Del. Kathy Byron (R-Big Telecom)

What is one of the most effective ways to stop competition in its tracks before it can even get off the ground? Reward a state legislator with generous campaign contributions who introduces a bill banning your would-be competitor and get back to business as usual.

Delegate Kathy Byron (R-Campbell County) has broadband, but many of the people who live and work in central and western Virginia near her district don’t. Located in south-central Virginia, the county of 55,000 endures similar broadband availability and quality problems other communities in the western half of the state experience. Located near the Blue Ridge Mountains, the county seat of Rustburg has areas served by DSL, and many other areas that are not. For telecom companies serving mountainous and rural communities in this part of the state, broadband is often not economically viable enough to meet Return On Investment formulas. In fact, the problems are so significant, the southwestern Virginia community of Claudville was selected as the nation’s first testing ground for “white space” wireless broadband, designed to serve sparsely populated rural areas.

Byron’s district in Campbell County is neither wealthy or rich in internet options. Like other communities in the region, the decline of manufacturing and the transition away from tobacco production has created enormous economic challenges. Campbell County is continuing to rely heavily on agriculture while other communities in Virginia and the Carolinas are reinventing themselves to participate in the 21st century knowledge economy. That requires 21st century broadband service, which Campbell County lacks.

Last fall, Campbell County Public Schools assistant superintendent Robert Arnold provided a frank assessment of the area’s broadband problems, telling The News & Advance schoolchildren in his district suffer from a “homework gap,” unable to complete assignments requiring the internet at home because those homes lacked access. A recent trial of “white space” broadband in the area proved unsatisfactory because, in Arnold’s view, it was unreliable.

“We’re not seeing it as a reliable solution to our problems to get internet more readily available to kids that don’t have it in the different parts of our county where there are a lot of dead spots,” Arnold said.

Even wireless providers have not stepped up. Efforts to encourage cellular companies to place antennas on the same towers used for the “white space” broadband experiment have failed as well. The newspaper reports the lack of population makes private providers “squeamish about expanding there.”

Even wireless providers have not stepped up. Efforts to encourage cellular companies to place antennas on the same towers used for the “white space” broadband experiment have failed as well. The newspaper reports the lack of population makes private providers “squeamish about expanding there.”

The Campbell County school system managed to switch to a fiber optic network, but the only chance students will have that option at home is if local communities choose to offer it themselves and that will never happen if Ms. Byron’s bill becomes law.

Despite the broadband challenges in her district and the failure of private providers to correct them, Byron went ahead this month and introduced the ironically-named “Virginia Broadband Deployment Act,” another bought-and-paid-for industry-ghostwritten municipal broadband ban bill that would grant near-monopoly control to the same providers that have steadfastly refused to improve rural broadband in Virginia.

Her bill, according to The Roanoke Times, is the height of hypocrisy for a Republican claiming to be pro-business development:

Byron’s bill would make it difficult for existing municipal broadband authorities to expand and new ones to get started. Curiously, for a bill sponsored by a Republican, it would create more regulation, by requiring that the state authorize any creation or expansion of a broadband authority (plus lays on other regulations, as well.) For a bill that purports to protect the free market, it actually distrusts the free market: If telecommunications companies were already providing the service the rest of the business community wanted, the business community wouldn’t be clamoring for local governments to step in.

Spent lavishly on Byron – her second largest contributor.

The newspaper shouldn’t be surprised. Politicians willing to introduce these lovingly hand-crafted turf protection bills ask themselves only one question: are the generous corporate campaign contributions that usually accompany these “model bills” still worth it if the voters find out? Even if they do, a well-funded propaganda campaign sponsored by Big Telecom companies slamming municipal broadband as a government internet takeover or a guaranteed economic failure can help give politicians enough cover to avoid being exposed for selling constituents down the river.

