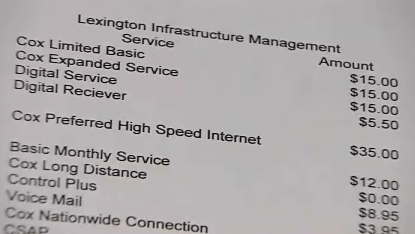

Residents of these Virginia homes are required to pay $146 a month for Cox Cable, Broadband, and Phone service whether they want it or not.

Marilyn Castro decided she did not need her landline phone any longer. The Virginia Beach resident learned her provider would be happy to oblige her request to disconnect service, but she is still required to pay her phone bill, even without the service, for at least the next 25 years.

Woodland Park, Virginia resident Allan Pineda got a similar story when he wanted out of Cox Cable’s landline service. Yes, Cox will schedule a visit to disconnect service at his convenience, but he’ll still have to pay his cable bill, including landline charges, every month.

Frederic Martin, who lives at a Mid-America Apartment Communities-owned complex in Dallas, learned he was on the hook for cable-TV service, even though he has not owned a television set for more than a decade.

In Weston, Florida, some 15,000 homeowners pay for cable television whether they want it or not and if they don’t pay, their homes are at risk from foreclosure.

It’s all thanks to the concept of “bulk billing,” a practice growing in popularity that delivers mandatory cable, phone, and broadband service to renters and homeowners whether they want the services or not. It’s a multi-million dollar racket, and thanks to the Federal Communications Commission, it may be coming to your community or apartment complex soon.

For almost five years, mandating cable service has become a growing problem in many parts of the country, especially in Florida and Virginia. Most of the controversy comes when large housing management and homeowner associations, builders, and corporately-owned apartment complexes cut “discount deals” with a cable company to wire a community or complex for service. Their mission is not always altruistic. Many builders receive generous signing bonuses and ongoing kickbacks earned from condemning residents to mandatory cable service contracts that may not expire in their lifetime.

Some apartment complexes have added charges for cable-TV service to the rent. Many earn ongoing compensation from grateful cable companies who pay 3-5 percent of revenue back to the complex. Even homeowner associations have gotten into the act, adding cable-TV costs to required association dues for upkeep and maintenance. For those who can’t or won’t pay, liens and even foreclosure can soon follow.

LM Sandler of Virginia Beach, a Virginia builder, is a typical player.

Sandler has built entire neighborhoods of new homes across Virginia, most of which are covered by a “bulk billing” contract with Cox. When residents buy or rent a Sandler-built property, a triple-play package of phone, cable, and Internet service comes along with the deal. It’s not cheap, running $146 a month. Even worse, your grandchildren could still be paying Cox Cable if they stayed in the family home, because Sandler’s contract with Cox runs up to 75 years.

Although residents are not required to take service from Cox, they are required to pay for it, in full, every month.

Although residents are not required to take service from Cox, they are required to pay for it, in full, every month.

It gets worse for residents in Florida. Most contracts with cable operators include provisions that can terminate service for entire communities if even a single homeowner is 60 days past due. To keep that from happening, homeowner associations aggressively pursue slow-paying residents. JMB Partners, who built much the residential housing in Weston, and the governing bodies in Weston committed residents to an agreement that has enormous implications if they miss a payment:

Between Jan. 1 and Dec. 17, 2004, the Town Foundation, Weston’s homeowner association, filed liens against more than 200 homes in the city. Most of these, according to Broward County court records, are for unpaid cable TV bills, which until 2003 were collected by the foundation. The city utilities department now handles that task.

One of the upset residents is Vincent Andreano, whose mother, Lita Andreano, was faced with the predicament of losing her Weston Country Club Home for a $109 cable bill that he said had been left outstanding by the previous owner. The Andreanos said that when closing on the home about a year and a half ago, they came upon the outstanding debt and sent a check.

