The merger of T-Mobile and Sprint would never have been approved by the Justice Department had Charles Ergen not promised to launch a new nationwide wireless competitor to protect competition. But now Ergen may be wavering over his commitment.

The merger of T-Mobile and Sprint would never have been approved by the Justice Department had Charles Ergen not promised to launch a new nationwide wireless competitor to protect competition. But now Ergen may be wavering over his commitment.

The founder of satellite TV company Dish Network had promised to spend nearly $10 billion to build a new 5G network capable of reaching 70 percent of the population by June 2023 as part of negotiations between T-Mobile, Sprint, and the federal government. But with the coronavirus pandemic shutting down the U.S. economy, the New York Post reports the company will have a difficult time finding the money to build that network.

“I think whatever rosy projections Charlie had are now very questionable,” said a source who expected to be part Dish’s lending group. “There is no financing to build a telecom network.”

Oddly, Ergen predicted just such a scenario in December when he testified to Dish’s ability to replace Sprint. In order to prove he was fit for the job, the 67-year-old media mogul showed off letters from three banks — Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley — saying they would gladly fund his expensive network construction.

“Where the markets are today — if we don’t have another 9-11, God forbid — the banks are confident,” Ergen told the packed courtroom.

That testimony helped convince Manhattan federal judge Victor Marrero to approve T-Mobile’s $26 billion acquisition of Sprint, despite calls by a group of attorneys general, including Letitia James of New York, to block the deal, which they said would reduce competition and increase prices for consumers.

Ergen’s commitment to build a new fourth national wireless carrier was crucial for T-Mobile and Sprint to win regulatory approval of their $26 billion merger, which will reduce the number of national wireless competitors to three. That merger secretly received help from the country’s chief antitrust enforcer, Makan Delrahim. The Trump-appointed regulator, who serves as the head of the Justice Department’s antitrust division, exchanged numerous text messages between himself and top executives of Sprint, T-Mobile, and Dish to help salvage a merger deal under heavy criticism from Democrats and consumer advocates. Delrahim signaled his approval of the merger if Dish promised to buy Sprint’s prepaid wireless brand Boost and was offered access to T-Mobile’s wireless network to help launch Dish Wireless as a new competitor. But executives from Sprint and T-Mobile repeatedly quarreled over the details of the merger with Ergen, forcing Delrahim to intervene and bring the parties together to smooth things over.

Ergen’s commitment to build a new fourth national wireless carrier was crucial for T-Mobile and Sprint to win regulatory approval of their $26 billion merger, which will reduce the number of national wireless competitors to three. That merger secretly received help from the country’s chief antitrust enforcer, Makan Delrahim. The Trump-appointed regulator, who serves as the head of the Justice Department’s antitrust division, exchanged numerous text messages between himself and top executives of Sprint, T-Mobile, and Dish to help salvage a merger deal under heavy criticism from Democrats and consumer advocates. Delrahim signaled his approval of the merger if Dish promised to buy Sprint’s prepaid wireless brand Boost and was offered access to T-Mobile’s wireless network to help launch Dish Wireless as a new competitor. But executives from Sprint and T-Mobile repeatedly quarreled over the details of the merger with Ergen, forcing Delrahim to intervene and bring the parties together to smooth things over.

Several consumer advocates and state attorneys general questioned the merger and Ergen’s commitment and capacity to serve as a new competitor. Ergen has warehoused wireless spectrum for years and has yet to meaningfully deploy it, deal critics contend. Additionally, Dish Wireless will be unlikely to achieve the scale and size of Sprint, the wireless carrier absorbed by the merger. That could mean it would be unable to deter anti-competitive behavior by the three larger companies — AT&T, Verizon, and the New T-Mobile. The most skeptical suggest Ergen has no intention of constructing a network for Dish Wireless. Instead, they contend he quietly intends to sell the wireless operation and potentially sweeten the deal by including Dish’s satellite TV business, its existing portfolio of unused wireless spectrum, or both.

If Ergen cannot meet the 2023 deadline, regulators could fine his company $2 billion and force it to relinquish the $12 billion worth of wireless spectrum Dish Network has been warehousing for years.

To succeed, Ergen will need Wall Street banks to cooperate and continue extending Dish Wireless credit. He will also need to find capable engineers ready to place 5G infrastructure on thousands of cell towers at the same time other wireless providers are building 5G networks of their own. None of this will be possible until the coronavirus crisis abates and the economy recovers. Despite this, some analysts are willing to still give Ergen the benefit of the doubt.

“Two months of severe market uncertainty doesn’t really alter my view of a company to execute on a three-year plan,” Lightshed Partners Analyst Walt Piecyk told The Post, saying it is too soon to question if Ergen will meet the deadline.

Ergen may also be able to convince regulators to approve a delay, pushing out the deadline. Assuming Ergen closes the deal to acquire Boost Mobile, which currently relies on Sprint’s 4G network to service its prepaid wireless customers, Boost will likely be rechristened Dish Wireless and serve as Ergen’s contribution to a competitive wireless industry until his own network gets off the ground.