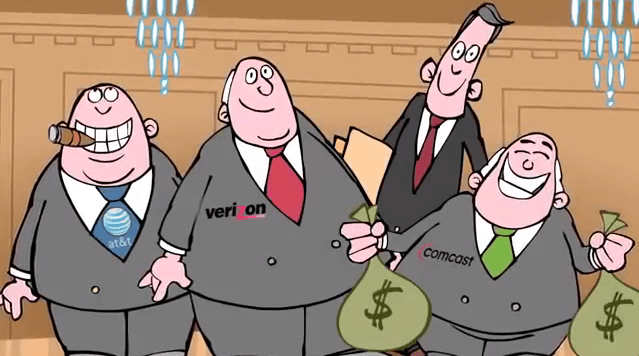

It will therefore come as no surprise to regular Stop the Cap! readers that Virginia’s largest telecom companies have spent lavishly on Ms. Byron over the years. Her second largest contributor (next to the Republican Party of Virginia) is Verizon, which spent considerably more on her campaign than other well-heeled companies including Anthem and the Virginia banking lobby. Another major contributor is the Virginia Cable Telecommunications Association (more on that organization later). Others bringing checks include: AT&T, Sprint, CenturyLink, Comcast and the Virginia Telecommunications Association.

The pattern is all too familiar. Politicians take a sudden interest in telecommunications public policy and almost by magic produce a very detailed (and suspiciously similar) piece of legislation designed to make life impossible for public and community broadband projects, while claiming their bill will improve broadband.

In many cases, the politicians introducing these broadband ban bills are surprisingly unprepared to answer detailed questions about their own legislation, counting on local media to not scrutinize their logic too closely. But every so often, the blank stares and subject-changing that occurs when challenges are put to the alleged authors make us question if they actually read their own bill.

We have.

Byron is on ALEC’s Communications and Technology Task Force

Also of concern, Ms. Byron and her bill expose several conflicts of interest she has elected to ignore and hope nobody notices, like her membership on the American Legislative Exchange Council’s Communications and Technology Task Force, notorious for promulgating state bills restricting or banning public broadband. ALEC funding comes, in part, from some of the nation’s largest telecom companies.

We noticed.

The backlash Ms. Byron is now receiving from unhappy rural Virginia communities and local media that have read her bill has apparently surprised her, and in subsequent newspaper letters to the editor, she has taken to playing the victim card. But that has not stopped her from maligning municipal broadband projects, hoping that shaking those shiny keys will distract enough people from focusing on what is actually in her bill.

We put her keys away.

Stop the Cap! has reviewed her bill, also known as House Bill 2108, and what we found astonished us more than usual, and we’ve seen just about every kind of shilling imaginable:

§ 56-484.28. Provision of broadband expansion services.

Notwithstanding any provision of the Virginia Wireless Service Authorities Act (§ 15.2-5431.1 et seq.) or any other provision of law, a locality or any affiliate may own and operate a broadband or Internet communications system, including ownership or lease of fiber optic or other communications lines and facilities, to provide broadband expansion services only if the following conditions are met:

1. The locality or its affiliate has obtained a comprehensive broadband assessment by report or study, by the Center for Innovative Technology, or an independent consulting firm knowledgeable and experienced in analyzing broadband deployment, which report or study is made available to the public and specifically identifies any unserved areas. The locality or its affiliate shall be responsible for all fees charged by the Center for Innovative Technology or an independent consulting firm for the preparation of such comprehensive broadband assessment report or study.

2. Based upon the comprehensive broadband assessment, the locality or its affiliate formally adopts and publishes specific broadband goals regarding capacity, geography and documented demand for Internet services in the specific unserved areas which the locality or its affiliate desires to address.

3. The locality or its affiliate has issued a request or solicitation for proposals, consistent with the specific broadband goals of the locality previously identified, requesting the capital cost which an existing for-profit local Internet service provider offering communications services with broadband speeds would incur to meet the locality’s specific broadband goals by extending or upgrading such services with broadband speeds to any specific unserved areas of the locality identified in the comprehensive broadband assessment. Copies of such request or solicitation shall be sent to any franchised cable operator and other known Internet service providers with local facilities offering communications services in the locality at least 180 days in advance of the deadline for the response to the request or solicitation for proposals. The governing body of the locality or its affiliate shall analyze any responses it receives to determine if capital grants or subsidies by the locality to pay for such extension by an existing provider would be more cost effective than construction and operation of a new distribution system by the locality or its affiliate.

4. If no incumbent broadband provider advises the governing body of the locality within six months after the release of the request or solicitation for proposal that it is willing or able to meet the local goals, either without a capital grant or subsidy, or with the capital grant or subsidy or portion thereof proposed by the locality, then the governing body of the locality or its affiliate, after a public hearing, may vote to authorize one or more projects, consistent with the specific broadband goals of the locality previously identified, to provide broadband expansion services to unserved areas within the locality identified by the comprehensive broadband assessment report or study described above, which report or study shall not be more than one year old at the time of the public hearing. The chief executive officer of the locality or its affiliate shall certify that the comprehensive broadband assessment report or study identification of unserved areas is still correct based upon information presented at the hearing.