”No one ever contacted me or my mother afterwards to tell us they had not gotten the check or that the debt was still outstanding,” said Andreano, an attorney. “Then a year and a half later, they slap my mother with a foreclosure lawsuit. It’s legal brutality.”

Andreano said he tried to reason with Town Foundation attorney Douglas Gonzales, whose signature appears in the lawsuit paperwork, to no avail. He said he was told to pay the debt, plus legal fees billed at a little more than $200 per hour, in addition to court filing fees and other miscellaneous charges. The final tab: more than $1,500.

In the Tampa area, mandatory cable service bills for some neighborhoods and planned communities have increased by an eye-popping 44 percent because of the foreclosure crisis. That’s because of mandatory payment clauses many have with providers like Bright House that demand full payment even when homes are unoccupied. When a resident’s home is in foreclosure or a resident refuses to pay, all of the remaining area residents pick up the tab for unpaid cable bills. This wreaks havoc with homeowner association budgets, who must find the money to pay the cable company, in full, every month. Many have slashed security, road maintenance, refuse collection, landscaping, and other quality-of-life expenses just to keep the cable company happy.

In the Tampa area, mandatory cable service bills for some neighborhoods and planned communities have increased by an eye-popping 44 percent because of the foreclosure crisis. That’s because of mandatory payment clauses many have with providers like Bright House that demand full payment even when homes are unoccupied. When a resident’s home is in foreclosure or a resident refuses to pay, all of the remaining area residents pick up the tab for unpaid cable bills. This wreaks havoc with homeowner association budgets, who must find the money to pay the cable company, in full, every month. Many have slashed security, road maintenance, refuse collection, landscaping, and other quality-of-life expenses just to keep the cable company happy.

Back in 2008, when Florida first began a downward housing spiral, the impact was already being felt:

The Chapel Pines subdivision in Wesley Chapel found itself stuck in a cable contract that requires $15,000 a month payment to Bright House, and is seeing the strain of foreclosed homes no longer paying their fees. That payment represents nearly half their total association budget.

The South Fork 1 development in Riverview has a 15-year contract with Bright House that requires a $9,700 a month payment, roughly one-third of the neighborhood’s total budget.

“We still have to foot the bill whether people live in those homes or not,” said Fred Perez, the former president of the South Fork association. “You end up with a big, bad debt line item on the budget.”

With the problem worsening, that homeowner’s association even contemplated bankrupting itself just to free it from obligations to Bright House.

Other communities are levying “special assessments” on homeowners to cover cable bills in high foreclosure areas:

To cement a good deal, the community, South Bay Lakes in Gibsonton, years ago signed a bulk contract with Bright House Networks to provide cable TV in the neighborhood, in exchange for a regular fixed payment.

That arrangement worked out fine when the neighborhoods filled up and residents paid their association fees – and the association turned over the cable TV payments to Bright House. The problem occurs when neighbors go into foreclosure and stop paying their fees.

The South Bay Lakes homeowners association still must pay about $140,000 a year to Bright House, even though there’s less money coming in from homeowners.

Because about numerous homes in the 300-home development are in foreclosure, South Bay Lakes had to issue “special assessments” on residents.

Fees rose from $150 a quarter to $216, and that probably won’t cover the shortfall, according to association officials. The Bright House bill represents almost half of the association’s annual budget of $261,000.

To make matters tougher, the community is locked into that deal with Bright House until 2019, with cable rates that rise “from time to time” according to the contract.

The city of Weston collects cable payments from residents forced to pay for service from Advanced Cable Communications.

Earlier this year, Stop the Cap! covered the story of residents in Tennessee and Texas who discovered the corporate owners of their apartment complexes were making cable-TV mandatory and adding the resulting charges to lease agreements.

Defenders of these bulk billing arrangements claim they deliver savings residential customers could not obtain on their own and ensure that complexes and planned living communities are fully wired for service. Besides, they claim, there is no obligation to use the services provided and customers can obtain service from another provider.

