A stack of revealing company documents obtained by the New York State Attorney General’s office suggest top executives at Time Warner Cable were aware the company was intentionally misleading customers and the Federal Communications Commission with broadband performance promises the company knew it could not keep.

Portions of the documents were made part of the public record as part of a lawsuit filed today by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman against Charter Communications and Time Warner Cable (now a subsidiary of Charter). The suit alleges that Time Warner Cable systematically and intentionally underdelivered on its commitments to improve broadband service and oversold its network in New York, causing widespread speed slowdowns and performance issues.

The 87-page complaint reveals Time Warner Cable woefully underinvested in its network, leaving customers with poor internet speeds and obsolete cable modems the company leased to customers for up to $10 a month. But a careful review of other statements from company executives also undermines the cable industry’s arguments for data caps, paid interconnection agreements with content providers, the lack of need for Net Neutrality, and the overuse of marketingspeak that allows cable operators to promise speeds they know they cannot deliver.

This two-part Stop the Cap! report analyzes the lawsuit and its offer of proof and will take you beyond the headlines of the legal action against Charter Spectrum/Time Warner Cable and explore some of the cable company’s confidential emails, memos, and meetings.

The documents reveal a lot of ordinarily highly confidential data points about how many subscribers share a Time Warner Cable internet connection, how many deficient and obsolete cable modems are still in the hands of customers, and how the pervasive need to avoid investing in network upgrades caused executives to repeatedly reject spending requests while approving rate increases.

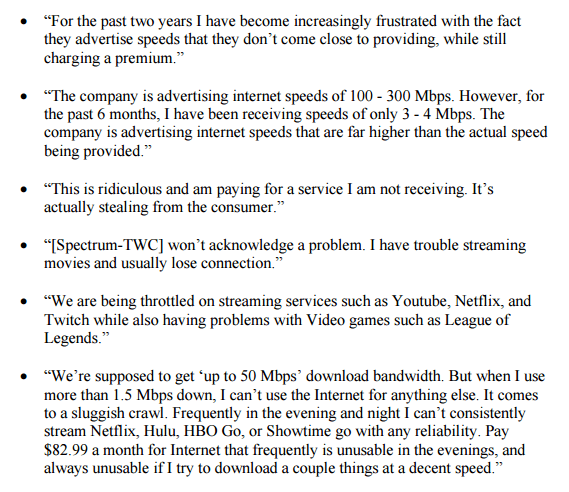

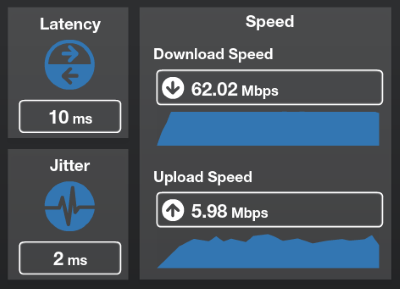

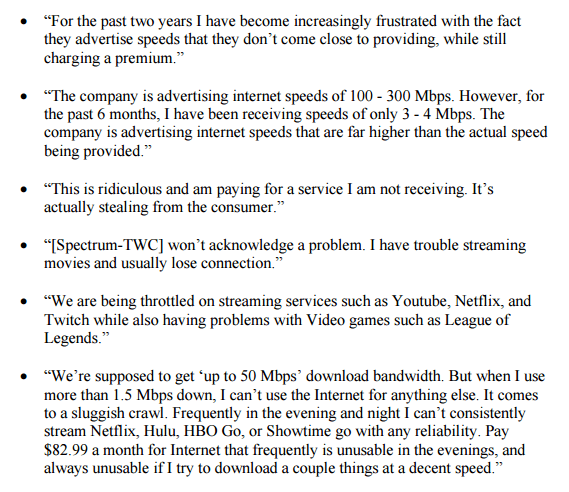

Typical complaints from Spectrum-TWC customers sent to N.Y. Attorney General’s office.

