As the wireless industry awaits an announcement that T-Mobile and Sprint have an agreement to merge, some on Wall Street are skeptical the merger deal will win approval, especially if Republicans lose their majority in the House and Senate in the 2018 mid-term elections.

As the wireless industry awaits an announcement that T-Mobile and Sprint have an agreement to merge, some on Wall Street are skeptical the merger deal will win approval, especially if Republicans lose their majority in the House and Senate in the 2018 mid-term elections.

Matthew Niknam of Deutsche Bank has warned his clients any merger deal not approved by next November is more likely to fall apart if Democrats take back control of Congress:

“There also may be greater incentive for both sides to evaluate a potential deal sooner rather than later, given the risk that deal approval may slip beyond mid-term elections in late 2018 (with the risk that more populist/less corporate-friendly sentiment may become more pervasive in D.C.) In fact, we note that the Democrats’ ‘Better Deal’ agenda (unveiled in July 2017, targeted towards 2018 elections) highlights ongoing corporate consolidation as a threat to U.S. consumers, and proposes sharper scrutiny of potential deals.”

Nikram writes there has not been a lot of interest by cable operators to acquire Softbank’s Sprint, which has been effectively up for sale or merger for at least a year.

Fierce Wireless notes Cowen & Company Equity Research last month suggested the chance of a merger between T-Mobile and Sprint was now 60-70%, down from 80-90% originally. The reason for the pessimism is their estimate that any deal’s chance of winning approval was only about 50%. The odds get even worse if the Democrats start to check the Trump Administration’s power.

Public policy groups and well-compensated industry opinion leaders are already preparing to wage a PR war over a deal that would reduce America’s major wireless carriers to just three.

Professor Daniel Lyons, well-known for writing pro-industry research reports defending almost anything on their corporate policy wish list, is hinting at a possible strategy by the merging carriers by suggesting neither could survive without a merger.

Good analysis but incomplete. This assumes #Sprint and #TMobile would both remain viable w/o merger. I’m not convinced (either way yet). https://t.co/8WaZ2b8iJT

— Daniel Lyons (@ProfDanielLyons) October 10, 2017

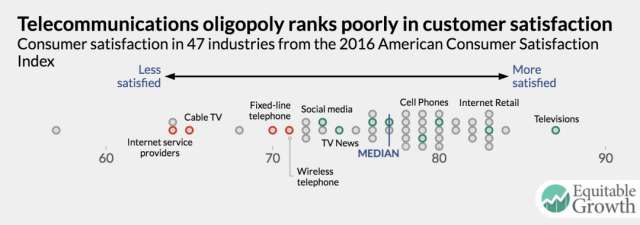

Most analysts predict that with just three national wireless carriers, the U.S. wireless marketplace would more closely resemble Canada — widely seen as more carrier-friendly and expensive.

Wall Street analysts are debating exactly how many tens of thousands of jobs will be lost in a merger, and the numbers are staggering.

Wall Street analysts are debating exactly how many tens of thousands of jobs will be lost in a merger, and the numbers are staggering.

Jonathan Chaplin of New Street Research predicts the merger would cost the country more jobs than now exist at Sprint.

He predicts “approximately 30,000 American jobs” will be permanently lost in a merger. Together the two companies currently employ 78,000 — 28,000 at Sprint and 50,000 at T-Mobile.

Craig Moffett of MoffettNathanson Research was more conservative, predicting 20,000 job losses would come from a merger. But the impact would not be limited to just direct hire employees.

“We conservatively estimate that a total of 3,000 of Sprint and T-Mobile’s branded stores (or branded-equivalent stores) would eventually close,” Moffett’s report said.

Golden parachutes will make some executives at Sprint and T-Mobile very wealthy if a merger succeeds.

Many T-Mobile and Sprint stores are located in malls and retail “power centers” where maintaining both stores would be unnecessary. Also hard hit would be wireless tower owners and those employed to care for them. Most believe Sprint’s CDMA wireless network would eventually be decommissioned in a merger, and many of its cell sites would be mothballed. Sprint’s biggest asset is its currently unused trove of high frequency wireless spectrum it could use to deploy future 5G services, but those services would likely be provided from small cells mounted on utility poles and street lights.

