Some of America’s top telephone and cable companies will likely pay little, if any federal taxes as a result of the passage of a Republican-sponsored tax cut plan, while some may also receive generous “refunds” based on depreciation-related expenses and future investments the companies would have made with or without changes to the tax code.

Some of America’s top telephone and cable companies will likely pay little, if any federal taxes as a result of the passage of a Republican-sponsored tax cut plan, while some may also receive generous “refunds” based on depreciation-related expenses and future investments the companies would have made with or without changes to the tax code.

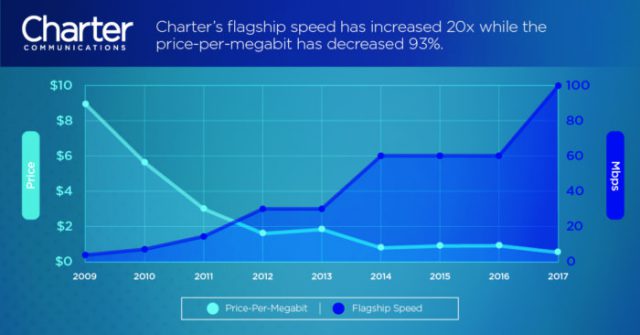

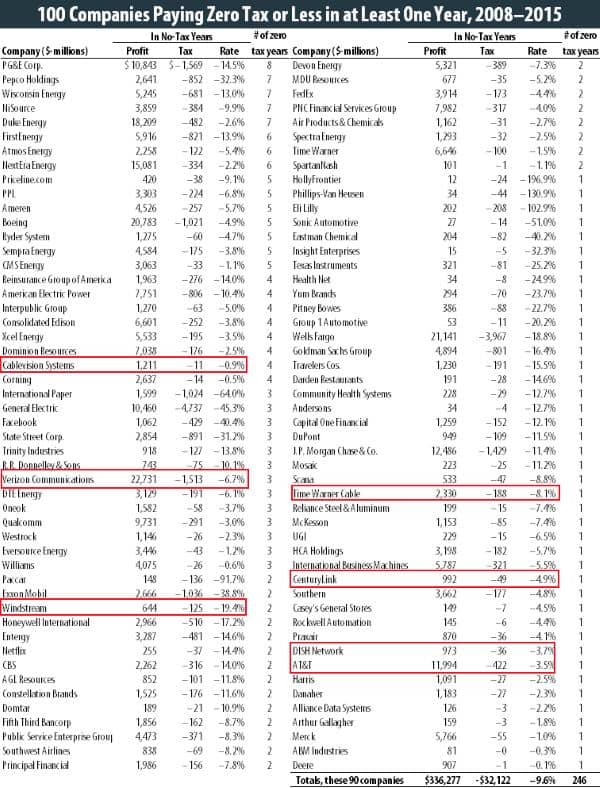

For several years in the last decade, companies with significant infrastructure expenses often did not spend a penny in federal taxes thanks to generous loopholes and incentive programs designed to encourage corporations to invest in new equipment, research, and development. The new Republican-sponsored tax cut is expected to provide a windfall of tax savings for every corporation in the country, but telecom companies are expected to do especially well with a combination of a lower corporate tax rate and the GOP’s failure to fulfill a commitment to close many of the tax loopholes and incentives that were originally designed to get companies spending during the Great Recession.