How Spectrum-Time Warner Cable Brings You Broadband Service

N.Y. Attorney General Eric Schneiderman

Time Warner Cable was one of New York’s most important communications companies. At least 2.5 million New York households — one out of three — get internet access from what is now known as Charter Spectrum. Every broadband customer belongs to a “service group” made up of a number of your neighbors who share the same internet bandwidth. In February 2016, the average Spectrum-TWC service group in New York had about 340 subscribers. The range varied widely in practice, from as few as 32 customers to as many as 621 subscribers belonging to the same group. The fewer the number of customers, the less chance they will encounter a traffic-related slowdown caused by using the internet at the same time. For those congested service groups that do, broadband speeds begin to drop, sometimes precipitously.

The amount of total collective speed available to each service group depends on how much bandwidth the cable operator sets aside for broadband. For the last several years, Time Warner Cable typically reserved eight channels of about 38Mbps each for every neighborhood service group. That is equivalent to about 304Mbps — about the maximum speed one Time Warner Cable Maxx customer can get today. If four customers with 50/5Mbps service decided to “max out” their connection each evening, the remaining 336 customers in the service group would get to collectively share about 104Mbps. If six customers did that, the remaining 334 customers would be left with sharing 4Mbps.

Cable operators have always bet customers won’t be online all at the same time. But as internet usage, particularly online video, has grown, customers are increasingly spending primetime hours of 7-11pm streaming high bandwidth video instead of sitting in front of the television. If a large number of customers in a service group purchasing 15/1Mbps service from Time Warner Cable happened to be viewing HD video at the same time, the speed in that neighborhood could drop to as low as 1Mbps, a far cry from what customers were paying to receive.

Time Warner Cable customers that used to experience nightly slowdowns were told “your node is congested” to explain why speeds were dropping. The engineers that developed the cable broadband standard we know today as DOCSIS, envisioned that upgrades or “node splits” would be periodically required to deal with customer growth and increased traffic. Newer DOCSIS standards also give providers the option of enlarging the amount of shared bandwidth by adding additional channels. In the past, Time Warner Cable performed node splits, dividing up congested neighborhoods into multiple service groups. But with the advent of DOCSIS 3 and 3.1, Time Warner Cable also began expanding the number of channels devoted to broadband, enlarging the amount of shared bandwidth available to customers. Unfortunately for customers, Time Warner Cable was among the slowest of the nation’s cable operators to adopt this strategy.

Delivering Slow Speeds for High Prices

As a result of Time Warner Cable’s lack of investment, the company had to manage its bandwidth limitations in other ways. The documents from the recent lawsuit helped adds to our knowledge of how the company tried and often failed to manage the problem:

As a result of Time Warner Cable’s lack of investment, the company had to manage its bandwidth limitations in other ways. The documents from the recent lawsuit helped adds to our knowledge of how the company tried and often failed to manage the problem:

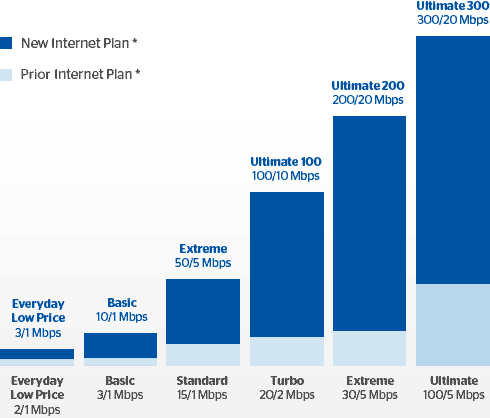

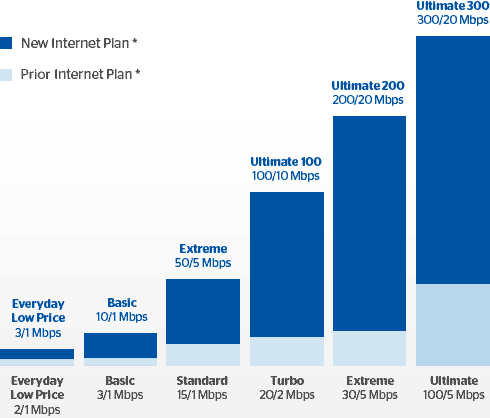

- It avoided regularly increasing internet speeds for its customers. Time Warner Cable customers in most cities were limited to a maximum of 50/5Mbps until the Maxx upgrade program began. Other cable operators were selling speeds several times faster, but Time Warner risked a handful of internet enthusiasts utilizing faster available speeds to consume the bandwidth available to the neighborhood service group. Slower speeds mean fewer upgrades.

