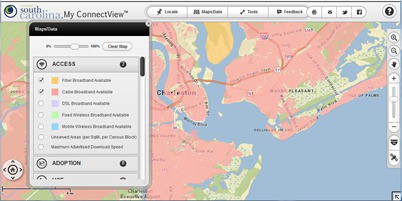

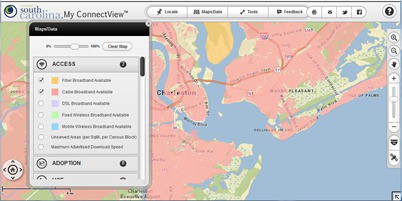

Joe Roget has one word for South Carolina’s Broadband Availability Map: “nuts.”

Joe Roget has one word for South Carolina’s Broadband Availability Map: “nuts.”

The 72 year old resident of a small town in South Carolina was excited to read a new statewide broadband availability map showed his street was currently getting DSL service from one of South Carolina’s largest phone companies. But that was news to AT&T, who provides landline phone service.

“They said they had no idea what I was talking about and that whatever map data I was looking at was totally wrong,” Roget reports to Stop the Cap! “The operator was frank with me, saying it was highly unlikely I would ever receive DSL from AT&T and the company was really not expanding DSL access any longer.”

Karen, a Stop the Cap! reader near Denmark, S.C., reported a similar story.

Karen, a Stop the Cap! reader near Denmark, S.C., reported a similar story.

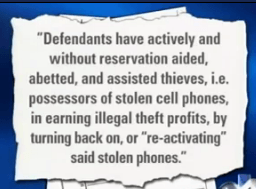

“The broadband map Connect South Carolina has gotten a government grant to produce is total fiction in my area and is little more than cable and phone company wishful thinking,” Karen reports.

Karen says not only does her street show DSL as readily available, but cable broadband as well. Karen and her neighbors can get neither.

“‘Never have, never will’ seems to be the attitude unless we pay $20,000 to the cable company to extend wiring down the street,” Karen says. “The phone company doesn’t have time to even consider that, but their call center is nowhere near South Carolina so those people don’t care.”

Roget wonders exactly how Connect South Carolina, a chapter of the industry-connected Connected Nation group, got their data.

The answer: it largely collects it from the data providers volunteer themselves.

“Did anyone ever bother to use some of the millions of taxpayer dollars this group got to actually verify what the cable and phone companies handed out to make sure it was real?” Roget asks.

Darryl Coffey, an engineering consultant for the group, says he spends countless hours trying to verify the data providers submit to the group.

In South Carolina, I verify each of these platforms by going out into the field with tools, test equipment and data. We refer to this process as “provider validation.”

Provider validation involves driving hundreds of miles following telephone and cable lines, or testing wireless signals in neighborhoods as well as in remote areas.

“I have basic phone service at my home, and I don’t know how Mr. Coffey can follow a phone line to determine if it also can provide me with DSL,” Roget says. “I could tell him, or anyone else at Connected South Carolina, it most certainly does not — had they asked.”

“I have basic phone service at my home, and I don’t know how Mr. Coffey can follow a phone line to determine if it also can provide me with DSL,” Roget says. “I could tell him, or anyone else at Connected South Carolina, it most certainly does not — had they asked.”

Roget is also upset that South Carolina’s legislature is interested in preventing local communities from deploying their own broadband networks to fill in the gaps where large telecommunications companies refuse to provide service. Only he wonders exactly how legislators will know there is a broadband gap if the group drawing the maps, based on what providers tell them, shows there isn’t a problem.

“What a scam,” Roget concludes. “An industry-backed group draws maps of data volunteered by the providers themselves that legislators use to prove there is no broadband problem in South Carolina and no need for towns and cities to build their own service.”

Karen has virtually given up on South Carolina officials representing the interests of South Carolina’s citizens.

“They look out for the companies, not the people,” Karen says. “It seems if we want better broadband, we will have to move somewhere else, preferably someplace that isn’t dumb or corrupt enough to let the broadband industry control our broadband future.”

AT&T will increase the capacity of Tampa Bay’s cell phone network to handle 4-5 times the traffic it used to, to serve the needs of the upcoming three-day Republican National Convention to be held in the city in late August.

AT&T will increase the capacity of Tampa Bay’s cell phone network to handle 4-5 times the traffic it used to, to serve the needs of the upcoming three-day Republican National Convention to be held in the city in late August.

Subscribe

Subscribe