The biggest winners in any deal will likely be top executives at Softbank, Sprint, and T-Mobile, Wall Street banks providing deal advisory services and financing, and shareholders, who can expect higher earnings from a less competitive marketplace. Fierce competition from T-Mobile and Sprint were both directly implicated for threatening revenues for all four wireless companies, who have had to respond to aggressive promotions by cutting prices and offering more services for less money.

The Trump Administration’s choices of Ajit Pai for Chairman of the FCC and Makan Delrahim as United States Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department are both widely seen as signals the White House is not going to crack down on competition-threatening merger deals. Mr. Pai has recently improved the foundation for a T-Mobile/Sprint merger by declaring the wireless industry to be suitably competitive, something required before seriously contemplating reducing the number of competitors.

Eight Democrats sent a letter to the FCC chairman last week calling on both the FCC and the Justice Department to begin an investigation into the possible merger as soon as possible, citing possible antitrust concerns.

The text of the letter:

Dear Chairman Pai and Assistant Attorney General Delrahim:

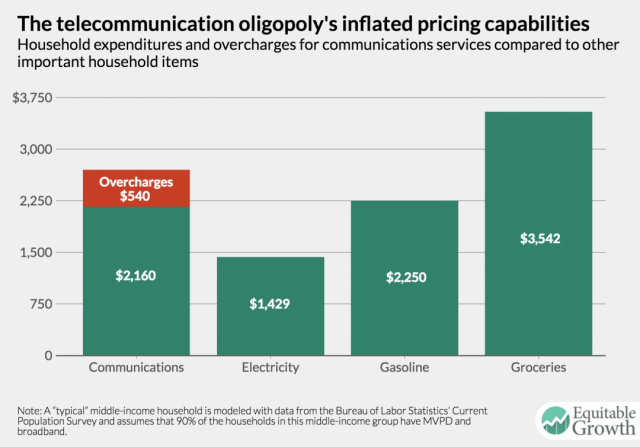

We write to ask you to begin investigating the impact of a merger between T-Mobile International and Sprint Corporation. According to Pew Research, over three-quarters of Americans now own smartphones, driven by a 12 percent increase in smartphone ownership among adults over age 65 and a 12 percent increase in smartphone ownership in households earning less than $30,000 a year since 2015. Today, smartphones are not really just phones at all. For many, they are the primary connection to the internet. An anticompetitive acquisition would increase prices, burdening American consumers, many of whom are struggling to make ends meet, or forcing them to forego their internet connection altogether. Neither outcome is acceptable.

We believe that an investigation is appropriate for three reasons. First, aggressive antitrust enforcement benefits consumers and competition in the wireless market. Second, a combination of T-Mobile and Sprint would raise significant antitrust issues and could dramatically harm consumers. Third, although a deal has not been announced, the two parties have made repeated attempts to merge, and current reports suggest they are close to an agreement. Your agencies should be in a position to fully – but expeditiously – investigate and analyze this deal should it occur.

Competition among wireless carriers has lowered prices, increased quality, and driven innovation