5. Any locality or affiliate project to provide broadband expansion services shall be designed and built or otherwise implemented so that at the time of authorization, the project (i) does not duplicate existing broadband facilities offering broadband speeds to customers, within 90 percent of the geographic area of the project, and (ii) does not duplicate service to customers who already are in a position to connect to an Internet service offering broadband speeds, for 90 percent of the projected residential and commercial customers who will be served by the project or otherwise are within the service area of the project.

6. Any locality or its affiliates seeking to offer or offering broadband expansion services shall, at least 120 days prior to commencement of construction of any project, file with the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council, (i) copies of its report or study from the Center for Innovative Technology, including any updates or supplements thereto, (ii) copies of the minutes of the meeting at which it voted to authorize the offering of broadband expansion services, (iii) a map or description of each project and projected area in which it plans to offer broadband expansion services, (iv) an annual certification by July 1 of each year that any expansion to or changes in its projects or system since the preceding July 1 still qualify as broadband expansion services, and (v) an annual certification that its provision of services meets or in the case of a prospective or an incomplete project shall meet, the requirements of subdivisions 1 through 6 of § 56-484.30. Any person who believes that any part of such filings is incomplete, incorrect or false and who is in the business of providing Internet services within the locality shall have standing to bring an action in the circuit court for the locality to seek to require the locality to either comply with the substantive and procedural content of the filings required by this section, or cease to provide services, and no bond shall be required for injunctive relief against the locality.

In condensed form, this section claims to help facilitate municipal broadband service in “unserved areas,” but then hamstrings local communities to an extent that makes offering such a service next to impossible. The irony of a Republican legislator advocating detailed and burdensome regulations for a publicly owned provider while concurrently supporting “hands-off” policies for her campaign contributor-provider pals should not be lost on her constituents.

The bill could have been called the “Virginia Duopoly Protection Act,” because it only really allows public broadband development in unserved areas, and only after a community pays for a “broadband assessment” that the bill also mandates be sent to its potential competitors — private cable and telephone companies. Imagine if AT&T was required to send copies of their business plans to Comcast and Charter.

The bill could have been called the “Virginia Duopoly Protection Act,” because it only really allows public broadband development in unserved areas, and only after a community pays for a “broadband assessment” that the bill also mandates be sent to its potential competitors — private cable and telephone companies. Imagine if AT&T was required to send copies of their business plans to Comcast and Charter.

Even worse, phone and cable companies are guaranteed a “heads-up” when a community provider is thinking about providing service, exactly where that service will go, and how much it will cost the community to offer it. Companies on the wrong side of the law used to hire spies to get that information from competitors. Byron’s bill makes Virginia communities pay for the postage required to mail those plans to telecom companies serving their area.

Being given access to what even cable and phone companies would consider highly confidential information isn’t enough. Ms. Byron’s bill allows them to take their time reading it. In fact, her bill gives incumbent providers up to six months to stall, sabotage, or undercut the community effort. They are given the right to underbid the community’s proposal and ironically deliver service in places they have previously refused to serve.

“While it’s good to be specific about what a community plans to do, incumbent providers don’t have to adhere to the same level of transparency,” noted Lisa Gonzalez at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “As a result, publicly owned networks are at a disadvantage under such requirements when an incumbent knows where, what, when, and how much a municipality intends to invest to bring service to its community. When incumbents build or upgrade, they are not subject to the same level of exposure. Potential private partners who may consider leasing infrastructure or working with a community in some other capacity could also be put off by drastic transparency rules.”