- It advertised speeds and performance company engineers and executives admit in confidential documents they could not consistently deliver (or deliver at all in some instances).

- It continued to rely on outdated and obsolete cable modems that severely limit subscribers’ speed, regardless of what level of service the customer subscribed to.

- It avoided network investments for budgetary reasons, even when severely congested neighborhoods exceeded 80-90% usage of all available bandwidth, causing noticeable performance problems for customers.

The lawsuit alleges Time Warner Cable consistently sold internet speed tiers that did not or could not deliver the advertised speeds to consumers. The lawsuit points to three reasons why customers don’t get the speeds they paid for:

Deficient Equipment: Spectrum-TWC leased older-generation, single-channel modems despite knowing that such modems were, in its own words, not “capable of supporting the service levels paid for.” Over the same period, Spectrum-TWC also leased older generation wireless routers to subscribers despite knowing that these routers would prevent them from ever experiencing close to the promised speeds over wireless connections.

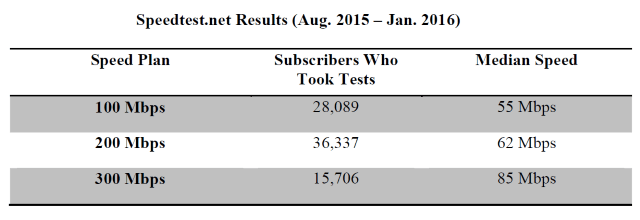

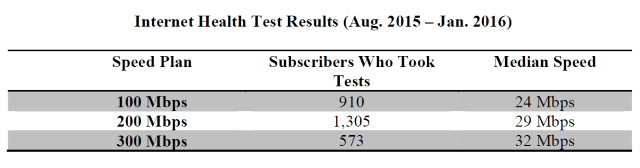

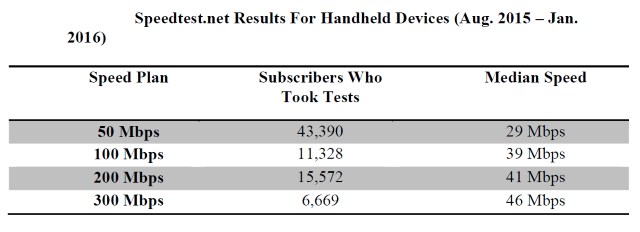

Congested Network: Spectrum-TWC failed to allocate sufficient bandwidth to subscribers by reducing the size of its service groups or increasing the number of channels for its service groups. These network improvements would have enabled subscribers to achieve the fast Internet speeds that they paid for. Results from three independent Internet speed measurements confirmed that Spectrum-TWC consistently failed to deliver the promised speeds to subscribers on its high-speed plans.

Limitations of Wireless: Spectrum-TWC misled subscribers by assuring them that they could achieve the same Internet speeds through wireless connections as with wired connections despite knowing that accessing the Internet using wireless routers would sharply reduce the Internet speeds a subscriber would experience

A key goal for Time Warner Cable executives was to push consumers into broadband upgrades that increased the average revenue they receive from each of their customers. A 2013 internal company presentation called broadband upselling a “strategic pillar” to “capture premium pricing.” If customers endured pushy sales pitches, it may have been because the company tied customer service representative compensation to increasing monthly revenue received from subscribers. If the representative sold you more, they earned more.

Although it sounded good on the surface, internal company documents also show there was pushback from company employees who feared aggressive sales pitches would only further alienate customers.