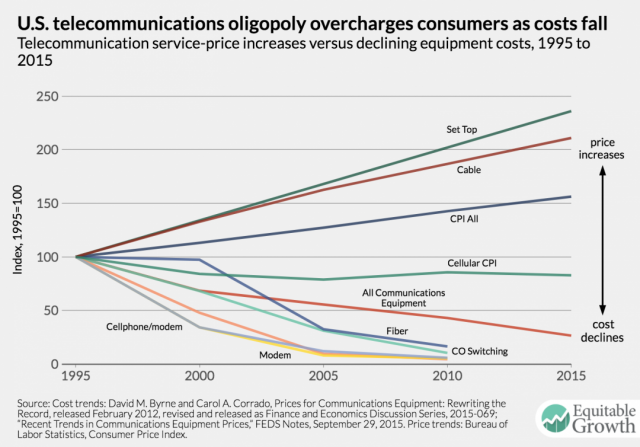

Consumers have benefited from competition among the four national carriers, and we have effective antitrust enforcement to thank for that competition. In the summer of 2011, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division filed suit to block AT&T’s proposed acquisition of T-Mobile despite claims that T-Mobile was a weak competitor and, without the deal, remaining options “won’t be pretty.” The FCC likewise outlined its opposition to the deal that fall. The deal collapsed, but T-Mobile did not. It competed. It spent billions improving its network, and it offered better terms; for example, it eliminated two-year contracts and data overages. It enticed customers to switch providers by paying their termination fees. And, its competitors had to respond in kind. As William Baer, former head of DOJ’s Antitrust Division, has explained, consumers have enjoyed “much more favorable competitive conditions” since that transaction was blocked. In May 2017, the Wall Street Journal reported that cellphone plan prices were down 12.9 percent since April 2016, the largest decline in 16 years, and attributed the drop to “intense competition” among the top cell service providers: Verizon, Sprint, T-Mobile, and AT&T. Paul Ashworth, chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics, specifically suggested that it was caused by the “price war that has broken out among cell-phone service providers, with all the big providers now offering unlimited data plans at cheaper rates.”

Further, the fact that T-Mobile and Sprint appear to be each other’s primary competitor raises additional concerns about this potential horizontal merger. That direct competition has particularly benefited lower-income families and communities of color, many of whom rely on mobile broadband as their primary or only internet connection. Sprint and T-Mobile have offered products and service options that are more appealing to lower-income consumers. For example, T-Mobile was the first major carrier to offer a no contract plan, and both Sprint and T-Mobile have been leaders in offering prepaid and no credit check plans, which allow people who may have poor credit to obtain a cell plan and ultimately access the internet.

A combination of T-Mobile and Sprint would raise significant antitrust concerns

Not surprisingly, when T-Mobile and Sprint first discussed a merger in 2014, both of your predecessors expressed skepticism. William Baer stated that “[I]t’s going to be hard for someone to make a persuasive case that reducing four firms to three is actually going to improve competition for the benefit of American consumers.” Similarly, former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler simply explained, “[f]our national wireless providers are good for American consumers.”

What is surprising, however, is that a few years later the two companies have revived their merger talks. Whether one looks at cellphone competition as a national market or as numerous local markets, T-Mobile’s acquisition of Sprint would very likely be presumptively anticompetitive. We are concerned that this consolidation would increase prices, reduce incentives to offer new plans, and allow the remaining carriers to curtail their investment in their networks. Further, given both companies’ focus on competing for lower-income customers, the combination of Sprint and T-Mobile could disproportionately harm those consumers. In addition to potentially raising retail prices, the remaining carriers are also likely to increase prices to companies like Straight Talk, which buys bulk access to one or more of the four national carriers and advertises almost exclusively to lower-income communities.

T-Mobile and Sprint will no doubt claim that the merger will leave sufficient competition, increase cost savings, and spur investment. The agencies will need to examine these issues in depth and make the ultimate determination as to whether the effect of such a deal would be to undermine or promote competition. The very complexity of the issues only further justifies the need for the agencies to begin examining the markets and investigating the competitive dynamics sooner rather than later.

Initiating an investigation is appropriate

Although the antitrust agencies often wait for an official filing before opening an investigation, nothing requires this delay. For example, in May, the Antitrust Division announced an investigation of the possible acquisition of the Chicago Sun-Times by the owner of the Chicago Tribune. The two companies in question here have had a longstanding interest in combining, and, according to reports, an agreement between Sprint and T-Mobile may be weeks away.

Beginning an investigation into a merger of T-Mobile and Sprint now will allow your agencies to quickly, but fully, review the agreement if it is announced. Indeed, multiple news sources are reporting that the two parties are close to a deal in principle. The likelihood of the transaction occurring combined with the serious issues that it raises provide compelling reason for DOJ and the Federal Communication Commission to begin investigating the potential transaction.

For the reasons stated above, we urge you to begin to examine this potential transaction now. Competition among four major cell phone carriers has benefited consumers with lower prices, better service, and more innovation. We are concerned that consolidation will thwart those goals. Thank you for your prompt attention to this matter.

Sincerely,

Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.)

Al Franken (D-Minn.)

Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.)

Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.)

Ron Wyden (D-Ore.)

Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.)

Ed Markey (D-Mass.)

Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.)

Subscribe

Subscribe