Phillip “The circus is in town” Dampier

Yesterday afternoon I got to experience both the pain of having a tooth pulled and watch Comcast and Time Warner Cable defend its merger for more than three hours before the Senate Judiciary Committee. The Festival of Nonsense from Comcast’s top lobbyist David Cohen and Time Warner Cable’s chief financial officer Arthur Minson hurt more.

Despite the $45 billion dollar deal, the real powers that be couldn’t be bothered to turn up at the hearing. Comcast’s chief executive was nowhere to be found — perhaps he was playing golf with President Obama again. Comcast’s top lobbyist David Cohen showed up instead, wearing an outfit that looked like it was stuffed with cash waiting to fall from his pockets into the hands of his “friends” on Capitol Hill. Cohen is a well-known Democratic money bundler who raised $1.44 million for the president’s reelection campaign in 2011 and 2012, and $2.22 million since 2007. (Obama spent time in Cohen’s Philadelphia home as well, part of a DNC fundraising party.)

Perhaps Time Warner Cable CEO Robert Marcus was unavailable because he was too busy counting the $8.52 million he was paid before agreeing to sell the company. Don’t expect him at the next hearing either, because he is shopping for a bigger safe to hold the $80 million he will receive for agreeing to change Time Warner Cable’s name to Comcast.

The other usual suspects were also missing in action. Not a peep from the major networks or cable programmers at the hearing. Instead, the Senate endured a guy with a golf channel nobody ever heard of using the hearing to try to get his calls returned by Time Warner and a wireless provider who believes his technology is faster than fiber. Sure it is.

Brought to you in part by America’s cable industry.

I suppose it’s also worth mentioning Christopher Yoo – Comcast’s intellectual sock puppet straight out of the cable company’s home town of Philadelphia. He serves at the pleasure of the “Center for Technology, Innovation & Competition” (cough) at the University of Pennsylvania. The “center” is financially supported by the cable industry. David Cohen just happens (by sheer coincidence) to chair the university’s Board of Trustees. Yoo’s testimony could be boiled down to a nod in Cohen’s direction with an affirming, “whatever he said.”

The Cohen and Minson Comedy Hour began with opening statements extolling the virtues of supersizing Comzilla, with dubious claims about its benefits for consumers.

Without laughing, read the following out loud:

“We welcome this opportunity to discuss the proposed transaction between Comcast Corporation (“Comcast”) and Time Warner Cable Inc. (“TWC”), and the substantial and multiple pro-consumer, pro-competitive, and public interest benefits that it will generate, including through competitive entry in segments neither company today can meaningfully serve on its own,” the two companies wrote in their joint opening statement.

Cohen

“Comcast and TWC do not compete for customers in any market – either for broadband, video, or voice services. The transaction will not reduce competition or consumer choice at all. Comcast and TWC serve separate and distinct geographic areas. This simple but critically important fact has been lost on many who would criticize our transaction, but it cannot be ignored – competition simply will not be reduced. Rather, the transaction will enhance competition in key market segments, including advanced business services and advertising.”

To emphasize just how little this merger will impact the current state of non-competition in the broadband marketplace, Comcast repeatedly emphasized you can’t subscribe to a competing cable company today and still won’t tomorrow:

“Consumers in Comcast’s territories cannot subscribe to TWC for broadband, video, or phone services. And TWC customers cannot switch to Comcast. For that reason, this is not a horizontal transaction under merger review standards, and there will be no reduction in competition or consumer choice,” said the written statement.

In other words, since there was no competition between cable companies before, making sure consumers still don’t have a choice is not anti-competitive.

Watch the entire hearing on the Senate Judiciary Committee website.

(The hearing begins at the 24 minute mark.)

Here are some other “benefits” promised by Cohen and Minson:

Post-transaction, Comcast intends to make substantial incremental upgrades to TWC’s systems to migrate them to all-digital, freeing up bandwidth to deliver greater speeds. For example, Comcast typically bonds 8 QAM channels together in its systems, and Comcast’s most popular broadband service tier offers speeds of 25/5Mbps upstream across its footprint. In comparison, TWC bonds 4 QAM channels in nearly half of its systems, and its most commonly purchased service tier offers speeds of 15/1Mbps. Comcast’s fastest residential broadband tier offers speeds of 505/100Mbps; TWC’s current top speeds are 100/5Mbps. Comcast’s investments in the TWC systems will also improve network reliability, network security, and convenience to TWC customers.

