While rural western Massachusetts is stuck in a rural broadband swamp of Verizon’s making, politics in the state capital and governor’s office are risking Yankee ingenuity for another “free market” broadband solution that won’t solve the problem.

While rural western Massachusetts is stuck in a rural broadband swamp of Verizon’s making, politics in the state capital and governor’s office are risking Yankee ingenuity for another “free market” broadband solution that won’t solve the problem.

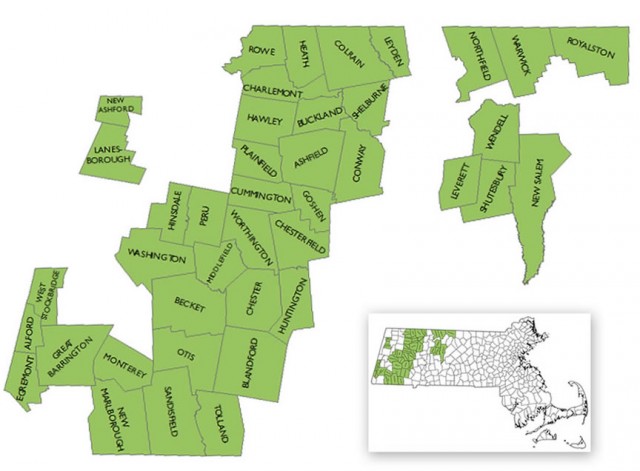

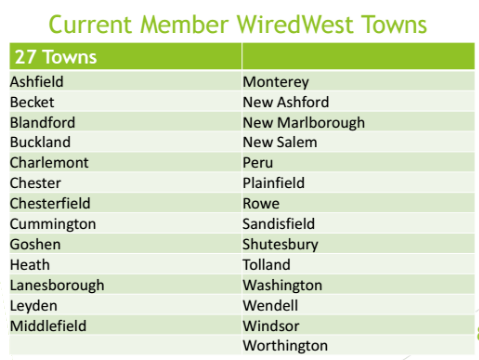

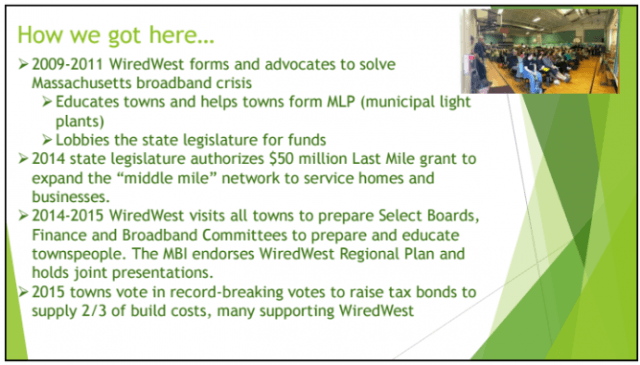

The dedicated locals that created WiredWest, the grassroots-envisioned regional broadband solution for more than two dozen towns suffering with inadequate or non-existent broadband service, have toiled for nearly a decade to accomplish what Verizon (or a cable operator) has never managed to do – provide consistently available internet access. WiredWest spent years carefully listening and learning the needs and challenges of each of their member towns. Communities affected by broadband deficiencies in this part of Massachusetts range from the most prosperous areas of the Berkshires to those financially struggling with a range of economic challenges.

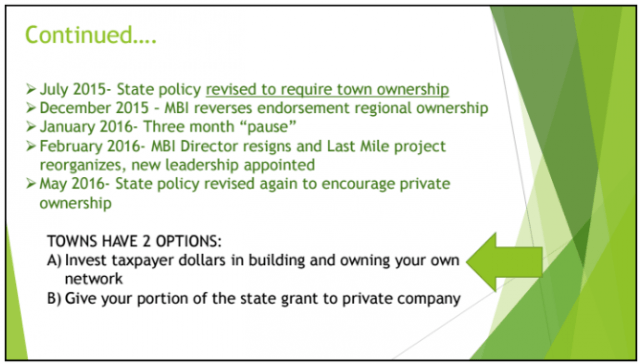

On August 13th, 2011, The WiredWest Cooperative in western Massachusetts was officially formed by charter member towns. The project has gained some town, lost some others as the region works towards faster broadband.

WiredWest’s original plan would have brought fiber broadband to practically everyone in the region in just a few years, with more prosperous and populous towns helping subsidize network construction costs for their more budget-challenged rural neighbors. The goal was to avoid the patchwork of broadband have’s and have not’s that many private providers have created across rural America.