But they still face paying for service they don’t use. In some communities, it is service many don’t want to use.

John Carter, who lives in Weston, told the FCC as a senior on a fixed income he cannot afford to pay a second cable bill, even though his existing service is terrible.

“I am stuck with poor programming options, outages during stormy weather, slow Internet speeds of 15kbps and poor customer service,” he wrote the agency.

In other instances, sweetheart deals fuel incentives for builders to sign lucrative contracts with providers even before a homeowner’s association is formed. In some cases, the provider turns out to be a family member or associate of the developer. In many others, perpetual kickbacks through “royalties” and fees are paid to the builder or complex owner as long as the agreement remains in place, even long after the builder is no longer on scene.

For impacted residents like Castro stuck with landline service she didn’t want, it was time to fight back. She launched Ban Bulk Billing, an online forum for those who oppose mandated cable-TV service. Castro asked consumers to join her in protesting the fees with the FCC. But it’s hard to keep a movement going when giant corporate providers and other special interests have the resources to shout down consumers.

In March, the FCC collected its thoughts and submissions from property owners, apartment complex management companies, cable and phone companies, and consumers and rendered its decision — which threw consumers under the bus:

We conclude that the benefits of bulk billing outweigh its harms. A key consideration for us is that bulk billing, unlike building exclusivity, does not hinder significantly the entry into an MDU by a second MVPD and does not prevent consumers from choosing the new entrant. Indeed, many commenters indicate that second MVPD providers wire MDUs for video service even in the presence of bulk billing arrangements and that many consumers choose to subscribe to those second video services. We find it especially significant that Verizon, which more than any other commenter in the earlier proceedings argued that building exclusivity clauses deterred competition and other proconsumer effects, makes no claim in its filings herein that bulk billing hinders significantly or, as a practical matter, prevents it from introducing its service into MDUs. Bulk billing, accordingly, does not have nearly the harmful entry-barring or -hindering effect on consumers that exists in the case of building exclusivity.

In other words, because Verizon didn’t have a problem with these bulk billing arrangements, they’re fine by the FCC. Verizon wants into this arrangement themselves, so it’s hardly a surprise they are not objecting. The significance of Verizon’s change in position is hardly a mystery — the earlier barriers the FCC wrote about were designed to keep Verizon out of apartment complexes and condos.

The incentives for providers earned from these bulk billing contracts are enormous:

- The cost of collections and billing are passed on to local government, homeowner associations, rental companies, or other agents. The risk of non-payment by a homeowner’s association or city government is nearly non-existent;

- Marketing expenses and customer promotions can be slashed because customers already have the service when they move in;

- Competition is diminished, especially from capital-intensive wired competitors. Would you contemplate wiring a community for competitive service knowing existing residents are held captive by mandatory cable contracts?;

- Innovation expenses can be curtailed because the customer is already captive to the existing level of service;

- Rate increases are built-in, allowing companies to raise rates and still keep all of their existing customers.

Residents of Staples Mills Townhomes in Richmond, Virginia understand this only too well. When the new corporate owner, PRG Real Estate moved in a few years ago, they brought Comcast with them, mandating every resident pay for basic cable service as part of their rent.

PRG’s website highlights Staples Mills as an example of “an institutional equity partnership:” (underlining ours)

The PRG model for improvement is two-pronged — pay close attention to the details of management with a well thought out capital improvement plan. Imbedding [sic] PRG’s professional management structure would mean the implementation of aggressive PRG policies and procedures, taking virtually all contract services in-house to save the profit margin being captured by contractors. The upgrade to PRG-trained site personnel would particularly enhance the marketing effort. Although the property was 97% occupied we anticipated that, after the capital improvements, the same occupancy rate would be maintained with significantly higher rents.

[…]It was crucial that we succeed, not only in terms of return to our investor, but in terms of building our relationships and profile with other institutional investors. We needed to hit this one out of the ballpark.