Minson

Of course, nothing prevented either company from boosting speeds without a $45 billion merger deal. In fact, Comcast is doing exactly that this week. Marcus’ own revival plan for TWC, dubbed TWC Maxx, promised Time Warner Cable customers would get even faster speeds than Comcast offers most of its customers.

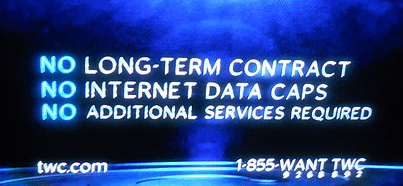

Time Warner Cable now advertises it does not have usage caps on broadband. Comcast cannot say the same, although it tries very hard to tapdance around the matter by calling the 300GB monthly cap spreading into more and more Comcast territories a “data threshold.”

Comcast’s speed upgrades for TWC customers are likely to come with a big catch — an arbitrary usage allowance that limits their usefulness. By the way, that 505Mbps service is available only from Comcast’s extremely limited fiber network that the overwhelming majority of customers cannot get.

The transaction will similarly speed the availability of advanced Wi-Fi equipment in consumers’ homes. The quality of broadband service depends not only on the “last-mile” infrastructure but also the delivery of the signal over the last few yards. Comcast has led the entire broadband industry in rolling out advanced gateway Wi-Fi routers to approximately 8 million households and small businesses, giving these customers faster speeds (up to 270 Mbps downstream as compared to 85 Mbps downstream from the prior generation devices) and better performance over their home and business wireless networks. In contrast, TWC only recently began deploying advanced in-home Wi-Fi routers. With the greater purchasing power and economies of scale resulting from the transaction, Comcast can not only offer TWC customers access to today’s best routers, but also invest in and deploy next-generation router technologies for all of the combined company’s customers.

Comcast doesn’t like to mention that “advanced Wi-Fi” equipment costs customers $8 a month… forever. Comcast is also using it to boost its own Wi-Fi service by sharing it with the neighbors. This merger “benefit” will cost customers almost $100 a year. Customers can do better buying their own equipment and don’t need a merger to make that decision.

Comcast doesn’t like to mention that “advanced Wi-Fi” equipment costs customers $8 a month… forever. Comcast is also using it to boost its own Wi-Fi service by sharing it with the neighbors. This merger “benefit” will cost customers almost $100 a year. Customers can do better buying their own equipment and don’t need a merger to make that decision.

The transaction will give Comcast the geographic reach, economies of scale, customer density, and return on investment needed to massively expand Wi-Fi hotspots across the combined company’s footprint, including in the Midwest, South, and West, particularly in areas like Cleveland/Pittsburgh, the Carolinas, Texas, and California, where there will be greater density and clustering of systems. Our goal is to provide greater Wi-Fi availability that allows the combined company’s customers to access the Internet in more places, more conveniently, and at no additional charge.

Your usage allowance will likely apply to this “free Wi-Fi” that most customers cannot access because they live in an area where neither company offers it now and likely won’t anytime soon.

The transaction will also enable Comcast to invest in network expansions and last-mile improvements that provide an even stronger foundation for innovative applications, including education, healthcare, the delivery of government services, and home security and energy management. And with greater coverage and density of systems, Comcast will also have the ability and incentive to build out and make available interconnection points in more geographic regions. This will be especially beneficial to companies like Google, Netflix, and Amazon, which aggregate massive data traffic when they deliver their own and others’ services to consumers.

For the right price. Nothing precluded Comcast or Time Warner Cable from investing some of their lush profits into improvements for customers. But why bother when your only serious competitor is usually DSL. Investment in broadband networks has declined for years in favor of profit-taking. Making Comcast bigger introduces no new market forces that would provoke it to improve service. In fact, Comcast’s massive size and reach would likely deter would-be competitors from entering a market where Comcast can use predatory pricing and retention offers to keep customers from switching.