“Our customers NEED to be put into the proper packages so that we are conducting business with integrity,” wrote one employee in a presumably anonymous employee survey. “It seems as if this is a hustlers job trying to out hustle everyone else trying to make the most money WE can and not doing the right thing . . . By operating like this, customers laugh at our integrity as a company.”

Time Warner Cable Accused of Supplying Obsolete Cable Modems at Prices Up to $10 a Month

Your speed: as slow as 20Mbps

Assuming a customer did upgrade their internet speed, the Attorney General alleges at least 900,000 of those customers were given older generation single-channel DOCSIS 1 and DOCSIS 2 cable modems the company knew were incapable of delivering the speed the customer signed up for. Even worse, the company began charging monthly fees up to $10 a month for equipment the rest of the cable industry deemed obsolete.

A February 2015 email written by the former head of corporate strategy suggests senior corporate management knew they were selling broadband plans to customers that would never perform as advertised.

“The effective speeds we are delivering customers in a 20Mbps tier when they have a DOCSIS 2 modem is meaningfully below 20Mbps,” the email read.

The following month a company engineer sent email explaining the company’s network utilization targets would result in customers using older single-channel modems receiving speeds below 10Mbps during peak utilization times, even if they paid for 50Mbps or faster service available in some markets. The engineer recommended only allowing customers subscribed to internet speeds below 10Mbps to have a single channel modem if absolutely necessary.

A year later, Time Warner Cable executives admitted to the Office of the Attorney General of New York that customers with internet speeds of 20Mbps or higher needed a DOCSIS 3 modem. But during that same month, the cable company leased DOCSIS 2 modems to over 185,000 customers on plans of 20Mbps or higher, for $10 a month. Even worse, almost 800,000 New Yorkers subscribed to 20Mbps or higher speed plans with a deficient modem for three months or longer. And still worse, despite a company directive issued in June 2012 to remove DOCSIS 1 modems from its network, over 100,000 New Yorkers were still leasing a first generation and long obsolete cable modem for three months or longer, again for the same $10 a month. The Attorney General alleges the company knew these subscribers would not get the internet speeds their plans promised and continued to supply deficient equipment for years anyway.

Rate Hikes Yes, Spending Money on Urgent Equipment Upgrades No

DOCSIS 2 modems are largely obsolete, but not at Time Warner Cable.

As customers endured near-annual rate hikes on broadband service, Spectrum-Time Warner Cable refused to launch a plan to recall and replace obsolete cable modems because it was beyond the company’s “capital ability.”

This finding came in response to a confidential June 2013 presentation that included a startling admission: 75% of the cable modems connected to customers with Time Warner Cable’s Turbo (20Mbps) internet plan were non compliant. “DOCSIS 2 modems are still being deployed due to budget constraints,” the presentation stated. An alternate plan suggested postcards be sent to affected customers offering to replace their modems if they returned them because of the speed problems those customers experienced. That plan didn’t get far either.

The Attorney General calls the company’s decision a “self-serving” financial move when it rejected its own engineers’ recommendations to swap modems.

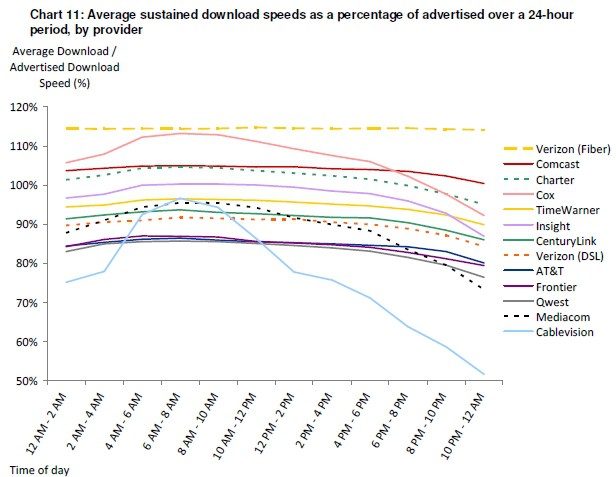

In 2013, company officials did begin prioritizing replacing the modems of a select group of their customers — those volunteering for the FCC’s ongoing Sam Knows broadband speed test program, designed to verify ISP performance. Realizing Time Warner’s speed rankings would be in jeopardy if panelists were still using DOCSIS 2 modems, it made a deal with the FCC to have the agency temporarily exclude slower speed results obtained from customers with DOCSIS 2 modems until they were replaced. Customer Service Representatives were instructed to treat all FCC panelists with “VIP treatment” and provide them with the “best in class devices.” (Full disclosure: Stop the Cap! is a broadband customer of Spectrum-Time Warner Cable and serves as a FCC/Sam Knows panelist.) Spectrum-TWC promised after those customers were upgraded, all others with older equipment would receive replacements as well, a commitment the Attorney General claims the cable company broke.

Even after Time Warner Cable launched its Maxx upgrade program, offering speeds up to 300Mbps, the cable company was still dealing with a sizable number of customers still using DOCSIS 2 modems that could not deliver anything beyond 20Mbps. In 2014, the company promised it would supply new modems to all subscribers with older equipment at no charge. An experimental “Ship to All” plan would have automatically sent the equipment to every affected customer. Management rejected the program as too expensive and replaced it with a “Raise Your Hand” plan that required customers to self-identify obsolete equipment, contact customer service and wait through long hold times or go to the inconvenience of visiting a Time Warner Cable store. In the notice to subscribers, Time Warner never disclosed the most important reason they needed a new modem — without it they would receive one-tenth or less of the speeds they paid to receive. Customers who failed to return their DOCSIS 2 modems in good condition were also penalized with an unreturned/damaged equipment fee, even though the equipment is now deemed obsolete across the industry.

Company officials admitted internally that “Raise Your Hand” was a plan destined to fail, with large numbers of customers not bothering to take the bureaucratic steps needed to exchange modems. Customers in upstate New York received no notification at all. It was a financial win for the company, which collected $10 lease payments on obsolete equipment it did not have to spend any money to replace. The company celebrated the savings, noting in a January 2015 internal presentation “[c]hanging the Maxx [Ship to All] approach to a Raise Your Hand approach (65% of subscribers take an active swap, with passive swaps for the balance) helped us reduce our capital budget by $45 [Million].” Later in 2015, the company internally reported the savings were even greater than expected — only 25% of customers responded to the offer to replace their modems.

New York’s Secret 20Mbps Speed Cap

For reasons unknown, Time Warner Cable also quietly began secretly locking down obsolete DOCSIS 2 cable modems with a speed cap of 20Mbps while not informing customers or customer service that the account should not have or be sold a higher speed plan. Nevertheless, Spectrum-TWC continued to charge customers with DOCSIS 2 modems as much as $70 a month for 100Mbps internet access that would never exceed 20Mbps.

Wi-Fi Woes

Time Warner Cable Maxx speeds don’t always do well on Wi-Fi.

Spectrum-TWC’s former vice president of customer equipment observed in an October 16, 2014 internal email to senior colleagues that “we do not offer a [device] today that is capable of the peak Maxx speed of 300Mbps via wireless. Generally a customer connecting via wireless will receive less than 100 Mbps,” using the 802.11n wireless routers that Spectrum-TWC leased to subscribers.

This fact of life affected 4 out of every 5 Time Warner Cable Maxx customers subscribed to 200 and 300Mbps plans who leased a Wi-Fi equipped cable modem from Spectrum-TWC. As of February 2016, that meant over 250,000 New York customers were paying for premium internet speeds they would never get over the supplied 802.11n wireless router. Customers were never informed. But company executives were, and as a result, the executive told his colleagues that “we are going to experience a mismatch between what we sell the customer and what they actually measure on their laptop/tablet/etc.”

A separate Spectrum-TWC technical document discussing wireless connectivity, dated January 2015, concluded that “[i]n a real world scenario, most [802.11n] adapters will produce speeds of 50-100Mbps.”

In fact, a Spectrum-TWC internal presentation, dated June 12, 2014, recommended that the company deploy devices with newer generation 802.11ac wireless routers to all subscribers on speed tiers of 200Mbps or higher because such routers came closer to delivering the promised speed. Spectrum-TWC rejected that recommendation, again for financial reasons.

Coming up tomorrow… advertising faster speeds or broken promises, company executives tell the truth about bandwidth costs, how to grossly manipulate the FCC’s speed tests, throttling your favorite websites for bigger profits, and hassling online game fans.

The FCC order approving the merger deal was hardly onerous, requiring Charter to compete head-to-head for customers in places the company can choose itself. Lawmakers eliminated exclusive cable franchise agreements years ago, but established major cable operators like Charter have gone out of their way to avoid competing in areas that already receive cable service. While Wheeler may have hoped some of that competition would be directed against fellow cable companies, Charter CEO Thomas Rutledge quickly made clear to investors and the FCC Charter would continue to avoid direct cable competition, instead promising to expand service into non-cable areas that already get DSL service from the phone company or no broadband at all.

The FCC order approving the merger deal was hardly onerous, requiring Charter to compete head-to-head for customers in places the company can choose itself. Lawmakers eliminated exclusive cable franchise agreements years ago, but established major cable operators like Charter have gone out of their way to avoid competing in areas that already receive cable service. While Wheeler may have hoped some of that competition would be directed against fellow cable companies, Charter CEO Thomas Rutledge quickly made clear to investors and the FCC Charter would continue to avoid direct cable competition, instead promising to expand service into non-cable areas that already get DSL service from the phone company or no broadband at all. Rutledge’s clear views about Charter’s expansion plans apparently never made it to the American Cable Association, a cable industry lobbying group that defends the interests of independent and smaller cable operators. Despite Rutledge’s public statements, the ACA and its members are afraid Charter could expand on their turf anyway, potentially forcing small cable operators to compete with the same level of service Charter offers. The horror.

Rutledge’s clear views about Charter’s expansion plans apparently never made it to the American Cable Association, a cable industry lobbying group that defends the interests of independent and smaller cable operators. Despite Rutledge’s public statements, the ACA and its members are afraid Charter could expand on their turf anyway, potentially forcing small cable operators to compete with the same level of service Charter offers. The horror. The real goal here is to minimize direct competition at all costs. The FCC’s deal conditions already included the need for more rural broadband expansion. Wheeler’s second goal was to introduce a new model — cable company competing against cable company — fighting for new customers by offering consumers better service and pricing. The existence of such competition would belie the industry’s claim that cable overbuilds and head-to-head competition is uneconomical. Wildly profitable, perhaps not, but certainly possible. Historically, the traditional way cable operators dealt with the few instances of direct cable competition was to buy them out to put them out of business. Rutledge was certainly thinking along those lines when he complained that the FCC’s order to compete did not include permission to eventually devour its competitor, effectively making competition go away.

The real goal here is to minimize direct competition at all costs. The FCC’s deal conditions already included the need for more rural broadband expansion. Wheeler’s second goal was to introduce a new model — cable company competing against cable company — fighting for new customers by offering consumers better service and pricing. The existence of such competition would belie the industry’s claim that cable overbuilds and head-to-head competition is uneconomical. Wildly profitable, perhaps not, but certainly possible. Historically, the traditional way cable operators dealt with the few instances of direct cable competition was to buy them out to put them out of business. Rutledge was certainly thinking along those lines when he complained that the FCC’s order to compete did not include permission to eventually devour its competitor, effectively making competition go away.

Subscribe

Subscribe

In the summer of 2014, Time Warner Cable had a problem. For three years, the Federal Communications Commission had been issuing reports about the quality of broadband service from the nation’s largest internet service providers. The raw data collected by about 800 subscribers of Time Warner Cable who volunteered to participate in the project began to worry executives because it showed their broadband service was oversold in certain large cities and was no longer capable of consistently achieving advertised speeds. Even worse, the company’s congestion problems threatened to lower Time Warner Cable’s internet performance score at the FCC.

In the summer of 2014, Time Warner Cable had a problem. For three years, the Federal Communications Commission had been issuing reports about the quality of broadband service from the nation’s largest internet service providers. The raw data collected by about 800 subscribers of Time Warner Cable who volunteered to participate in the project began to worry executives because it showed their broadband service was oversold in certain large cities and was no longer capable of consistently achieving advertised speeds. Even worse, the company’s congestion problems threatened to lower Time Warner Cable’s internet performance score at the FCC.

In 2013, a Time Warner Cable executive recognized the company’s practice of limiting company-financed expansion of their upstream connections with the rest of the internet would have serious implications for their own speed test scores, because customers were encountering nightly slowdowns on popular websites like YouTube caused by overcongested connections. Company executives feared customers participating in the Sam Knows/FCC program would soon reveal Time Warner Cable’s internet speeds were beginning to suffer some of the same peak usage problems Cablevision was encountering in 2011. The executive’s solution? Temporarily expand upstream connections just long enough to protect Time Warner Cable’s broadband speed scores:

In 2013, a Time Warner Cable executive recognized the company’s practice of limiting company-financed expansion of their upstream connections with the rest of the internet would have serious implications for their own speed test scores, because customers were encountering nightly slowdowns on popular websites like YouTube caused by overcongested connections. Company executives feared customers participating in the Sam Knows/FCC program would soon reveal Time Warner Cable’s internet speeds were beginning to suffer some of the same peak usage problems Cablevision was encountering in 2011. The executive’s solution? Temporarily expand upstream connections just long enough to protect Time Warner Cable’s broadband speed scores:

As a result of Time Warner Cable’s lack of investment, the company had to manage its bandwidth limitations in other ways. The documents from the recent lawsuit helped adds to our knowledge of how the company tried and often failed to manage the problem:

As a result of Time Warner Cable’s lack of investment, the company had to manage its bandwidth limitations in other ways. The documents from the recent lawsuit helped adds to our knowledge of how the company tried and often failed to manage the problem:

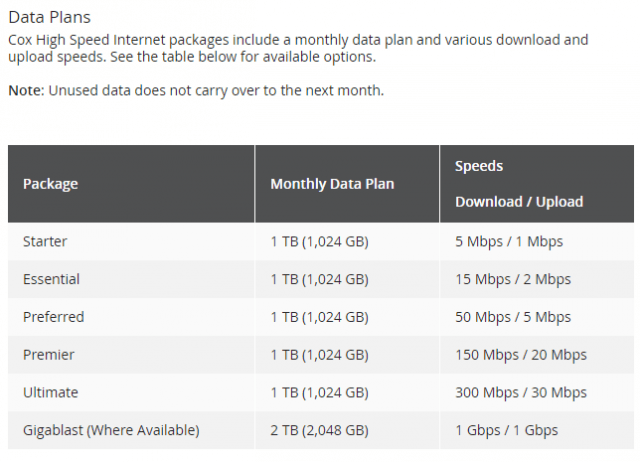

In an effort to keep up with Comcast, Cox Communications has quietly expanded its internet overcharging scheme to customers in Arkansas, Connecticut, Kansas, Omaha, Neb, and Sun Valley, Ida. (perhaps the only community that can afford Cox’s threatened overlimit fees). Cox’s customers have noticed and told DSL Reports about the

In an effort to keep up with Comcast, Cox Communications has quietly expanded its internet overcharging scheme to customers in Arkansas, Connecticut, Kansas, Omaha, Neb, and Sun Valley, Ida. (perhaps the only community that can afford Cox’s threatened overlimit fees). Cox’s customers have noticed and told DSL Reports about the

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment).”

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment).”