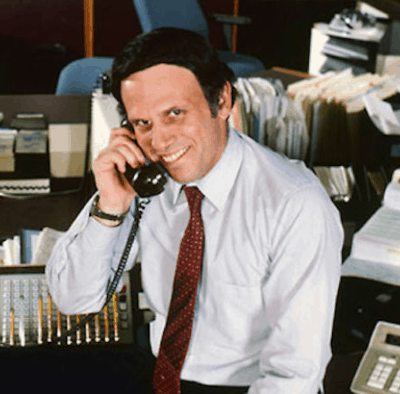

Milken in the 1980s (Image: The Gentleman’s Journal)

President Donald Trump granted clemency on Tuesday to Michael Milken, the so-called “junk bond king” who violated scores of securities and insider trading laws and was instrumental in helping finance the creation of America’s cable monopoly.

Milken used his position at the now-defunct Drexel Burnham Lambert to run its “high-yield bond unit.” More commonly known as “junk bonds,” these high-risk securities are typically issued by companies to finance mergers and acquisitions, often to strip assets or put competing companies out of business.

As a result, a new era of media and telecommunications tycoons emerged. Many successfully gained control of other companies and consolidated them into business empires, significantly reducing or eliminating serious competitors. Most of those companies still hold dominant positions today or have since merged with even larger companies. President Trump credited Milken for helping “create entire industries, such as wireless communications and cable television.”

By the late 1980s, Milken had advised scores of firms to rely on leveraged junk bond financing of corporate takeovers, a practice that endures to this day. Milken financed Rupert Murdoch’s ambitions to turn what was once a small newspaper chain into News Corp., which today still dominates in broadcasting, cable news channels like Fox News, and newspapers including the Wall Street Journal.

Milken also helped arrange financing for Craig McCaw, an early pioneer in cellular communications that leveraged cellular licenses McCaw borrowed heavily to obtain into one of the country’s first major wireless companies. But McCaw found bigger riches buying and selling mobile companies, first acquiring MCI’s cellular division in 1986 and selling his family’s cable operations to what would later become Comcast. By 1990, McCaw was the country’s highest paid CEO. Four years later, he sold McCaw Cellular to AT&T for $11.5 billion. AT&T sold that wireless company to Cingular in 2004 and then acquired Cingular itself some years later. McCaw would later plow $1.1 billion of family and borrowed money to take control of Nextel in 1995, only to sell it 11 years later to Sprint for $6.5 billion.