Establishing a regional network instead of trying to launch dozens of smaller community-owned providers would help streamline costs, avoid duplicating services, and deliver continuity of service. The concept made plenty of sense to two dozen town leaders and the participating communities, most voting to support the regional approach. But it apparently didn’t seem to make a lot of sense to a bureaucratic state agency called the Massachusetts Broadband Institute (MBI) that suddenly questioned the project’s operating plan and has avoided releasing tens of millions of dollars stashed in its bank account designated for rural broadband network construction.

MBI’s detractors call the agency a “concern troll” and some question whether MBI’s objections are the result of the usual friction between out-of-touch state bureaucrats and the rural communities they are supposed to help, or something more insidious. Others are content stating MBI’s position simply does not make any sense.

MBI spent more than a million dollars of taxpayer funds on lawyers and a Bangalore, India-based consultancy to produce and defend a dubious hit piece “analysis” about WiredWest rife with misconceptions and factual errors. The MBI-sponsored report concluded WiredWest would simply never work. What works better for MBI is handing out $4 million in taxpayer dollars to Comcast, with tens of millions more to be spent on funding private rural broadband projects in the future.

Crawford

Earlier this month, broadcast activist Susan Crawford shared her blistering conclusions about the usefulness of MBI:

For an agency that has produced virtually nothing so far, MBI is a high-priced operation. As far as I can tell, last year MBI spent $1 million of those state funds on consultants, lawyers, and administrative costs in order to hand $4 million to Comcast to provide its usual service to about a thousand homes in those nine Massachusetts towns that already had some cable service. What’s odd is that MBI told the public it chose Comcast because the company had vast experience and could get the work done without involving MBI—so it cost $1 million in oversight expenses to choose a company that doesn’t need oversight.

Despite protests from many residents across WiredWest’s would-be service area, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker sided with his bureaucrats and stalled rural broadband deployment further with a temporary hold, which some claimed gave MBI and community broadband opponents additional time to further undermine WiredWest’s efforts.

Despite protests from many residents across WiredWest’s would-be service area, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker sided with his bureaucrats and stalled rural broadband deployment further with a temporary hold, which some claimed gave MBI and community broadband opponents additional time to further undermine WiredWest’s efforts.

Most recently, the same agency that wrung its hands worrying about the efficacy of WiredWest had no problem offering a quick $20 million in grants to private companies for rural broadband solutions. Few in broadband-challenged western Massachusetts are likely to be happy about the results of the latest machinations of MBI’s “free market solution with public taxpayer funds.” Last week, the public got its first look at the submitted applications, largely underwhelming in scope and specifics. None come close to offering the kind of ubiquitous and affordable broadband WiredWest proposed.

MBI also tailored their request for proposals to arbitrarily limit applicants, declaring only companies with $100 million in yearly revenue and at least five years experience building, operating, and maintaining residential broadband networks need apply. Had Google Fiber proposed to wire the entire region with fiber optics in an application, MBI would have turned Google down for lack of experience. (Google Fiber launched service in late 2012.) In fact, no startup or municipal project of any kind could realistically apply. Comcast and Charter could, and both did.

MBI claims each town will make their own final decision, but many communities have already done that by choosing WiredWest. Some towns are frustrated by the state’s interminable delays and politics and are discouraged with the potential spectacle of MBI continuing to throw up roadblocks for political reasons. Those communities are planning their own alternative projects if WiredWest can never get off the ground. The only current alternative is hoping a private company will step up and deliver service. Six applicants responded to MBI’s request for proposals from private providers. Only two showed any willingness to offer service across all of broadband-challenged western and central Massachusetts. Two others were cable operators that have neglected expanding service on their own because it was not profitable to do so. Another two applicants only wanted to serve a handful of communities. Here is an overview of the proposals:

Crocker Communications: Short on specifics, Crocker’s proposal claims an interest in wiring almost 40 unserved communities for $59.15 million, including $18.33 million in taxpayer funds, split into individual grants for each community. But even Crocker, among the most ambitious and detailed applicants, cannot meet MBI’s revenue qualifications, so it attempts to claim a vendor relationship with Fujitsu Network Communications of Japan, which supplies network infrastructure. How Fujitsu would be financially involved in the project to minimize the chances of Crocker running into financial problems while building out its proposed network is not adequately explained. Crocker only specifies $5 million of its own assets will be on the line.