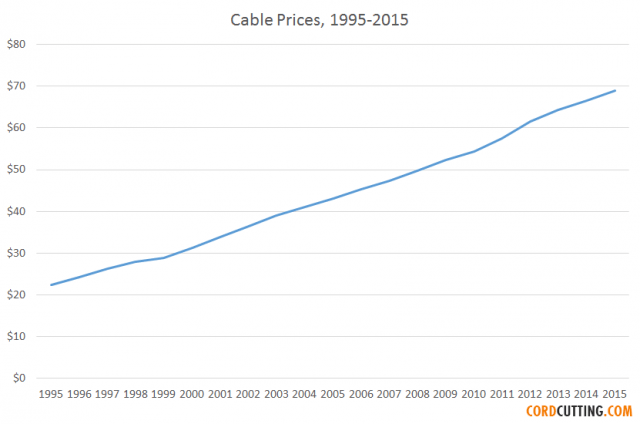

Any of Virginia’s phone and cable companies could end the demand for municipal broadband tomorrow by simply providing the level of service communities need to participate in the digital economy. That requires connected education and high quality broadband for entrepreneurs and established businesses. Instead of providing that, companies write large campaign contribution checks to state politicians like Ms. Byron to slow down or sabotage any emerging competition. While stalling germinating broadband projects, providers will spend millions to demagogue them in the local media, throw every obstacle in their path, and then point to the delays and cost overruns as evidence municipal broadband is a failure.

In Tennessee, EPB had to face down a deep-pocketed cable industry lawsuit before it could begin offering gigabit internet broadband and television service. EPB eventually won the lawsuit and the service now attracts a substantial market share in Chattanooga, but critics carp it was only successful because it got a federal grant. They ignore the fact it has paid substantial dividends in job growth and enhanced the lives of local citizens, who vote for the service with their wallets.

The fact critical cable and phone companies risk charges of hypocrisy doesn’t seem to move them, even though they are not averse to accepting tax breaks and other government goodies as well. That is why providers instead use well-funded third-party astroturf groups and legislators to do their dirty work. Byron’s bill is more obvious than most, with obstructive sections mandating very short windows for public hearings, blatant protectionism, and a thicket of bureaucratic regulations designed to give ample opportunities for industry mischief with the filing of frivolous motions to run out the clock and run up costs.

§ 56-484.29. Provision of overbuild broadband services.

Any locality or its affiliate that is providing overbuild broadband services as of July 1, 2017, may continue to serve customers within the geographic service area within which it is actually providing such services as of that date; however, except as hereafter provided such locality or its affiliate shall not subsequently expand the geographic scope of its services or expand the nature of the service being offered. Any locality or its affiliate that is not actually providing overbuild broadband services as of July 1, 2017, or if providing such services, subsequently seeks to expand the geographic territory or nature of services being offered, shall submit a proposal to the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council with a full explanation of the proposed overbuild broadband services, and if recommended by the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council, shall then require the express approval of the General Assembly through legislation approving the offering or expansion of such services by the locality or its affiliate.

Since 2008, Stop the Cap! has reviewed industry-sponsored municipal broadband ban bills, and none to date have illustrated the level of conflict of interest we see here. We call on Virginian officials to carefully investigate the ties Ms. Byron has to cable and phone companies and the ethical concerns raised from her involvement in key state bodies that can make or break rural broadband in Virginia. Byron increasingly exposes an agenda favoring incumbent phone and cable companies that just happen to contribute to her campaign — companies she seems willing to protect at any cost.

In our investigation, we uncovered several disturbing details that suggest questionable behavior from Ms. Byron, primarily from her failure to disclose materially important facts about her bill to fellow elected officials and, more importantly, the public. So far, her only defense to questions raised by the media about her bill is to play the “misunderstood victim” card:

This may be yet another example of media arrogance manifesting itself as a lack of common courtesy. But, I believe the real culprit to be something far more dangerous: the editorial’s author was not going to risk being confused by the facts.

[…] Had someone contacted me, I would have told them about my years of experience serving on Virginia’s Broadband Advisory Council, which I currently serve as chairman. The purpose of the Council is “to advise the Governor on policy and funding priorities to expedite deployment and reduce the cost of broadband access in the Commonwealth.” The Virginia Broadband Deployment Act advances that goal. That’s why legislators serving on the Council support House Bill 2108. And, we’re in good company: The Virginia Chamber of Commerce, the Virginia Association of Realtors and the Northern Virginia Technology Council have all indicated their support for House Bill 2108.