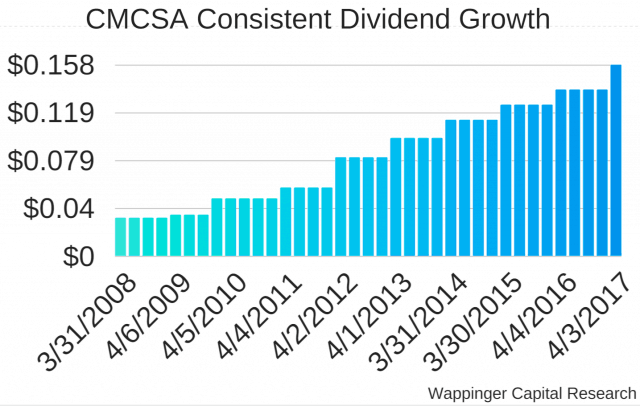

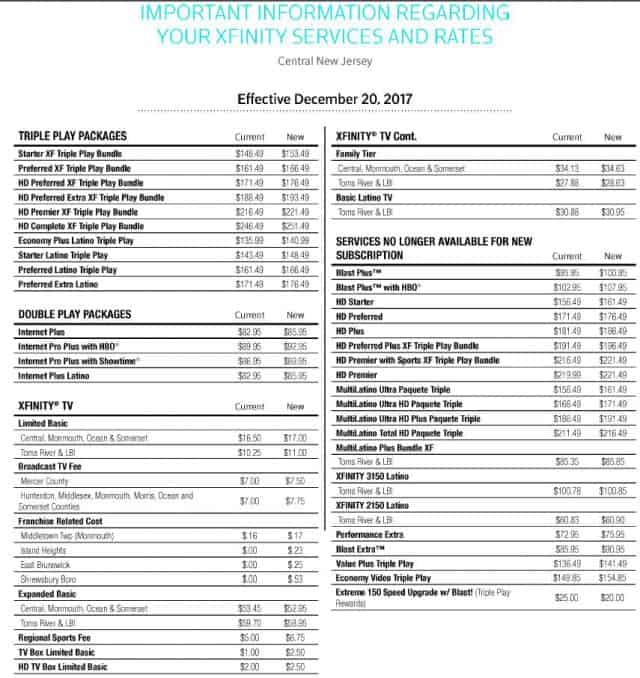

No provider has promised customers lower rates as a result of the billions of additional dollars the companies are expected to keep in the bank starting next year. In fact, there are early signs that much of the anticipated windfall will be returned to shareholders in the form of increased dividend payouts and accelerated share buyback schemes that reduce the number of shares available for sale, boosting both the sale price of the stock and executive bonus compensation tied to the price performance of the stock.

Despite that, companies including AT&T and Comcast are cranking up their PR machines to get on the good side of the Trump Administration, suggesting the new tax cuts will directly benefit middle class employees at both companies.

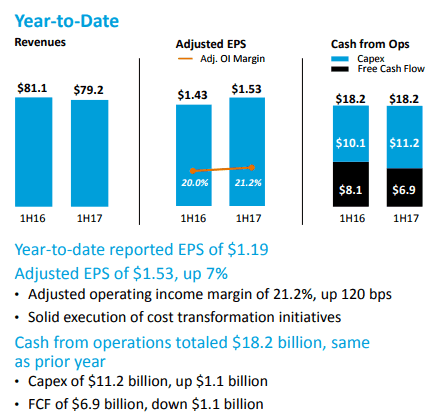

AT&T’s capex increased $1.1 billion to $11.2 billion for the first six months of 2017 without the tax cut legislation.

AT&T announced it would pay a one-time $1,000 bonus to its workers and invest an additional $1 billion in network upgrades as a direct result of the tax cuts.

However, a closer look reveals AT&T’s commitments to boost compensation came not as a result of the tax cut but instead from nearly a year of hard negotiations with the Communications Workers of America (CWA), one of the biggest unions representing AT&T workers.

The CWA argued that AT&T needed to follow-through on the Republican Party’s promise that passage of the tax cuts would result in higher wages for the middle class.

“Republicans, including the president, said the average household would get $4,000 under this tax plan,” CWA spokesperson Candice Johnson told The Daily Beast. In November, CWA officials began to demand $4,000 raises for AT&T workers promised by the GOP. “This bonus came out of that conversation. It’s a start, and we’re going to keep holding our leaders accountable.”

Instead of $4,000 more a year for AT&T workers as a result of the tax cut bill, the union’s influence achieved a $1,000 one time bonus and an average salary bump of 10.1%. Without pressure from the union, many AT&T employees and union officials believe AT&T would have offered little, if anything to its employees as a result of the tax cut.

