The United States may be a leader in many things, but broadband isn’t one of them. The country has now fallen two more positions — to 19th place, behind South Korea, Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom, and even Iceland, since the Berkman Center for Internet and Society released its last rankings in 2009.

In 2004, President George W. Bush complained about the U.S. falling to 10th place, which he declared was “ten spots too low.”

Now eastern Europe and former Soviet Republics in the Baltics threaten to overtake the United States, and countries in southeast Asia already have. Innovation in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand means deploying fiber to the home service to the vast majority of the population. Innovation in North America means conjuring up new pricing schemes to raise prices on broadband service and engage in competition-busting mergers and acquisitions.

But a USA Today editorial this week also places much of the blame on corporate influence inside Washington, which has promulgated legislative policies that favor telecommunications companies and throw customers under the bus.

“The simple answer is that other countries have policies that promote competition and innovation,” the editors write. “In contrast, policies here have allowed a few dominant players that control the least interesting parts of the broadband landscape (the cables and the wireless spectrum) to dominate.”

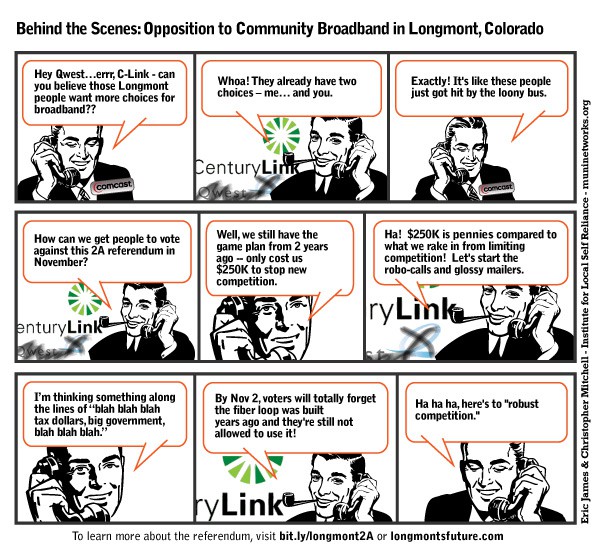

Indeed, a series of telecommunications laws enacted by Congress, combined with short-sighted policies at the Federal Communications Commission, have allowed a handful of super-sized players to own and control broadband service in America, resulting in providers establishing non-competing fiefdoms that avoid head-on competition.

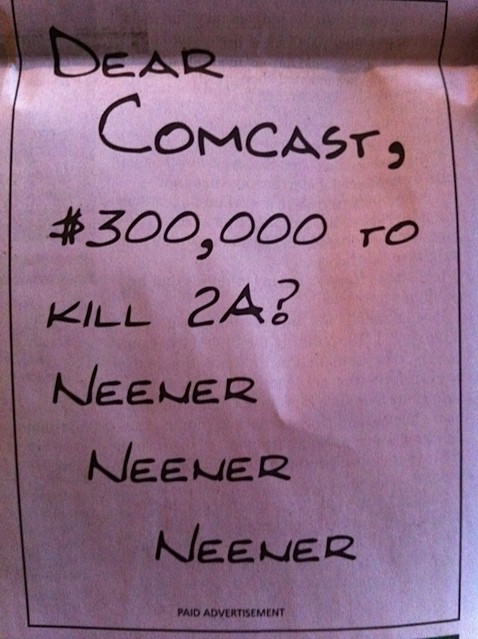

The worst policy of all allowed broadband providers to keep competitors from reaching customers over existing broadband networks. During the days of dial-up, you could purchase Internet access from the phone company, a large provider like MSN or AOL, or thousands of smaller regional and local service providers. Simply dial a local access number and you were connected to the provider of your choice. Now, U.S. law gives broadband network operators the right to restrict these independents from selling service over their networks. Comcast need not sell anything other than Comcast Internet. Frontier Communications can make a killing selling its own DSL service, while protecting that revenue from other Internet Service Providers who might sell the service over Frontier’s network for half the price. Time Warner Cable voluntarily allows Earthlink and a handful of other companies to sell cable broadband service over its infrastructure, but at prices equal to or higher than what Time Warner charges itself.

Broadband providers argue that allowing competitors to sell service on their network would discourage future investment and rob shareholders a return on investments already made. Today, major cable operators and phone companies are falling all over themselves denying they are in anything but the broadband business. It has become an enormously lucrative enterprise, more profitable than television or telephone service.

USA Today compares the broadband landscape back home with that in South Korea — perennially the world’s fastest, and considerably less expensive than what North Americans pay for service:

South Korea has made broadband a national priority, mandating deployment and in some cases giving private companies incentives to build out. It has also prevented major players from monopolizing their businesses, encouraging competition and innovation. In South Korea, consumers can get broadband service from a cable or telecom company. But they may also choose among myriad independent providers that are given access to the physical infrastructure. This competition keeps prices down and the quality of service high.

[…] But over time, cable and telecom companies worked the courts and Congress to make sure that this competitive world would never come to be [in the United States]. […] Wireless is a bit better. But the market has remained a near duopoly, with none of the smaller players emerging as a strong competitor to AT&T and Verizon.

The same open network concept has fought its way forward in Canada (where Bell has worked furiously to sabotage the business plans of independent providers) and in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand where all three governments have decided the best solution would be to scrap the ancient landline network and start fresh with an open-to-all-comers fiber to the home service.

Back home in the States it is business as usual with increasing broadband prices and the looming prospect of usage-limiting schemes designed to cut capital costs, monetize broadband usage, and stop cord-cutting.

The opposing point of view comes courtesy of dollar-a-holler, corporate-backed think tank The Heartland Institute, who is stuck quoting notorious industry-funded studies and think tanks like the Discovery Institute and the Technology Policy Institute:

The idea that European and Asian countries are lapping America in the race for broadband speed and penetration is a fallacy created with statistics comparing “persons” instead of “households.” Once you make that correction, the USA is firmly planted among the top of industrialized nations, as economist Scott Wallsten pointed out when he was a staffer at the Federal Communications Commission in 2009.

And as tech researcher Bret Swanson of Entropy Economics points out, if you measure Internet usage by gigabytes used per month — a better measure of the speed and utility of networks — the USA has nearly lapped Western Europe once and Asia twice.

If you measure how many mouse clicks customers in New York make on a Thursday afternoon, we could be number one as well! Gigabytes used per month does not measure the speed or price of service on broadband networks, considerations that actually do impact broadband rankings.

Mr. Wallsten is a familiar favorite go-to-guy for The Heartland Institute. He’s also the choice of Time Warner Cable, who paid him $20,000 for a 2010 essay: “The Future of Digital Communications Research and Policy.”

There is big money to be made writing corporate-funded research reports. Bret Swanson knows that very well, having been involved with the Discovery Institute, a “research group” that delivers paid, “credentialed” reports to telecommunications company clients who waive them before Congress to support their positions. Swanson is also a “Visiting Fellow” at Arts+Labs/Digital Society, which counted as its “partners” AT&T and Verizon.

The gentleman from Heartland also quotes from the misnamed “Progressive Policy Institute,” which counts among its funding partners, AT&T.

It would have been probably easier (but ineffectively transparent) to simply quote from AT&T and Comcast directly.

The Heartland Institute, unsurprisingly, believes letting existing broadband providers deliver service exactly the way they want is the best option:

The digital economy — one of the only vibrant economic sectors left — doesn’t need more government “investment” or regulation. It needs only for government to butt out and let the market work the magic that continues to bring us the marvels of the modern age.

That magic will cost you $50 a month and rising. If some providers have their way, while the rest of the world abandons usage caps, American providers can’t wait to slap them on, reducing the value of your service even further.

Subscribe

Subscribe