Your cable bill is going up… a lot.

Within five years, the average cable television subscription will reach $125 a month, primarily because of rapidly rising sports programming costs that are enriching already wealthy sports teams and players.

Professional and college sports are benefiting from the largesse of sports channels and networks all competing for the rights to televise games. Until a decade ago, those rights typically went to the highest paying broadcast television network. But as traditional cable sports networks like ESPN find themselves competing with more than three dozen other cable networks and regional sports channels, bidders need ever-deeper pockets to stay in the running. With cable customers footing the bill, the sky has been the limit.

Cable companies that routinely complain about runaway inflation in sports programming costs suddenly go silent when they get a piece of the action. Take Time Warner Cable, for example. A substantial amount of the company’s recently announced rate hike they blame on “increased programming costs” comes from networks they own and operate. A network dedicated to just one team – the Los Angeles Dodgers, will cost subscribers slightly less than $5 a month. SportsNet LA was created around Time Warner’s 25-year rights deal to show Dodgers games. The cable company is paying $8.3 billion for the privilege. Another network, dedicated to the Los Angeles Lakers, also costs Time Warner Cable customers $4 a month whether they watch or want the channel or not.

Out east, the Yankees Channel YES costs subscribers around $3.50 a month — a bargain compared to the Dodgers — with prices expected to increase further in the years ahead. ESPN, by far the largest sports network, insists on more than $5 a month from every customer even if they have never watched the network.

Out east, the Yankees Channel YES costs subscribers around $3.50 a month — a bargain compared to the Dodgers — with prices expected to increase further in the years ahead. ESPN, by far the largest sports network, insists on more than $5 a month from every customer even if they have never watched the network.

Every year, prices are rising for sports programming, and fast. The lucrative billions in revenue are now turning up in players’ salaries, provide piles of money to “non-profit” educational institutions with college sports teams, and are inflating the overall value of the teams for their owners. Fans who are looking for platforms where they can place their bets may explore sites like 토토사이트검증 먹튀스팟.

The inflation spiral is accompanied by a framework of entitlement, where owners, players, and schools now expect regular increases in payments to secure television rights. Those costs are passed on directly to every subscriber, because few sports networks will allow themselves to be sold “a-la-carte” only to those who actually want to watch.

With even more sports networks launching on the horizon, the average cable bill that now costs about $90 a month will increase by $35 a month to reach $125 a month within a few years, according to the Los Angeles Times:

The dispute over telecasts of Dodgers baseball games exemplifies the problem with the current setup. Time Warner Cable wants to charge Southern California subscribers slightly less than $5 a month to watch the games on a Dodger channel. Area TV distributors (such as DirecTV, Cox Cable and AT&T U-verse), fearing a consumer backlash, are resisting. If Time Warner and the Dodgers win, it’s a lucrative deal — for them. Not so for those who don’t care to watch. Even Dodger fans, blacked out now, aren’t really winners. The system denies all of us meaningful choices. All subscribers end up subsidizing programming we never watch.

In effect, because of the way channels are bundled, all pay-TV subscribers (roughly 100 million households) are subsidizing sports. The subsidy is substantial. The Pac-12 conference estimates it will receive $3 billion in TV revenue over a 12-year period. For ESPN, it’s much more. If roughly 90% of pay-TV households purchase the bundle that includes ESPN, that network alone will receive just short of $6 billion in revenue in a single year.

That’s a major subsidy, and, given a Cox Cable representative’s estimate that only 15% to 20% of viewers regularly watch sports programming, it’s paid mostly by viewers who neither watch nor wish to subsidize ESPN programming. These viewers swallow the bitter inflationary pill in order to watch other channels in the bundle.

Both college and professional sports teams benefit from the subsidy. The winners include UCLA and UC Berkeley, taxpayer-supported institutions, and USC and Stanford, preeminent private, nonprofit institutions that also benefit from federal money. UCLA alone reportedly received $14.5 million in TV revenue over the last year. Americans are accustomed to college athletic programs that make money, but do we really want these revenues to be generated on the backs of angry consumers who must pay a sports subsidy every time they purchase subscription TV?

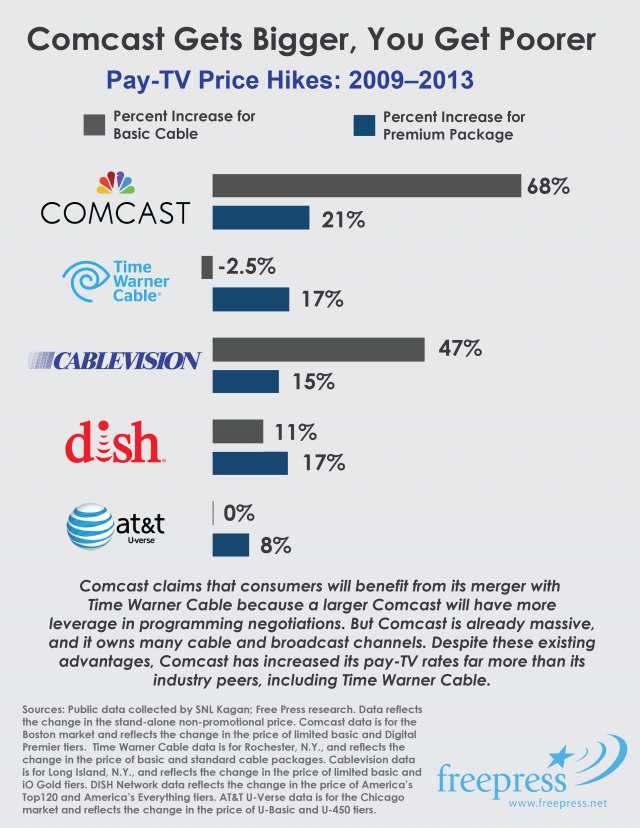

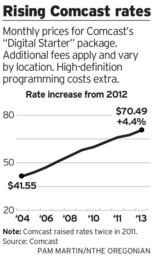

Despite arguing its merger with Time Warner Cable would result in greater discounts for cable programming, America’s largest cable company Comcast is already receiving the best volume discounts available but is not passing the savings on to customers.

Despite arguing its merger with Time Warner Cable would result in greater discounts for cable programming, America’s largest cable company Comcast is already receiving the best volume discounts available but is not passing the savings on to customers.

Subscribe

Subscribe Despite growing competition from Bell’s fiber-to-the-neighborhood service Fibe, now expanding into many of Cogeco’s outer suburban service areas, Cogeco will not negotiate a better deal for customers, preferring to emphasize its customer service and “right-sizing” bundles of services to best meet customer needs.

Despite growing competition from Bell’s fiber-to-the-neighborhood service Fibe, now expanding into many of Cogeco’s outer suburban service areas, Cogeco will not negotiate a better deal for customers, preferring to emphasize its customer service and “right-sizing” bundles of services to best meet customer needs.

Out east, the Yankees Channel YES costs subscribers around $3.50 a month — a bargain compared to the Dodgers — with prices expected to increase further in the years ahead. ESPN, by far the largest sports network, insists on more than $5 a month from every customer even if they have never watched the network.

Out east, the Yankees Channel YES costs subscribers around $3.50 a month — a bargain compared to the Dodgers — with prices expected to increase further in the years ahead. ESPN, by far the largest sports network, insists on more than $5 a month from every customer even if they have never watched the network.