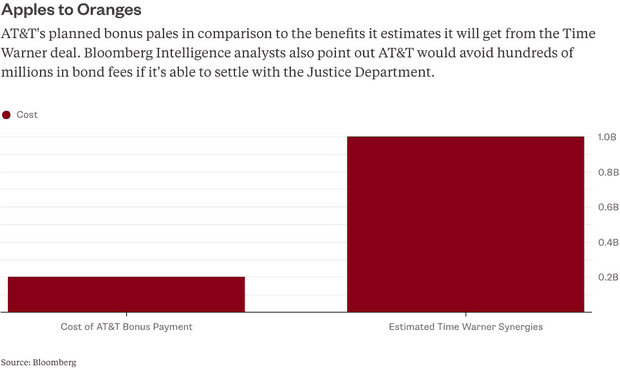

AT&T’s Christmas Bonus will cost the company a fraction of the amount it risks losing if its $109 billion merger deal with Time Warner, Inc., does not survive an antitrust review by the Justice Department and the courts. The Justice Department announced its opposition to the merger. The connection between AT&T’s press release, which plays into the Trump Administration’s talking points about the tax cut law, and AT&T’s need for a friendlier response to its merger deal by administration officials, was not lost on Crane’s Chicago Business:

By now, companies have learned the art of crafting the type of upbeat, largely symbolic press releases our president loves, with enough big numbers to get them on the White House’s good side. If this time around that also means some extra money in workers’ pockets, all the better. But some of these announcements come across as more gimmicky than others, and it’s not hard to wonder if there are also other motives at work.

AT&T is angling to overcome regulatory objections to its $109 billion merger with Time Warner Inc. and either way, needs to invest in the U.S. to build out its fiber-optic cable and 5G networks. Analysts estimate AT&T’s net income will be close to $14 billion this year.

AT&T’s commitment to spend up to $1 billion additional dollars next year as a direct result of the tax cut is recycled old news, critics charge, because AT&T previously announced the same $1 billion commitment in early November. Regardless, the extra spending is a small fraction of AT&T’s overall capex budget.

In 2016, at the height of so-called “investment-killing net neutrality,” AT&T exceeded its 2016 capex forecast, spending $22.9 billion — $900,000 more than it expected. In 2017, AT&T announced it expected to spend $22 billion again this year, primarily on its wireless network and wired business solutions. The other major former Baby Bell – Verizon Communications, spent $17.1 billion in 2016 and expected to spend up to $17.5 billion this year.

AT&T’s promise to spend an additional $1 billion is a token amount, especially when considering the tax cut savings likely to be won by phone companies like AT&T and Verizon. From 2008-2015, AT&T paid an effective federal tax rate of just 8.1%, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. It will pay considerably less under the Republican tax law, potentially saving the company billions. During the same period, Verizon paid absolutely zero federal taxes during many of those years, and in fact won a refund from the IRS because of network investments and depreciation-related savings. Because the GOP did not close many of the corporate loopholes the politicians initially promised would be ended, many telecom companies could once again pay little, if any federal tax, and may secure hefty refunds.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy

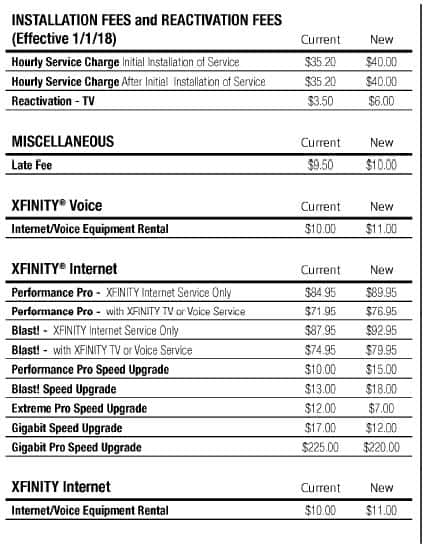

Comcast’s $1,000 Christmas Bonus and $50 Billion Spending Commitment

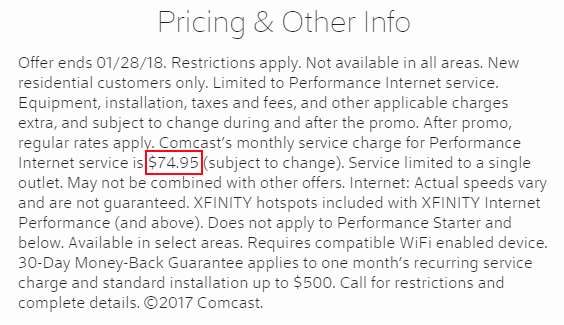

Not to be outdone, Comcast has also promised a $1,000 one time Christmas bonus for its employees as a result of the passage of the GOP tax measure, along with a commitment to spend $50 billion on its business over the next five years:

Based on the passage of tax reform and the FCC’s action on broadband, Brian L. Roberts, chairman and CEO of Comcast NBCUniversal, announced that the company would award special $1,000 bonuses to more than 100,000 eligible frontline and non-executive employees. Roberts also announced that the company expects to spend well in excess of $50 billion over the next five years investing in infrastructure to radically improve and extend our broadband plant and capacity, and our television, film and theme park offerings.

Roberts

Comcast’s spending on its theme parks acquired from NBCUniversal has been especially bullish, with Roberts announcing earlier this year nearly $2 billion in spending in 2017. In fact, Comcast’s capex spending has trended higher year after year, especially after its acquisition of NBCUniversal. In 2014, the company spent $7.2 billion on capital investments. In 2015, as net neutrality rules took effect, Comcast raised investments to $8.1 billion. In 2016, the capex budget fell slightly to $7.597 billion in 2016, but was forecast to reach $8.445 billion in 2017. Ars Technica reports that from the fourth quarter of 2016 through the third quarter of 2017, Comcast spent $9.4 billion on capital investments.

Much of that spending has been to pay for its X1 set-top box, theme park upgrades, and scaling up its broadband infrastructure to handle faster internet speeds. Earlier in 2017, Comcast also boosted its commitment to spend billions on buying back shares of its own stock, which will benefit shareholders and company executive compensation plans.

As the industry marches towards fiber upgrades and DOCSIS 3.1 deployment, Comcast’s capex forecast without the tax cuts would like come very close to Roberts’ $50 billion estimate over the next five years, assuming the company spent a reasonable average of close to $10 billion annually. Roberts said he “expects” spending at that level, but did not commit to it formally, so there is no penalty for overestimating investment numbers.

AT&T earlier noted predictions about capital investments always relate to actual need at the time and the company doesn’t spend money it does not need to spend.

“There is no reason to expect capital expenditures to increase by the same amount year after year,” AT&T said at the time. “Capital expenditures tend to be ‘lumpy.’ Providers make significant expenditures to upgrade and expand their networks in one year (e.g., perhaps because a new generation of technology has just been introduced), and then focus the next year on signing up customers and integrating those new facilities into their existing networks, and then make additional capital expenditures later, and so on.”

But there are political upsides to making no-strings-attached investment predictions anyway.

Comcast’s share repurchase program also allows the company to boost dividend payouts to shareholders.

Issuing a favorable press release that dovetails with the Trump Administration’s tax cut plan could buy Comcast goodwill from the administration as the company faces calls from Congress to extend merger deal conditions and restrictions on its 2011 acquisition of NBCUniversal. Those conditions are scheduled to expire in September 2018.

Jon Brodkin notes that telecom companies frequently tie their spending plans to regulatory matters going in their favor:

When ISPs are asking the government for a specific policy change—such as the repeal of a regulation or a tax break—they are quick to claim that the desired policy will lead to more investment.

AT&T, for example, announced last month that it would invest “an additional $1 billion” if Congress passes tax reform. With the tax reform now passed by Congress, AT&T said yesterday that it will move ahead with that $1 billion increase.

But neither one of those AT&T announcements said what the exact level of investment would have been if the tax bill wasn’t passed.

And in 2010, AT&T told the FCC that capital expenditures are based on technology upgrade cycles rather than government policy. At the time, AT&T was asking the FCC for a favor—the company wanted a declaration that the wireless market is competitive, a finding that can influence how the FCC regulates wireless carriers.

Subscribe

Subscribe

The 2015 rules were intended to give consumers equal access to web content and prevent broadband providers from favoring their own content. Pai proposes allowing those practices as long as they are disclosed.

The 2015 rules were intended to give consumers equal access to web content and prevent broadband providers from favoring their own content. Pai proposes allowing those practices as long as they are disclosed.