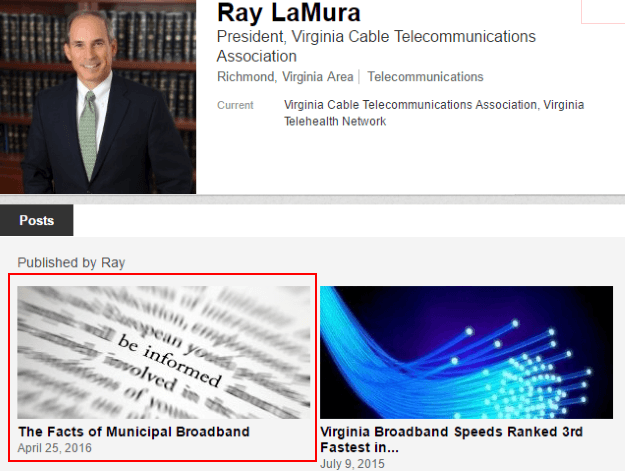

Fixed or Fair? If Byron’s bill becomes law, Ray LaMura, Virginia’s top cable lobbyist, will help decide if municipal providers can expand to compete with cable companies.

In fact, we understand Ms. Byron, her telecom industry benefactors, and the special interests she mentions as supporters only too well. We invite Ms. Byron to refute some of our facts:

While broadband in major Virginia cities is no better or worse than other large cities in the region, there are vast areas in central and western Virginia where inadequate broadband service persists, and private providers have been reluctant or unwilling to change that. As a result, some municipalities are considering offering an alternative. Ms. Byron’s bill doesn’t just deter communities from entering the broadband arena in these areas, it carpet-bombs the entrance out of existence.

The section of her bill detailing requirements for community providers seeking to expand requires them to ask permission from an entity known as the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council, which Byron disturbingly chairs. If the goal of this Council is to pave the road to improved broadband, Byron’s bill is an enormous pothole. Restricting competition won’t help the Council’s goal of winning lower prices for consumers and businesses either, and last time we checked, broadband bills in Virginia are going up, not down.

Ms. Byron’s clear conflict of interest between her bill and the Council’s goals should be grounds for her immediate resignation. It is hard to justify continuing to serve on a Council promoting better broadband while introducing bills that do the opposite. Taking political campaign contributions from the same companies that are directly responsible for the state of Virginia’s broadband today also makes it impossible for the Council to have any credibility as long as she continues to chair it.

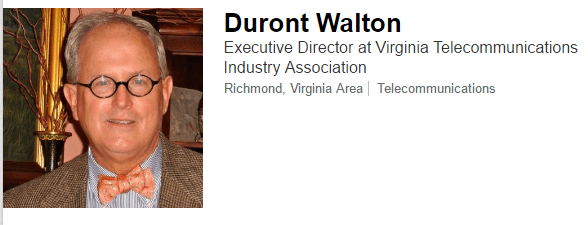

Another concern: Ms. Byron fails to disclose the Council she uses for her defense includes “citizen members” that are, in reality, some of the most important telecom industry lobbyists in the state. Ms. Byron’s bill would require communities to seek approval for broadband expansion from the same Council that counts among its members Ray LaMura, president of the Virginia Cable Telecommunications Association, the state’s largest cable industry lobbying group, and Duront Walton, executive director of the Virginia Telecommunications Industry Association, which represents the interests of several telephone companies in the state.

Conflict of Interest?: Another member of Virginia’s Broadband Advisory Council.

Does anyone believe the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council is likely to approve any broadband expansion plan that leads to direct competition with an established cable or phone company, particularly when members like Mr. LaMura write municipal broadband hit pieces prominently linked on his LinkedIn page? Does anyone expect a fair shake from Ms. Byron, who wrote (inaccurately) “the vast majority of municipal broadband systems across the country that have tried to compete with the private sector have failed.”

By all appearances, the fix is in.

While we’re discussing full disclosure, Ms. Byron also failed to mention the Virginia Chamber of Commerce is hardly a dispassionate arbiter of the merits of community broadband — it is a private business lobbying organization. The Virginia Realtors Association is also a political lobbying organization that openly endorsed Ms. Byron’s election campaign, contributed a substantial donation to it, and runs an active Political Action Committee. The Northern Virginia Technology Council is a trade and lobbying organization that counts among its members AT&T, Cox, Comcast, CenturyLink, and Verizon, to name a few. To quote NVTC’s own website: “NVTC members are business leaders focused on the broad business climate of our state and communities.”

We believe Ms. Byron when she said she was in good company. Missing from the cozy gathering are consumers looking for internet access, local governments feeling pressure from their constituents to do something about the problem, and any belief Ms. Byron’s bill will do anything except keep things as they are.

But wait, there is more:

But wait, there is more:

§ 56-484.30. Operating requirements.

