Phillip “I Shop Online” Dampier

Last week, JCPenney launched their nationwide redemption tour, apologizing to millions of ex-customers that fled the former retail giant, begging them to come back.

It took over a year for JCPenney to get the message that “disciplining” and “re-educating” customers to accept the wisdom of everyday higher prices with few sales and almost no coupons was hardly the door-busting success “miracle worker” CEO Ron Johnson originally had in mind. The ex-Apple executive was rewarded a $52.7 million signing bonus to take over JCPenney’s tired leadership and in return he dragged sales down 28.4% from the year before, with same store sales down 32%. Johnson’s new vision also steamrolled one-third of JCPenney’s online business.

The day those results became known, he confidently showed Wall Street he did not dwell in the reality-based community: “I’m completely convinced that our transformation is on track!” (For Kohl’s benefit anyway.)

Johnson also believed in a “less is more” philosophy in human resources, overseeing layoffs of 13 percent of the company’s workforce last April, with another 350 let go in July.

Despite the fact his all-new, rebooted vision of JCPenney was about as popular as bird flu, he stayed, even as customers and employees didn’t.

It wasn’t that the company didn’t know customers had a problem with all this. Many complained about the radical, unwanted changes at JCPenney, particularly middle-aged professional women representing one of the stores’ most important business segments. Company executives simply didn’t listen.

A year later, some of the same analysts that cheered JCPenney’s crackdown on discounting now wonder if the company will survive 2013. Many fretted about the real possibility the last customer to brave the “new era” of JCP might forget to turn the lights out when they left for good. Others were mostly furious the board let Johnson go.

Despite the tragic consequences, the conventional wisdom on Wall Street remains: Alienating customers with a revamp nobody asked for and “everyday pricing” designed to boost profits every day was not the problem, how Johnson implemented the strategy was. He just didn’t educate customers enough.

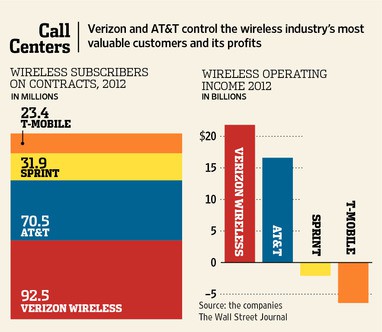

We see the same warped thinking in the broadband marketplace, particularly with usage caps, consumption billing, junk fees and the general ever-increasing price of broadband itself.

On providers’ quarterly results conference calls, the regular questions challenging leaders of the industry are not about providers charging too much for too little. The real concern is that your ISP is leaving too much ripe fruit on the tree:

- Where is the revenue-boosting usage caps and consumption billing, Time Warner Cable?

- Comcast: can’t you raise prices further on those recent speed increases to maximize additional revenue?

- Verizon: why are you spending so much on fiber broadband upgrades customers love when that money could have gone back to shareholders?

- AT&T: Is there anything else you can do to exploit your market share and make even more money from costly data plans?

The best ways a consumer can reward a good broadband provider include remaining a loyal customer, paying your bill on time and upgrading to faster speeds as needed. For Wall Street, the growing demand for broadband is a sign there is plenty of wiggle room for at-will rate increases, new fees and surcharges, contract tricks and traps, customer service cuts, and monetizing usage wherever possible. After all, you probably won’t cancel because the other guy in town is doing the same thing.

This is what sets the broadband marketplace of today apart from most retailers: consumers don’t have 10-20 other choices to take their business to if they are fed up.

Comcast or AT&T? Both charge a lot and have usage limits on their broadband service for no good reason. Your other alternatives? A wireless provider charging even more with an even lower usage cap. Or you can always go without.

While providers may tell you there is a healthy, competitive broadband marketplace, Wall Street knows better. When Time Warner Cable recently announced it would dramatically curtail new customer promotions and concentrate on delivering fewer services for more money, nobody bothered asking whether this would result in a stampede to the competition. What competition?

Although Google is delivering much-needed, game-changing competition in a tiny handful of cities, most Americans will not benefit because the best upgrades and lowest prices are only available where Google threatens the status quo. A larger number of municipalities are done putting their broadband (and economic) future in the hands of the phone and cable company and are building their own digital infrastructure for the good of their communities.

For everyone else, we can dream that one day, someday, the cable and phone company most Americans do business with will be forced to run their own JCPenney-like apology tour for years of abusive pricing and mediocre “good enough for you” broadband with unwarranted usage limits. Time Warner Cable went half way, but until competition or oversight forces some dramatic changes, we should not count on providers to actually listen to what customers want. They don’t believe they need to listen to earn or keep your business.

Subscribe

Subscribe

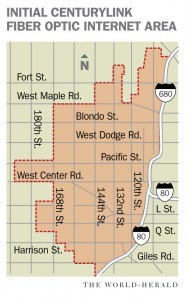

CenturyLink now sells up to 40Mbps speeds in Omaha, with a 300GB monthly usage cap. The company has not said if it intends to apply a usage limit on its fiber customers.

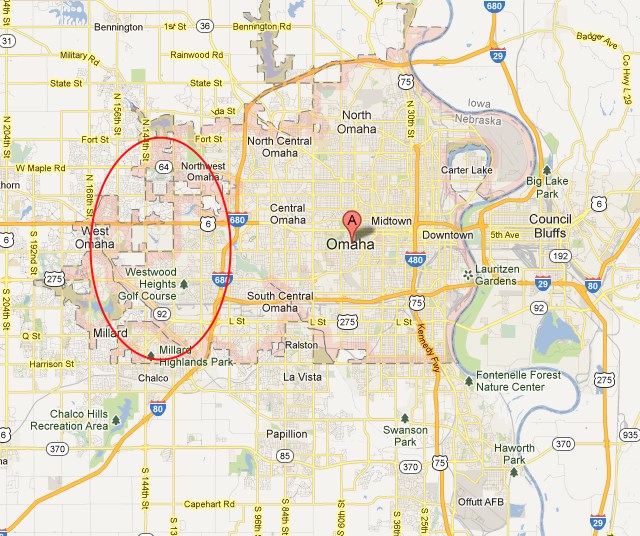

CenturyLink now sells up to 40Mbps speeds in Omaha, with a 300GB monthly usage cap. The company has not said if it intends to apply a usage limit on its fiber customers. Only around 12% of metropolitan Omaha will have access to the experimental fiber service, primarily those living in West Omaha. The network will bypass residents that live further east. The boundaries of the forthcoming fiber network are notable: West Omaha comprises mostly affluent middle and upper class professionals and is one of the wealthiest areas in the metropolitan region. Winning a right to offer service on a limited basis within Omaha is an important consideration for telecom companies like CenturyLink.

Only around 12% of metropolitan Omaha will have access to the experimental fiber service, primarily those living in West Omaha. The network will bypass residents that live further east. The boundaries of the forthcoming fiber network are notable: West Omaha comprises mostly affluent middle and upper class professionals and is one of the wealthiest areas in the metropolitan region. Winning a right to offer service on a limited basis within Omaha is an important consideration for telecom companies like CenturyLink.

I’ve known Tom Wheeler for many years, and he is an inspired pick to lead the FCC. Mr. Wheeler’s combination of high intelligence, broad experience, and in-depth knowledge of the industry may, in fact, make him one of the most qualified people ever named to run the agency.

I’ve known Tom Wheeler for many years, and he is an inspired pick to lead the FCC. Mr. Wheeler’s combination of high intelligence, broad experience, and in-depth knowledge of the industry may, in fact, make him one of the most qualified people ever named to run the agency.

We congratulate Tom Wheeler on his nomination as Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. His vast knowledge of the communications industry, as well as his proven leadership, will be invaluable as the Commission sets its course for our nation’s digital future. We applaud President Obama’s nomination and we look forward to working with the Commission under Tom’s leadership.

We congratulate Tom Wheeler on his nomination as Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. His vast knowledge of the communications industry, as well as his proven leadership, will be invaluable as the Commission sets its course for our nation’s digital future. We applaud President Obama’s nomination and we look forward to working with the Commission under Tom’s leadership. Telecommunications Industry Association

Telecommunications Industry Association

AT&T is seeking freedom from regulation, oversight and the right to abandon its landline network with the assistance of Connecticut legislators who modeled a state deregulation measure on recommendations from the corporate-funded, AT&T-backed, American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

AT&T is seeking freedom from regulation, oversight and the right to abandon its landline network with the assistance of Connecticut legislators who modeled a state deregulation measure on recommendations from the corporate-funded, AT&T-backed, American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

The Justice Department echoes critics’ contentions that given a chance, large wireless carriers will “warehouse” acquired spectrum, unused, denying it from the competition. Carriers object to that claim, calling it baseless. But incentives remain for providers to drag their feet: spectrum warehousing forces competitors to pay even higher prices for other scarce spectrum, the necessity of constructing a larger network of costly cell towers to offer robust coverage, and fighting customers’ perceptions of inferior quality indoor phone reception.

The Justice Department echoes critics’ contentions that given a chance, large wireless carriers will “warehouse” acquired spectrum, unused, denying it from the competition. Carriers object to that claim, calling it baseless. But incentives remain for providers to drag their feet: spectrum warehousing forces competitors to pay even higher prices for other scarce spectrum, the necessity of constructing a larger network of costly cell towers to offer robust coverage, and fighting customers’ perceptions of inferior quality indoor phone reception.