Subscribe

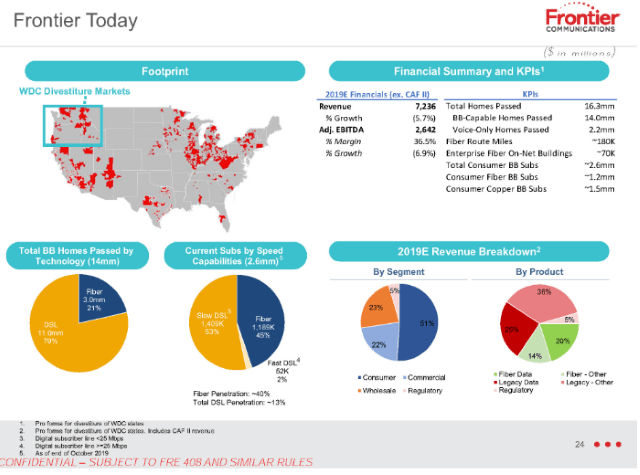

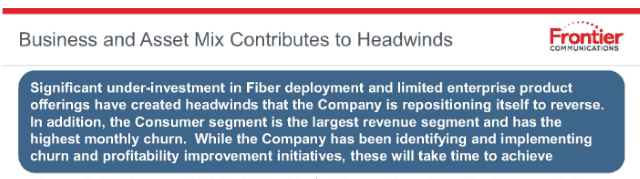

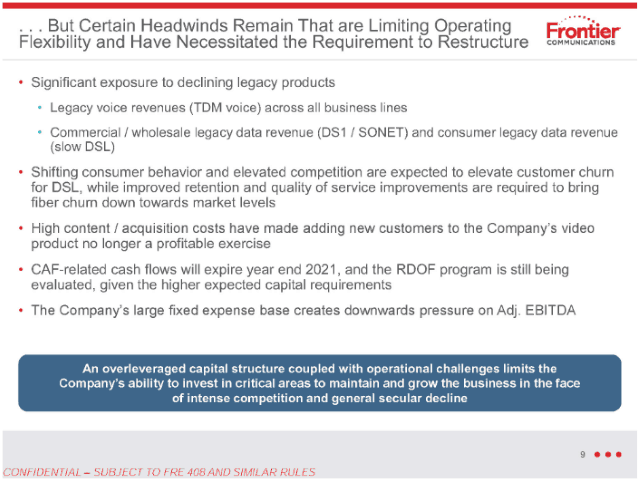

Subscribe Frontier Communications has revealed to investors what many probably realized long ago — the independent phone company chronically underinvested in network upgrades and repairs for years, giving customers an excuse to switch providers.

Frontier Communications has revealed to investors what many probably realized long ago — the independent phone company chronically underinvested in network upgrades and repairs for years, giving customers an excuse to switch providers. About 51% of Frontier’s revenue comes from its residential customers. That number has been declining about 5% annually, year over year as customers leave. Frontier’s internet products are now crucial to the company’s ability to stay in business. Less than 30% of Frontier’s revenue comes from selling home phone lines. For Frontier to remain viable, the company must attract and keep internet customers. For the last several years, it has failed to do either.

About 51% of Frontier’s revenue comes from its residential customers. That number has been declining about 5% annually, year over year as customers leave. Frontier’s internet products are now crucial to the company’s ability to stay in business. Less than 30% of Frontier’s revenue comes from selling home phone lines. For Frontier to remain viable, the company must attract and keep internet customers. For the last several years, it has failed to do either.

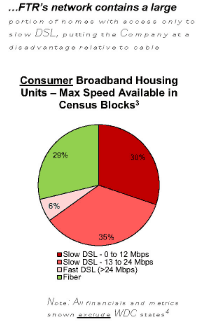

So why would a company like Frontier not immediately hit the upgrade button and start a massive copper retirement-fiber upgrade plan to keep the company in the black? In short, Frontier has survived chronic underinvestment because of a lack of broadband competition. Nearly two million Frontier customers have only one choice for internet access: Frontier. For another 11.3 million, there is only one other choice – a cable company that many detest. Frontier has enjoyed its broadband monopoly/duopoly for at least two decades. So long as its customers have fewer options, Frontier is under less pressure to invest in upgrades.

So why would a company like Frontier not immediately hit the upgrade button and start a massive copper retirement-fiber upgrade plan to keep the company in the black? In short, Frontier has survived chronic underinvestment because of a lack of broadband competition. Nearly two million Frontier customers have only one choice for internet access: Frontier. For another 11.3 million, there is only one other choice – a cable company that many detest. Frontier has enjoyed its broadband monopoly/duopoly for at least two decades. So long as its customers have fewer options, Frontier is under less pressure to invest in upgrades.

Comcast and Charter Communications have begun to compete outside of their respective cable footprints, potentially competing directly head to head for your business, but only if you are a super-sized corporate client.

Comcast and Charter Communications have begun to compete outside of their respective cable footprints, potentially competing directly head to head for your business, but only if you are a super-sized corporate client.

But neither company wants to end their comfortable fiefdoms in the residential marketplace by competing head to head for customers. Companies claim it would not be profitable to install redundant, competing networks, even though independent fiber to the home overbuilders have been doing so in several cities for years. It seems more likely cable operators are deeply concerned about threatening their traditional business model supplying services that face little competition. In the early years, that was cable television. Today it is broadband. Large swaths of the country remain underserved by telephone companies that have decided upgrading their deteriorating copper wire networks to supply residential fiber broadband service is not worth the investment, leaving most internet connectivity in the hands of a single local cable operator. Most cable companies have taken full advantage of this de facto monopoly by regularly raising prices despite the fact that the costs associated with providing internet service have been declining for years.

But neither company wants to end their comfortable fiefdoms in the residential marketplace by competing head to head for customers. Companies claim it would not be profitable to install redundant, competing networks, even though independent fiber to the home overbuilders have been doing so in several cities for years. It seems more likely cable operators are deeply concerned about threatening their traditional business model supplying services that face little competition. In the early years, that was cable television. Today it is broadband. Large swaths of the country remain underserved by telephone companies that have decided upgrading their deteriorating copper wire networks to supply residential fiber broadband service is not worth the investment, leaving most internet connectivity in the hands of a single local cable operator. Most cable companies have taken full advantage of this de facto monopoly by regularly raising prices despite the fact that the costs associated with providing internet service have been declining for years.