The following provisions shall apply to any locality or its affiliate which offers broadband expansion services or overbuild broadband services, after July 1, 2017:

1. A locality or its affiliate shall apply, without discrimination as to itself and any affiliate, including any charges or fees for permits, access or occupancy, the locality’s ordinances, rules, and policies, including those relating to (i) obligation to serve; (ii) access to public rights of way and municipal utility poles and conduits; (iii) permitting; (iv) performance bonding; (v) reporting; and (vi) quality of service.

2. In calculating the rates charged by a locality for any communications service:

a. The locality or its affiliate shall include within its rates an amount equal to all taxes, fees, and other assessments that would be applicable to a similarly situated private provider of the same communications services, including federal, state, and local taxes; franchise fees; permit fees; pole attachment fees; and any similar fees; and

b. The locality or its affiliate shall not price any of its communications services at a level that is less than the sum of: (i) the actual direct costs of providing the service; (ii) the actual indirect costs of providing the service; and (iii) the amount determined under subdivision 2a.

3. A locality or its affiliate shall keep accurate books and records of any provision of communications services. A locality or its affiliate shall conduct an annual audit of its books and records associated with any provision of communications services, with such audit to be performed by an independent auditor approved by the Auditor of Public Accounts. Such audit shall include such criteria as the Auditor of Public Accounts deems appropriate and be filed with him, and with copies to be submitted to the Virginia Broadband Advisory Council. If, after review of such audit, the Auditor of Public Accounts determines that there are violations of this chapter, he shall provide public notice of same, and the locality or its affiliate shall take appropriate corrective action to cure past violations and prevent future violations. […]

§ 56-484.31. Sale or disposal.

Any locality or its affiliate that seeks to sell or dispose of all or any material part of the infrastructure of an internal government services, broadband expansion services, or overbuild broadband services system, or any material portion of any subscriber or service contracts in connection therewith, shall do so by a public sale or auction process after advertisement.

By now, most readers get the point. This bill is a “plan for failure” for municipal broadband.

The ideological pretzel-bending required of Ms. Byron to do the telecom industry’s bidding is a sight to behold. Byron — a Republican — is openly advocating government price regulation, demands municipal providers turn over their books to be reviewed by her Virginia Broadband Advisory Council, which includes cable and telephone company lobbyists, and requires communities that want to abandon networks that fail under this legislative gulag to sell them to the lowest bidder, likely a cable or phone company that helped write the rules.

If this anti-consumer nightmare of a bill becomes law in Virginia, Christmas for Big Telecom will come early this year, and you’re paying… again.

Subscribe

Subscribe The “Cadillac” wireless network reintroduced unlimited data, phone, and texting this week at prices that vary according to the number of lines on your account:

The “Cadillac” wireless network reintroduced unlimited data, phone, and texting this week at prices that vary according to the number of lines on your account:

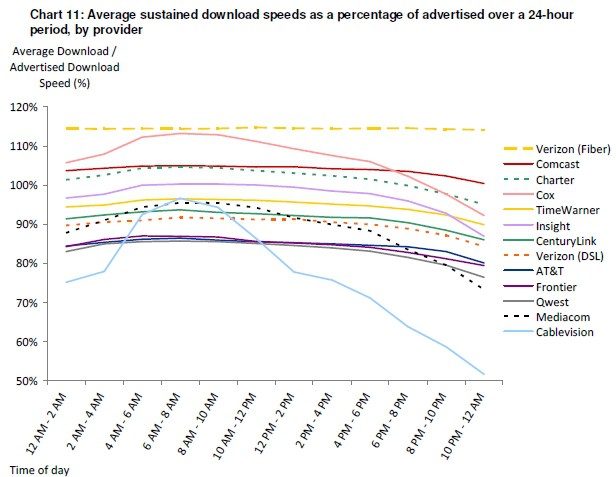

In the summer of 2014, Time Warner Cable had a problem. For three years, the Federal Communications Commission had been issuing reports about the quality of broadband service from the nation’s largest internet service providers. The raw data collected by about 800 subscribers of Time Warner Cable who volunteered to participate in the project began to worry executives because it showed their broadband service was oversold in certain large cities and was no longer capable of consistently achieving advertised speeds. Even worse, the company’s congestion problems threatened to lower Time Warner Cable’s internet performance score at the FCC.

