“Devastating.”

“Devastating.”

“Too big to fix.”

“A bad, recurring dream.”

“An oligopoly.”

“A meritless merger.”

These were some of the comments from objectors to T-Mobile and Sprint’s desire to merge the two wireless carriers into one.

Consumer and industry groups filed comments largely opposed to the merger on the grounds it would be anti-competitive and lead to dramatic price increases for U.S. consumers facing a consolidated market of just three national wireless carriers.

Free Press submitted more than 6,000 signatures from a consumer petition opposed to the merger.

“This is like a bad recurring dream,” one of the comments said, reflecting on AT&T’s attempt to acquire T-Mobile in 2011.

The comments reflected consumer views that mergers in the telecom industry reduce choice and raise prices.

The comments reflected consumer views that mergers in the telecom industry reduce choice and raise prices.

The American Antitrust Institute rang alarm bells over the merger proposal it said was definitively against the public interest and probably illegal under antitrust laws. It declared two competitive harms: it creates a “tight oligopoly of the Big 3 and [raises] the risk of anticompetitive coordination” and it “eliminates head-to-head competition between Sprint and T-Mobile.”

The group found the alleged merger benefits offered by the two companies unconvincing.

“The claim that two wireless companies need a merger to expand or upgrade their networks to the next generation of technology is well worn and meritless. The argument did not hold any water when AT&T-T-Mobile advanced it in 2011 and the same is true here,” the group wrote. “The FCC should reject it, particularly in light of the merger’s presumptive illegality and almost certain anticompetitive and anti-consumer effects. Both AT&T and T-Mobile expanded their networks in the wake of their abandoned merger. And T-Mobile became a vigorous challenger to its larger rivals. Sprint-T-Mobile’s investor presentation notes, for example ‘T-Mobile deployed nationwide LTE twice as fast as Verizon and three times as fast as AT&T.’”

“The Sprint-T-Mobile merger is one of those mergers that is ‘too big to fix,’” the group added. “Like the abandoned AT&T-T-Mobile proposal, it is a 4-3 merger. It combines the third and fourth significant competitors in the market, creating a national market share for Sprint-T-Mobile of about 32%. Next in the lineup is AT&T, with a share of about 32%. Verizon follows with a share of about 35%. These three carriers would make up the vast majority (almost 99%) of the national U.S. wireless market with smaller MVNOs accounting for the remaining one percent. These carriers include TracPhone, Republic Wireless, and Jolt Mobile, Boost Mobile, and Cricket Wireless, which purchase access to wireless infrastructure such as cell towers and spectrum at wholesale from the large players and resell at retail to wireless subscribers.”

A filing from the groups Common Cause, Consumers Union, New America’s Open Technology Institute, Public Knowledge and Writers Guild of America West essentially agreed with the American Antitrust Institute’s findings, noting removing two market disruptive competitors by combining them into one would hurt novel wireless plans that are unlikely to be introduced by companies going forward.

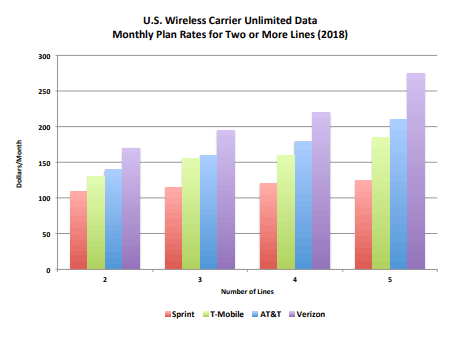

Rivals, especially AT&T and Verizon, have remained silent about the merger. That is not surprising, considering T-Mobile and Sprint have forced the two larger providers to match innovative service plans, bring back unlimited data, and reduce prices. A combined T-Mobile and Sprint would likely reduce competitive pressure and allow T-Mobile to comfortably charge nearly identical prices that AT&T and Verizon charge their customers.

Rivals, especially AT&T and Verizon, have remained silent about the merger. That is not surprising, considering T-Mobile and Sprint have forced the two larger providers to match innovative service plans, bring back unlimited data, and reduce prices. A combined T-Mobile and Sprint would likely reduce competitive pressure and allow T-Mobile to comfortably charge nearly identical prices that AT&T and Verizon charge their customers.

Smaller competitors are concerned. Rural areas have been largely ignored by T-Mobile, and Sprint’s modestly better rural coverage has resulted in affordable roaming arrangements with independent wireless companies. Sprint has favored reciprocal roaming agreements, allowing customers of independent carriers to roam on Sprint’s network and Sprint customers to roam on rural wireless networks. T-Mobile only permits rural customers to roam on its networks, while T-Mobile customers are locked out, to keep roaming costs low. Groups like NTCA and the Rural Wireless Association shared concerns that the merger could leave rural customers at a major disadvantage.

Many Wall Street analysts that witnessed the AT&T/T-Mobile merger flop are skeptical that regulators will allow the Sprint and T-Mobile merger to proceed. The risk of further consolidating the wireless industry, particularly after seeing T-Mobile’s newly aggressive competitive stance after the AT&T merger was declared dead, seems to prove opponents’ contentions that only competition will keep prices reasonable. Removing one of the two fiercest competitors in the wireless market could be a tragic mistake that would impact prices for a decade or more.

The American Antitrust Institute reminded regulators:

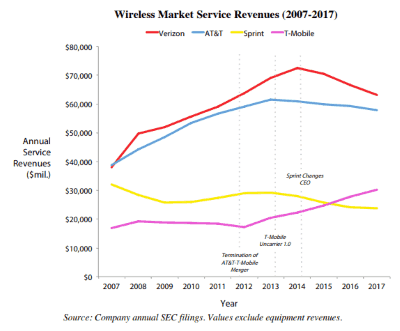

In 2002, there were seven national wireless carriers in the U.S.: AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, T-Mobile, Nextel, AllTel, and Cingular. In a consolidation spree that began in 2004, Cingular acquired AT&T. This was followed by Sprint’s acquisition of Nextel in 2005—a merger that has been called one of the “worst acquisitions ever.” At the time of the merger, Sprint and Nextel operated parallel networks using different technologies and maintained separate branding after the deal was consummated. The company lost millions of subscribers and revenue in subsequent years in the wake of this costly and confused strategy.

In 2009, Verizon bought All-Tel. This was followed by AT&T’s unsuccessful attempt to buy T-Mobile in 2011 and T-Mobile’s successful acquisition of mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) Metro PCS. The DOJ and the FCC forced the abandonment of the AT&T-T-Mobile deal. Like Sprint-T-Mobile, it was also a 4-3 merger that would have eliminated T-Mobile, a smaller, efficient, and innovative player that set the industry bar high for the remaining rivals.

AT&T’s rationale that the merger with T-Mobile was essential for expanding to the then-impending 4G LTE network technology also did not pass muster. In August of 2014, two years after the abandoned attempt, Forbes magazine concluded that there would have been “no wireless wars without the blocked AT&T-T-Mobile merger.”

Subscribe

Subscribe

I am against the T-mobile/Sprint merger for only one reason: Concentration of the limited, highly government controlled, Radio Spectrum in the hands of Three Players, rather than Four Players with National Footprints. If one could contact the government, tomorrow, and simply acquire Bandwidth on a national scale similar to any of the BIG FOUR, I’d agree the Sprint/T-mobile merger could move forward. Then, at least a fourth or fifth player could enter the market if the newly created BIG THREE exhibited pricing abuse related to their oligopoly power.