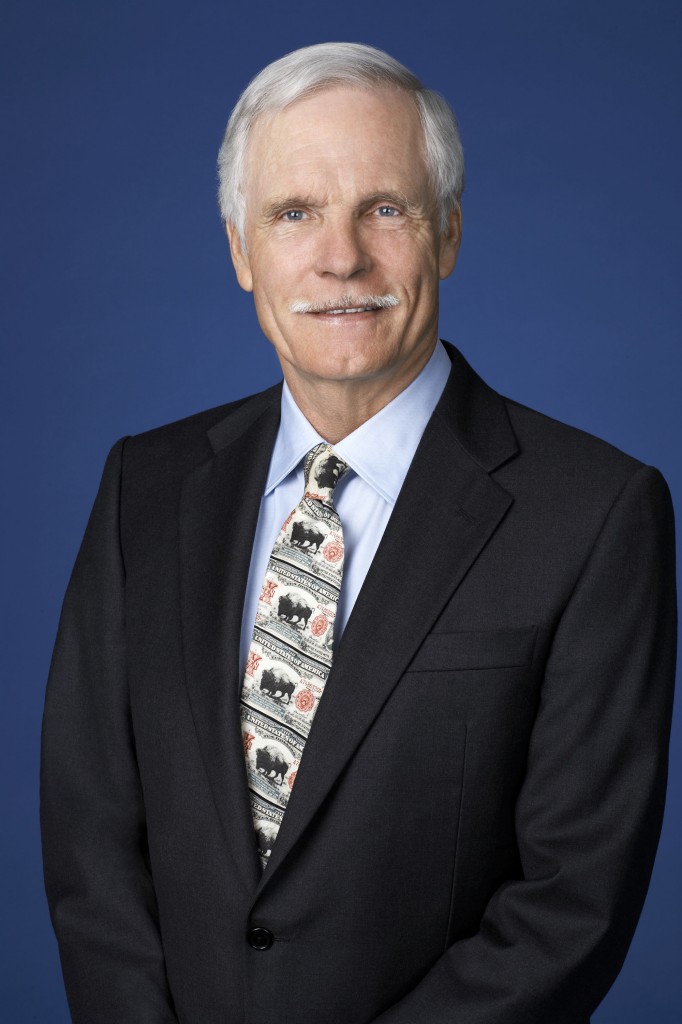

Malone

The country’s first cable giant, Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) would not have been possible without Milken’s junk bond financing scheme. Cable tycoon John Malone acquired hundreds of regional cable operators to create a cable empire that was often loathed by subscribers. TCI leveraged its position as a de facto monopoly, scaring off competitors, raising prices, and often delivering horrendous service. Vice President Al Gore would later characterize the Milken-financed emerging cable industry as a “cable Cosa Nostra,” and Malone himself as “Darth Vader.”

Time Warner’s cable division was also created as a result of a wave of consolidation that snapped up countless locally owned cable operators and smaller operators run by various media companies. Ted Turner also depended on Milken’s junk bond financing to create Turner Broadcasting, turning what was originally a single UHF independent TV station in Atlanta, Ga., into a superstation seen around the country and the launch of Cable News Network, better known as CNN.

Sometimes Milken’s clients benefited from his advice, sometimes they became targets themselves. Years after Turner Broadcasting was a major powerhouse in the cable programming business, Time Warner relied on a similar acquisition strategy to acquire Turner Broadcasting itself. Milken reportedly received a $50 million bonus for “advising” on the transaction, despite being in jail at the time. Years later, TBS founder Ted Turner would regret the buyout, which took CNN and TNT out of his hands.

Turner

Other household names from the past and present that expanded as a result of Milken’s financial advice include Viacom (now a part of CBS), MCI (embroiled in one of the country’s largest fraud schemes before being quietly sold off to Verizon), Telemundo (now effectively owned by Comcast), and Metromedia (which sold its network of popular independent TV stations to News Corp., which rechristened them FOX television network affiliates).

Milken quickly attracted the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which took years to build a case against the Wall Street star. It took arbitrageur Ivan Boesky to help bring Milken down after pleading guilty to securities fraud and insider trading. He ‘ratted out’ Milken, which prompted a major investigation of him and the investment firm he worked for.

Milken was eventually indicted for racketeering and securities fraud in 1989 and through a plea bargain, pleaded guilty to securities and reporting violations, which won him a reduced sentence. He was supposed to serve 10 years in jail, but was released after just 22 months for good behavior. He was also fined $600 million (later apparently reduced to $200 million), a fraction of his reported net worth of nearly $4 billion. Although Milken was permanently barred from the securities industry, he still received compensation from certain transactions after that ban, which raised eyebrows.

Critics claim Milken’s legacy emboldened Wall Street to engage in riskier behavior and to innovate new leveraging schemes. Some claim that eventually helped create the conditions leading to the 2008 Great Recession.

The president offered nothing but praise for Milken in his pardoning statement and claimed prosecutors were overzealous in pursuing Milken. The president received an earful of advice in favor of a presidential pardon from his Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, who is a close person friend of Milken and has flown on his private plane. Many Trump allies, including conservative powerhouse donors Sheldon and Miriam Adelson and property developer Richard LeFrak also lobbied the president on Milken’s behalf. So did the president’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, who ironically helped prosecute Milken in the 1980s. Some benefactors of Milken’s financial advice were also in favor of a pardon, including Rupert Murdoch.

Milken’s fans have been persistently seeking pardon relief for years. They failed to win a presidential pardon from former president Bill Clinton in 2001, after a joint letter strenuously objecting to the idea was sent from the SEC and U.S. attorney’s office in the Southern District of New York. The letter said pardoning Milken would “send the wrong message to Wall Street.”

Subscribe

Subscribe