In the summer of 2014, Time Warner Cable had a problem. For three years, the Federal Communications Commission had been issuing reports about the quality of broadband service from the nation’s largest internet service providers. The raw data collected by about 800 subscribers of Time Warner Cable who volunteered to participate in the project began to worry executives because it showed their broadband service was oversold in certain large cities and was no longer capable of consistently achieving advertised speeds. Even worse, the company’s congestion problems threatened to lower Time Warner Cable’s internet performance score at the FCC.

In 2013, a Time Warner Cable executive recognized the company’s practice of limiting company-financed expansion of their upstream connections with the rest of the internet would have serious implications for their own speed test scores, because customers were encountering nightly slowdowns on popular websites like YouTube caused by overcongested connections. Company executives feared customers participating in the Sam Knows/FCC program would soon reveal Time Warner Cable’s internet speeds were beginning to suffer some of the same peak usage problems Cablevision was encountering in 2011. The executive’s solution? Temporarily expand upstream connections just long enough to protect Time Warner Cable’s broadband speed scores:

In 2013, a Time Warner Cable executive recognized the company’s practice of limiting company-financed expansion of their upstream connections with the rest of the internet would have serious implications for their own speed test scores, because customers were encountering nightly slowdowns on popular websites like YouTube caused by overcongested connections. Company executives feared customers participating in the Sam Knows/FCC program would soon reveal Time Warner Cable’s internet speeds were beginning to suffer some of the same peak usage problems Cablevision was encountering in 2011. The executive’s solution? Temporarily expand upstream connections just long enough to protect Time Warner Cable’s broadband speed scores:

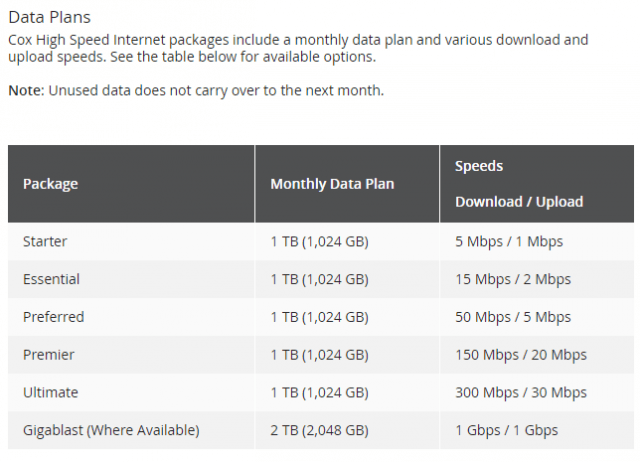

In an effort to keep up with Comcast, Cox Communications has quietly expanded its internet overcharging scheme to customers in Arkansas, Connecticut, Kansas, Omaha, Neb, and Sun Valley, Ida. (perhaps the only community that can afford Cox’s threatened overlimit fees). Cox’s customers have noticed and told DSL Reports about the

In an effort to keep up with Comcast, Cox Communications has quietly expanded its internet overcharging scheme to customers in Arkansas, Connecticut, Kansas, Omaha, Neb, and Sun Valley, Ida. (perhaps the only community that can afford Cox’s threatened overlimit fees). Cox’s customers have noticed and told DSL Reports about the

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment).”

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment).”

Even wireless providers have not stepped up. Efforts to encourage cellular companies to place antennas on the same towers used for the “white space” broadband experiment have failed as well. The newspaper reports the lack of population makes private providers “squeamish about expanding there.”

Even wireless providers have not stepped up. Efforts to encourage cellular companies to place antennas on the same towers used for the “white space” broadband experiment have failed as well. The newspaper reports the lack of population makes private providers “squeamish about expanding there.”

The bill could have been called the “Virginia Duopoly Protection Act,” because it only really allows public broadband development in unserved areas, and only after a community pays for a “broadband assessment” that the bill also mandates be sent to its potential competitors — private cable and telephone companies. Imagine if AT&T was required to send copies of their business plans to Comcast and Charter.

The bill could have been called the “Virginia Duopoly Protection Act,” because it only really allows public broadband development in unserved areas, and only after a community pays for a “broadband assessment” that the bill also mandates be sent to its potential competitors — private cable and telephone companies. Imagine if AT&T was required to send copies of their business plans to Comcast and Charter.

But wait, there is more:

But wait, there is more: