The Internet Innovation Alliance this week unveiled its 2013 Broadband Guide to the 113th Congress, outlining recommendations for a better broadband future that just so happen to fall in step with AT&T’s lobbying action agenda, guaranteeing near-total telecom deregulation and abandoning rural America’s wired telecommunications networks.

The Internet Innovation Alliance this week unveiled its 2013 Broadband Guide to the 113th Congress, outlining recommendations for a better broadband future that just so happen to fall in step with AT&T’s lobbying action agenda, guaranteeing near-total telecom deregulation and abandoning rural America’s wired telecommunications networks.

That should come as no surprise, because the IIA’s principal backer is AT&T, along with a host of public interest and non-profit groups that have received significant contributions and backing from the phone giant.

The IIA’s chief recommendation: allow phone companies to abandon wired landline networks in favor of all-IP-based technologies that escape most regulatory requirements and are not subject to much oversight by local, state, or federal officials.

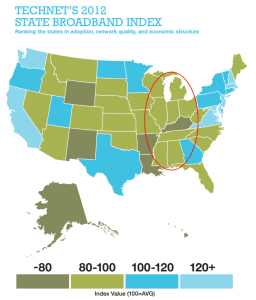

The IIA guide unintentionally illustrates that AT&T’s largest service area in the central and southern U.S. has some of the lowest broadband rankings in the country.

In order for consumers to enjoy the speed and bandwidth capacity of IP networks and to take advantage of the programs and services (including education, gaming, entertainment, social media) that require fast and robust data transmission, the United States should encourage the upgrade to a digital, all-Internet Protocol (IP) broadband infrastructure. Current legacy wired networks fail to meet the FCC’s definition of broadband, yet outdated laws essentially assume that incumbent telephone companies continue to maintain and operate these slow, antiquated networks, even as incumbents invest and deploy separate IP infrastructure and fewer and fewer consumers rely on the outdated voice-only networks.

Requiring incumbent telephone providers to maintain costly antiquated networks siphons investment away from deployment of advanced, high-speed next-generation IP-based networks that consumers prefer. Reforming antiquated 1930s regulations designed for monopoly providers in a copper-wire, analog era will encourage the private sector investment needed to upgrade non-IP-based facilities with newer and faster broadband infrastructure, creating jobs and growing our economy.

In addition, today’s 4G LTE wireless networks are IP-based, but the spectrum required to fuel consumers’ advanced wireless devices on these networks is becoming severely congested. Releasing more spectrum, the radio waves that carry everything from television to texts to mobile video, is necessary to maintain and improve service quality on wireless networks. The government controls the allocation of spectrum and should reallocate more of it for consumer use in order to sustain the increasing public demand for data and continue the benefits offered by the mobile revolution.

Nowhere in IIA’s guide does the “Alliance” disclose its largest backer is AT&T, one of the “telephone providers” IIA talks about as if it was a third party that had no direct connection to the group.

IIA’s guide takes care not to come down too hard on its benefactor for not upgrading rural telecommunications networks to support next generation broadband. In fact, AT&T has dragged its feet providing even ordinary DSL service in many of its rural service areas. The IIA is also careful not to disclose AT&T’s real plan: not to upgrade existing networks to fiber but rather abandon them altogether in favor of its high-profit, high revenue wireless service. That assures everyone deemed unworthy of wired broadband investment will be relegated to the company’s high-cost wireless platform with paltry usage caps and speed throttles.

At the start of 2013, we are witnessing exciting changes enabled by mobile broadband: an app economy that didn’t even exist five years ago now employs more than 500,000 Americans, according to Economist Michael Mandel; the inexorable shift to the cloud and its more efficient information storage; proliferating creative tools that are transforming consumers’ business and personal lives; rapacious appetite for faster speeds, greater bandwidth opportunity and more capacious storage; overwhelming competition with 90 percent of consumers able to choose from at least five different providers, as reported by the FCC; and accelerating innovation cycles where tomorrow’s technology is invented today. The future of broadband is bright and the benefits to consumers and our nation could be boundless. To realize these benefits we need only to let our innovators innovate, our entrepreneurs compete, and ensure our consumers have the knowledge and freedom to make the most of the technology available to them.

…and let AT&T do whatever and charge whatever it wants, while depriving rural America of a wired broadband future.

The IIA hopes its message gets through to members of Congress. Helping make that happen are two former Washington, D.C. insiders that have bipartisan support for AT&T’s agenda.

“We love technology here and believe in its power to change the country, the world, and that it’s a non-partisan issue,” gushes Bruce Mehlman, IIA’s founding co-chairman and former assistant secretary of commerce for technology policy in the George W. Bush Administration.

Mehlman was recognized by Washingtonian Magazine as one of the city’s top lobbyists and is a founding partner of his own lobbying firm. Mehlman is considered an expert in running issue campaigns and “developing advanced lobbying strategies that achieve impactful policy outcomes.” At least AT&T hopes so.

Mehlman’s D.C. lobbying firm promises “we get things done in Washington.”

“It’s critical that policymakers be well-informed as they make decisions affecting the Internet in order to promote and encourage the expansion of Internet investment, access and adoption,” echoed IIA honorary chairman Rick Boucher, a former Democratic member of Congress from the state of Virginia.

Boucher has never strayed too far from AT&T money either. AT&T was his third largest contributor overall from 1989 until he lost re-election in 2010. Today, Boucher is a partner in the law firm of Sidley Austin, which has represented AT&T’s interests for over 100 years.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Susan Crawford’s new book, “Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age,” is on the receiving end of a lot of heat from industry lobbyists and those working for shadowy think tanks and “consumer groups.”

Susan Crawford’s new book, “Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age,” is on the receiving end of a lot of heat from industry lobbyists and those working for shadowy think tanks and “consumer groups.”

Wildman does not mention his cable benefactors earn a higher percentage of profit on broadband than oil sheikhs in the Middle East rake in charging $90+ for a barrel of oil. So it is unsurprising his analysis lacks one simple solution providers could use to differentiate their services and enhance broadband penetration: lower the price to compete. He also ignores the fact that true usage pricing would offer consumers a chance to pay only for what they actually consumed during a month, but those plans are not on offer anywhere.

Wildman does not mention his cable benefactors earn a higher percentage of profit on broadband than oil sheikhs in the Middle East rake in charging $90+ for a barrel of oil. So it is unsurprising his analysis lacks one simple solution providers could use to differentiate their services and enhance broadband penetration: lower the price to compete. He also ignores the fact that true usage pricing would offer consumers a chance to pay only for what they actually consumed during a month, but those plans are not on offer anywhere.