For the right price. Nothing precluded Comcast or Time Warner Cable from investing some of their lush profits into improvements for customers. But why bother when your only serious competitor is usually DSL. Investment in broadband networks has declined for years in favor of profit-taking. Making Comcast bigger introduces no new market forces that would provoke it to improve service. In fact, Comcast’s massive size and reach would likely deter would-be competitors from entering a market where Comcast can use predatory pricing and retention offers to keep customers from switching.

Helping people successfully cross the digital divide requires ongoing outreach. To increase awareness of the Internet Essentials program, Comcast has made significant and sustained efforts within local communities. To date, those outreach efforts have included:

- Distributing over 33 million free brochures to school districts and community partners for (available in 14 different languages).

- Broadcasting more than 3.6 million public service announcements with a combined value of nearly $48 million.

- Forging more than 8,000 partnerships with community-based organizations, government agencies, and elected officials at all levels of government.

Cohen does not mention the company planned to offer Internet Essentials earlier than it did, but held it back for political reasons.

“I held back because I knew it may be the type of voluntary commitment that would be attractive to the chairman” of the Federal Communications Commission, Cohen said in a 2012 interview. Comcast’s generosity was limited. It specifically designed its discount Internet program to make it difficult to qualify and protect its regular-priced broadband offerings. The goodwill from handing out Comcast sales brochures and getting free exposure in the media offers little to customers. Comcast also has a way of getting the community-based organizations it “partners” with to advocate for Comcast’s business interests.

“Sometimes we need a kick in the butt.” — Cohen

If only the government got out of the way and approve the merger, Comcast will improve on its already amazing customer service:

Improving the customer experience is a top priority at Comcast. We are investing billions of dollars in our network infrastructure and are developing innovative products and features to make it easier and more convenient for our customers to interact with us. While our satisfaction results are beginning to rise, we know we still have work to do and are laser-focused on continuing to improve our customers’ experiences in a number of ways. Comcast has improved its customer satisfaction ratings significantly. Since 2010, Comcast has increased its J.D. Power’s Overall Satisfaction score by nearly 100 points as a video provider, and close to 80 points in High Speed Data – more than any other provider in our industry during the same period.

Twice nothing is still nothing. Cohen even admitted at the hearing Comcast’s progress at improving customer service is not as rosy as his written testimony might suggest.

“It bothers us we have so much trouble delivering high quality of service to customers on a regular basis,” Cohen said. “Sometimes, we need a kick in the butt.”

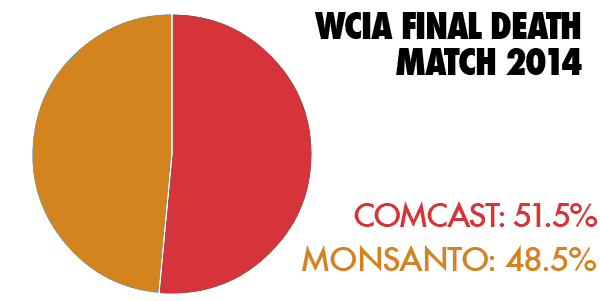

That has never worked before. Comcast has kicked its customers around since at least 2007 when it also promised major customer service improvements that turned out to be figments of a press release. Comcast’s “laser-focused” efforts to improve instead won it the 2014 Consumerist Worst Company in America award this week and more than 100,000 consumers signing petitions vehemently opposing the merger.

Comcast has a long record of improving consumers’ online experiences and working cooperatively with other companies on interconnection, peering and transit.

Just ask any Comcast customer about their Netflix viewing experience lately and how it took a checkbook to improve matters. Ask any online video competitor whether Comcast is a good neighbor when it exempts its own video traffic from its “usage threshold” while making sure to count competitors’ traffic against it.

Just ask any Comcast customer about their Netflix viewing experience lately and how it took a checkbook to improve matters. Ask any online video competitor whether Comcast is a good neighbor when it exempts its own video traffic from its “usage threshold” while making sure to count competitors’ traffic against it.

Comcast also likes to suggest Americans are awash in competitive options for broadband service. Why there is DSL, satellite broadband, fiber, wireless Internet, public libraries, and books.

In fact, Comcast’s filing points to various “competitors” that don’t even exist yet, if they ever will. Comcast suggests Google Fiber is popping up everywhere, despite the fact Google announced it was delaying its fiber rollout in Austin, and most of its latest expansion plans lack firm commitments to deploy and are framed only in the context of opening a dialogue with targeted communities.

Satellite Internet speeds are severely limited and usage-capped. The same is true for exorbitantly expensive mobile broadband. Comparing a $40 unlimited broadband offering from Time Warner Cable to Verizon Wireless’ 4GB for $50 mobile wireless Internet package is silly.

Comcast characterizes the competitive telecom marketplace as a veritable dogfight, but it looks a lot more like a well-executed dog and pony show. Just how rabid are these dogs?

- Verizon’s pit bull zeal to compete has more bark than bite. Verizon Wireless customers can sign up for Comcast or Time Warner Cable service in Verizon stores (woof);

- Comcast’s rottweiler isn’t supposed to get along well with others, but it manages pretty well pitching Verizon Wireless service (grrr).

An hour into the hearing, it was clear there was some bipartisan discomfort with the merger, with Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) leading the charge with pointed questions cutting through Comcast’s government relations fluff.

“I’m against this deal,” Franken concluded. “My concern is that as Comcast continues to get bigger, you’ll have even more power to exercise that leverage — to squeeze consumers.”

Like an orange.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Comcast doesn’t like to mention that “advanced Wi-Fi” equipment costs customers $8 a month… forever. Comcast is also using it to boost its own Wi-Fi service by sharing it with the neighbors. This merger “benefit” will cost customers almost $100 a year. Customers can do better buying their own equipment and don’t need a merger to make that decision.

Comcast doesn’t like to mention that “advanced Wi-Fi” equipment costs customers $8 a month… forever. Comcast is also using it to boost its own Wi-Fi service by sharing it with the neighbors. This merger “benefit” will cost customers almost $100 a year. Customers can do better buying their own equipment and don’t need a merger to make that decision. For the right price. Nothing precluded Comcast or Time Warner Cable from investing some of their lush profits into improvements for customers. But why bother when your only serious competitor is usually DSL. Investment in broadband networks has declined for years in favor of profit-taking. Making Comcast bigger introduces no new market forces that would provoke it to improve service. In fact, Comcast’s massive size and reach would likely deter would-be competitors from entering a market where Comcast can use predatory pricing and retention offers to keep customers from switching.

For the right price. Nothing precluded Comcast or Time Warner Cable from investing some of their lush profits into improvements for customers. But why bother when your only serious competitor is usually DSL. Investment in broadband networks has declined for years in favor of profit-taking. Making Comcast bigger introduces no new market forces that would provoke it to improve service. In fact, Comcast’s massive size and reach would likely deter would-be competitors from entering a market where Comcast can use predatory pricing and retention offers to keep customers from switching.

Just ask any Comcast customer about their Netflix viewing experience lately and how it took a checkbook to improve matters. Ask any online video competitor whether Comcast is a good neighbor when it exempts its own video traffic from its “usage threshold” while making sure to count competitors’ traffic against it.

Just ask any Comcast customer about their Netflix viewing experience lately and how it took a checkbook to improve matters. Ask any online video competitor whether Comcast is a good neighbor when it exempts its own video traffic from its “usage threshold” while making sure to count competitors’ traffic against it. Time Warner Cable has introduced a new marketing message to potential customers, promoting the fact its broadband service has “no data caps.”

Time Warner Cable has introduced a new marketing message to potential customers, promoting the fact its broadband service has “no data caps.”

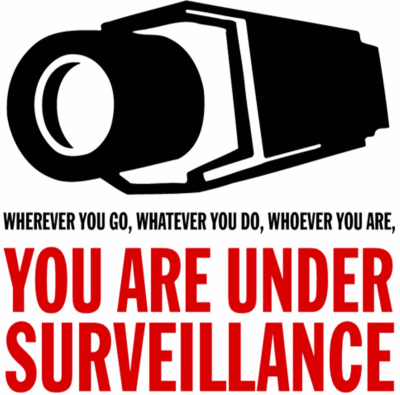

Sometime in the future, your cable company could begin activating built-in RFID or NFC chips inside mobile devices to gather information about a viewers’ presence and mood to deliver customized programming and advertising.

Sometime in the future, your cable company could begin activating built-in RFID or NFC chips inside mobile devices to gather information about a viewers’ presence and mood to deliver customized programming and advertising.