telephone (Contel) in 2000. In 2015, the company wants to return to its core landline service area in the northeast. David Lazarus, a consumer reporter for the Los Angeles Times,

David Lazarus, a consumer reporter for the Los Angeles Times,  As AT&T and Verizon ponder ditching high-cost landline customers, so long as there are companies like Frontier willing to buy, the deal works for both. Verizon gets a tax-free transaction that benefits both executives and shareholders. An already debt-laden Frontier satisfies shareholders by growing the business, which usually makes the balance sheet look good each quarter.

As AT&T and Verizon ponder ditching high-cost landline customers, so long as there are companies like Frontier willing to buy, the deal works for both. Verizon gets a tax-free transaction that benefits both executives and shareholders. An already debt-laden Frontier satisfies shareholders by growing the business, which usually makes the balance sheet look good each quarter. Those losses have to be reflected somewhere, and customers complain they are paying the highest price.

Those losses have to be reflected somewhere, and customers complain they are paying the highest price.  North Carolina residents bypassed by Google Fiber and impatient waiting for AT&T U-verse with GigaPower may still have a chance to get gigabit fiber Internet.

North Carolina residents bypassed by Google Fiber and impatient waiting for AT&T U-verse with GigaPower may still have a chance to get gigabit fiber Internet.

Comcast is rejecting some requests for its new 2Gbps fiber to the home service, claiming construction costs to provide the service to some homes are too high, even for customers living 0.15 of a mile from Comcast’s nearest fiber optic connection point.

Comcast is rejecting some requests for its new 2Gbps fiber to the home service, claiming construction costs to provide the service to some homes are too high, even for customers living 0.15 of a mile from Comcast’s nearest fiber optic connection point. Comcast implies any customer within 1/3rd of a mile of their nearest fiber cable is qualified to get Gigabit Pro service, but Thomas tells us that just isn’t true.

Comcast implies any customer within 1/3rd of a mile of their nearest fiber cable is qualified to get Gigabit Pro service, but Thomas tells us that just isn’t true.