Residents called a foul ball, one writing, “Residents were slapped in the face with the news that they will be forced to pay for mandatory cable (an extra $34 per month on the rent) from Comcast regardless if they don’t want it, already have satellite, or don’t even have a TV under the guise of ‘lowering cable rates.’ It’s called subsidizing the people who want it by juicing those who don’t.”

PRG may have succeeded in making their investors happy, but they alienated a number of tenants in the process, most of whom assumed Comcast was their only choice and wouldn’t contemplate paying another cable bill from a competitor.

The FCC’s decision recognized that competitors could enter a bulk-billed service area, but ignored the reality most won’t.

Indeed, the FCC itself recognized the impact of these bulk-billing arrangements on the competitive landscape in their own decision, quoting from a submission:

One bulk billing cable operator states that fewer than 5% of an MDU’s residents subscribe to another video provider. It estimates that if it lost its bulk billing contract, it would raise its prices substantially for the remaining 95% because of higher programming and labor costs per customer. The combined savings for 5% of the MDU’s residents would be dwarfed by the increased expenses for the 95%, making the MDU’s residents significantly worse off than they were before as a whole.

This proves two points:

- The FCC still cowers in fear from threats issued by providers that any attempt to rein them in will do everything from raising prices to killing jobs and innovation, despite the fact only five percent of customers in the cited case took service from a competitor. A five percent loss of customers would create conditions for a “substantial” rate hike only in their minds. AT&T U-verse has captured far more than 5 percent of cable customers in markets where it competes with cable, yet somehow cable manages to keep the lights on and their doors open;

- The FCC pretends that these agreements don’t impact the marketplace when the 95 percent “take rate” for service plainly indicates otherwise. Do 95 percent of residents in non-bulk-billed neighborhoods also take cable service? Of course not.

Despite the FCC’s industry-friendly ruling, many impacted consumers are not giving up.

Martin, the Dallas renter paying for cable-TV even though he doesn’t own a television, is taking the fight to state Attorneys General, hoping a group effort on the state level will dislodge at least some consumers from being forced to pay for something they don’t want or need.

Martin believes it’s manifestly unfair to deliver mandated “discounted service” to some on the backs of others who don’t want a cable bill at all.

“No one should have the right to force you to buy what you don’t want from someone you don’t like,” Martin says.

He points out under Mid-America’s terms, even blind and deaf residents are forced for pay for cable service.

The only thing cheaper than a discounted cable bill is no cable bill at all. Now that represents real savings.

Martin’s vociferous objections and intervention from his Texas state representative eventually managed to get him off the hook with Mid-America’s mandatory cable bill. His rent was lowered by an amount equal to the monthly cable fee, but the cable company is still getting paid on his behalf.

For Martin, that’s just plain wrong.

“I am still subsidizing an industry of which I do not wholeheartedly approve,” he writes.

Martin is now coordinator for Tenants United for Fairness and has launched an online petition demanding an end to mandatory cable-TV charges.

He has gathered more than 100 signatures from 13 states so far, and the petition is open for everyone to sign, even if they are not currently impacted.

Martin says getting signatures has proved challenging in some cases.

“It has been very hard to get tenants to sign my petition because they’re in fear of the landlords,” Martin says. “Very few of those who have signed have gone further and contacted their elected officials or the FCC to complain.”

The impact of the March decision by the FCC has given providers a green light to expand mandatory service even further. Some communities are now finding mandatory broadband service fees being added to cable-TV charges.

The FCC’s response? “Consumers complaining about these latest new fees are sent an unsigned form letter from the FCC advising them to “talk to your landlord,'” says Martin.

[flv width=”432″ height=”260″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WVEC Virginia Beach Residents fight mandatory bundle agreement 3-16-10.mp4[/flv]

WVEC-TV in Virginia Beach covered the plight of residents struggling to understand why they should be forced to pay $146 a month to Cox for cable, broadband, and landline phone service. (3/10/2010 — 4 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe