![]() A handful of large sized Internet Service Providers threaten to strangle Canada’s transition to a digital-ready economy.

A handful of large sized Internet Service Providers threaten to strangle Canada’s transition to a digital-ready economy.

The Globe & Mail, Canada’s largest national newspaper, this week called out the country’s broadband conditions. The country is falling behind, says the editorial, and without fast action to change things, “the innovations that could employ our future work force could well pass us by.”

One passage should puncture Canada’s complacency: “Canada … is often thought of as a very high performer, based on the most commonly used benchmark of penetration per 100 inhabitants. Because our analysis includes important measures on which Canada has had weaker outcomes – prices, speeds and 3G mobile broadband penetration … it shows up as quite a weak performer, overall.”

The newspaper was particularly critical of current providers, and the regulatory body that oversees them — the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). Recent CRTC policies and rulings have allowed a handful of providers to place a strangehold on the Canadian broadband marketplace, reducing competition and controlling wholesale pricing and access policies. Bell, Canada’s largest telecommunication company, was awarded approval of a policy to implement usage-based billing on the company’s wholesale accounts. Many independent service providers obtain broadband access from wholesale accounts with Bell. When they themselves face usage-billing, so shall customers, who now have fewer reasons to choose an alternative provider in the first place.

There is no magic recipe, but some prescriptions are worth heeding as Canada develops its Internet strategy. The report recommends open access policies, in which companies that build infrastructure for mobile and fixed broadband access are encouraged or required to lease that infrastructure to the competition.

But in Canada, limits on foreign ownership and inconsistent CRTC decisions have lowered the amount of competition needed to spur new and better offerings. There was less stimulus spending on projects to support more widespread Internet access in Canada than there was elsewhere. Decisions on related policy issues, such as copyright reform, have been delayed. A national conference on the digital economy generated buzz – ministers Tony Clement and James Moore are reputed to “get it” – but yielded few results. Our best hope to lead on Internet innovation, the Long-Term Evolution platform being developed by Nortel as a successor to 3G, is now largely in foreign hands.

The editorial provoked a response from Jay Innes, vice-president-public affairs, at Rogers Communications, one of Canada’s largest cable and wireless operators. He sought to change the subject:

For Canada to win in a global digital economy, our country needs to establish a national vision that looks beyond the often-flawed statistical rankings of broadband infrastructure. What we need to understand is why so many Canadian households still don’t have computers, why Canada is lagging in scientific research, and how we should best promote the development of Canadian content and applications.

Internet providers called out for offering slow service at high prices routinely attack surveys that measure broadband speed as beside the point, and then just as quickly blame something else for their problems.

Innes fails to recognize that Canadian broadband service, speed, and access policies are directly on point when answering his question about the dearth of Canadian content and applications. The fact is, with near-universal Internet Overcharging schemes like usage caps and usage-based billing, no innovative high bandwidth developer is going to plunge headfirst into the Canadian market. When that developer realizes Canadian ISPs also have the right to artificially impede their content using “network management” speed-throttling techniques, they won’t even dip a toe in the water.

Canadian media websites, for example, contain dramatically less multimedia content for visitors to explore than their American counterparts. Multimedia eats into your monthly usage allowance, so Canadians think twice before watching. Hulu and other online video enterprises don’t bother to license content for Canada because usage limits and overlimit amounts discourage viewing. Canadians who don’t want even higher telecommunications bills may simply decide the Internet is not for them, and they can get by without a computer.

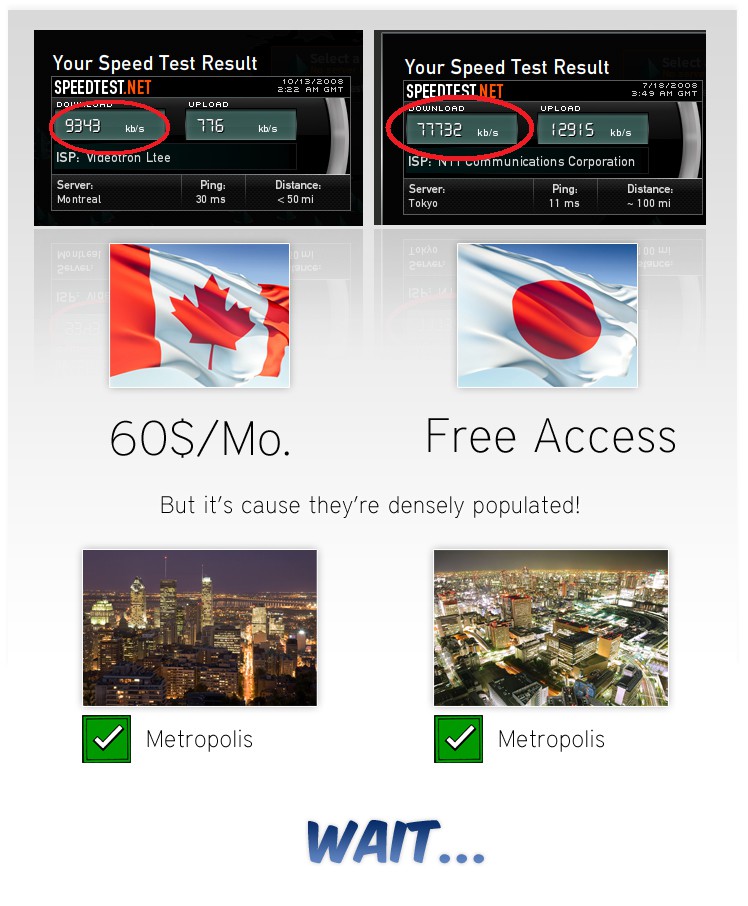

If Innes wants to get in touch with his fellow Canadians, who are already well aware of his industry’s pricing and usage schemes, he can read Canadian bloggers like Éric St-Jean, who calls out Vidéotron and Bell:

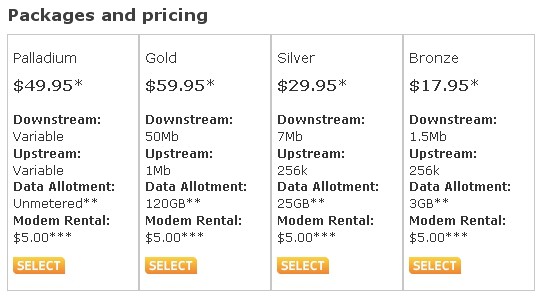

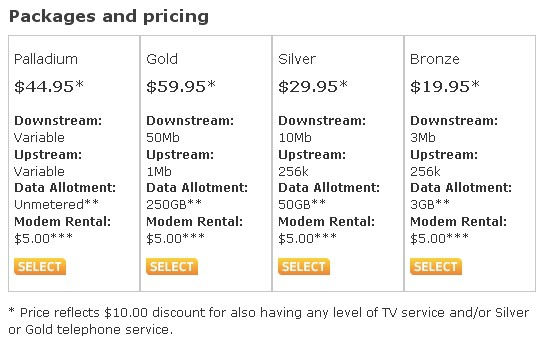

It’s funny how we hear about Vidéotron‘s Ultimate Speed 50 Mbps access, and now Bell‘s Fibe 25 Mbps access and we’re told how great they are. They’re actually both humongous ripoffs, if you have even basic math skills and five minutes ahead of you. Why? They both advertise great speeds, but hidden behind those figures, in very small print, behind two or three clicks from the product pages, you’ll find abysmal monthly transfer caps. This means that, yes you have a very fast connection. But if you were to use it fully, you’d very quickly fall into a lot of debt.

Vidéotron’s transfer cap for their 50 Mbps service is at 100GB/month combined up/down – this means you will bust your cap within 5 *hours* if you were to fill your pipe. In turn, this means that you simply CANNOT reasonably use this service. If you were to use your service fully – at 50Mbps – for the whole month, you would get a bill for $24,132.50. Granted, that’s a lot of data. But I just want to point out how ridiculous the terms of that offer are – it should not be legal.

Bell’s 25Mbps service has – get this – a 20GB transfer cap on it. They offer an extra 40GB for 5$/month. The base rate is $64.95/month (after 12 months). The overage is charged at the whopping rate of $2.50/GB. So, if we take the base service + the extra 40GB, we’ll get to that limit within about 5.3 hours.

All I have is a 5Mbps (DSL) connection from Teksavvy. But for $43.95 I have no transfer cap at all, a fixed IP, and immediate access to support techs who’ll know what I’m talking about. But they can’t offer more than 5Mbps.

I honestly don’t understand how the media isn’t picking up on Bell and Vidéotron’s tactics, and how this can be legal. To me it’s completely false advertising: they advertise great speeds (barely on par with the international market, though), which you can’t reasonably use. All this needs is a lawsuit.

When will we get decent Internet access in Canada?

That’s a question Innes is not prepared to answer because, for him and his provider friends, “decent” access is already here.

Innovation requires freedom to innovate. Rationed broadband service guarantees “stick to the basics” thinking. But as long as providers can live comfortably off the proceeds, why should they change the winning formula that provides them with financial success?

Subscribe

Subscribe