Crocker Communications: Short on specifics, Crocker’s proposal claims an interest in wiring almost 40 unserved communities for $59.15 million, including $18.33 million in taxpayer funds, split into individual grants for each community. But even Crocker, among the most ambitious and detailed applicants, cannot meet MBI’s revenue qualifications, so it attempts to claim a vendor relationship with Fujitsu Network Communications of Japan, which supplies network infrastructure. How Fujitsu would be financially involved in the project to minimize the chances of Crocker running into financial problems while building out its proposed network is not adequately explained. Crocker only specifies $5 million of its own assets will be on the line.

Crocker’s website promotes the company’s desire to have a bigger presence in the state thanks to its cooperation with MBI. Crocker currently provides internet service to customers of a Leverett-based community broadband project. Coincidentally, Peter d’Errico of Leverett’s Broadband Committee was one of the contributors to MBI’s sponsored report slamming the WiredWest project as unrealistic and underfunded. We’re not sure what d’Errico thinks about Crocker Communications’ proposal, which asks for grants as little as $150,000 to help wire one community — New Ashford.

In an aspirational executive summary, Matthew Crocker, president of Crocker Communications, offers an admission there are “inherent challenges in fulfilling the Request For Proposals.” His conclusion: “If this were easy, it would be well underway.”

Crocker’s proposal won’t be easy for roughly 30% of those living in the nearly 40 communities his company proposes to serve. That’s because his company won’t be serving them. Crocker’s proposal only suggests he will deliver service to about 70% of the service area. MBI wanted proposals that would reach 96% of the population. But there will be plenty of time to contemplate these points. Crocker’s proposal warns residents may have to wait until 2021 before they can get service. That will give would-be customers four years to save enough money to pay Crocker’s proposed installation fees: “under $2,000 for 70% of homes passed” or “$3,000 for 96% of homes passed.” Ouch.

Crocker’s proposal won’t be easy for roughly 30% of those living in the nearly 40 communities his company proposes to serve. That’s because his company won’t be serving them. Crocker’s proposal only suggests he will deliver service to about 70% of the service area. MBI wanted proposals that would reach 96% of the population. But there will be plenty of time to contemplate these points. Crocker’s proposal warns residents may have to wait until 2021 before they can get service. That will give would-be customers four years to save enough money to pay Crocker’s proposed installation fees: “under $2,000 for 70% of homes passed” or “$3,000 for 96% of homes passed.” Ouch.

Whip City Fiber: Even more murky than Crocker Communications’ proposal, Westfield Gas & Electric’s “Whip City” fiber service submitted a plan offering to serve any of the 40 communities MBI identifies as underserved, but the details aren’t there, except to describe the service the company already provides to its own customers. The actual number of towns to be served and the schedule to launch service are all: TBD = To Be Determined.

Mid-Hudson Data: The most modest of proposals from this Catskill, N.Y. based company seeks $260,000 to offer 279 homes fiber service and wireless for another 20 in the community of Tyringham. Customers would pay an installation fee of $150. While potentially good news for customer living near George Cannon Road, it isn’t much help to the rest of the region.

Mid-Hudson Data: The most modest of proposals from this Catskill, N.Y. based company seeks $260,000 to offer 279 homes fiber service and wireless for another 20 in the community of Tyringham. Customers would pay an installation fee of $150. While potentially good news for customer living near George Cannon Road, it isn’t much help to the rest of the region.

Fiber Connect, LLC: Another modest proposal from this regionally based ISP offers to provide broadband service for Alford, Becket, New Marlborough, Otis, Tolland and Tyringham. The proposal notes the company is already running a pilot broadband program in Monterey and Egremont. One potential stumbling block is a poorly explained installation fee ranging from $0 if municipalities agree to a “fixed average cost” that could be included in grant funding or a municipally guaranteed lease-to-own payment to $299 if a customers apply for a mysterious promotion or rebate, or $999 which is defined as the basic “initial installation cost.”

Fiber Connect, LLC: Another modest proposal from this regionally based ISP offers to provide broadband service for Alford, Becket, New Marlborough, Otis, Tolland and Tyringham. The proposal notes the company is already running a pilot broadband program in Monterey and Egremont. One potential stumbling block is a poorly explained installation fee ranging from $0 if municipalities agree to a “fixed average cost” that could be included in grant funding or a municipally guaranteed lease-to-own payment to $299 if a customers apply for a mysterious promotion or rebate, or $999 which is defined as the basic “initial installation cost.”

Charter Communications: Formerly Time Warner Cable, Charter is hunting for taxpayer-funded grants to expand broadband service to Egremont, Hancock, Monterey, New Salem, Princeton and Shutesbury. All of those communities are near existing Charter/Time Warner Cable systems and the company spared no time in their application promoting their existing close ties with MBI to bring broadband to Hinsdale, Lanesborough, and West Stockbridge. Charter claims it can expand its cable service into the nearby communities in a “reasonable amount of time” but does not get more specific than that.

Charter Communications: Formerly Time Warner Cable, Charter is hunting for taxpayer-funded grants to expand broadband service to Egremont, Hancock, Monterey, New Salem, Princeton and Shutesbury. All of those communities are near existing Charter/Time Warner Cable systems and the company spared no time in their application promoting their existing close ties with MBI to bring broadband to Hinsdale, Lanesborough, and West Stockbridge. Charter claims it can expand its cable service into the nearby communities in a “reasonable amount of time” but does not get more specific than that.

Comcast: Boils down its application to “we’re doing you a favor, but you pay” language reminding MBI the communities Comcast now proposes to serve: Goshen, Montgomery, Princeton and Shutesbury don’t come close to Comcast’s demand for return on its investment. But since taxpayers are helping to foot the bill….

Comcast: Boils down its application to “we’re doing you a favor, but you pay” language reminding MBI the communities Comcast now proposes to serve: Goshen, Montgomery, Princeton and Shutesbury don’t come close to Comcast’s demand for return on its investment. But since taxpayers are helping to foot the bill….

The one noticeable difference Comcast has over all the rest of the applicants is a page-and-a-half of details about the various regulator-imposed fines and penalties it has had to pay recently for being an ongoing menace to its own customers. Is it arrogance for a company to assume such a vast number of damaging disclosures would not lead a responsible grantor to put the application in the circular file, or is it something else? After all, Comcast was already awarded up to $4 million in taxpayer funds in Massachusetts as a gushing press release reported in August, 2016:

WESTBOROUGH – The Massachusetts Broadband Institute at MassTech (MBI) and Comcast have reached an agreement that will extend broadband access in nine municipalities in Western and North Central Massachusetts, a project which is estimated to deliver broadband connectivity to 1,089 new residences and businesses, and will bring the overall coverage level in each town to 96% or above. The grant will provide up to $4 million in state funds to reimburse partial project costs for Comcast, which has existing networks in each of the towns, to construct broadband internet extensions to additional homes and businesses.

“This agreement further demonstrates our administration’s commitment to tackling broadband connectivity challenges for unserved residents and businesses,” said Governor Charlie Baker. “This public-private partnership will deliver sustainable, reliable, and cost-effective broadband connectivity to nine rural communities that previously faced significant coverage gaps, allowing nearly 1,100 households and businesses to participate more fully in the digital economy.”

“Our results-oriented approach to bridging broadband access gaps is connecting thousands of rural residents to the modern internet,” said Lieutenant Governor Karyn Polito. “We will continue to employ a dynamic, flexible approach to the Last Mile project, and seek solutions that meet the unique needs of communities and residents unserved by broadband access.”

The construction of the broadband extensions in Buckland, Conway, Chester, Hardwick, Huntington, Montague, Northfield, Pelham, and Shelburne is estimated to be completed within two years from the start of the project. The public-private partnership will extend high-speed internet service to unserved residents at speeds that meet or exceed the FCC’s definition of broadband service, through a hybrid fiber/coaxial-cable network.

Wired West Responds With a New Plan

Faced with insurmountable political obstacles, the folks behind WiredWest have bowed to the reality of the current political landscape and reintroduced themselves and their newest plan to get western Massachusetts wired for fiber optic broadband while trying to avoid any further encounters with MBI’s speed bumps and obstacles.

If WiredWest made one mistake, it was forgetting to establish the one connection that apparently matters more than anything else in Massachusetts: a political connection with state lawmakers. But the indefatigable group has not given up, and if the MBI is being honest about being an impartial partner in improving rural broadband in Massachusetts, there is still a better option available to communities than the six proposals recently submitted to MBI. That option is WiredWest.

In its latest proposal WiredWest would continue to play a significant role in the network after being built, with proven service plans that will deliver real broadband service to residents at rates comparable to what private companies charge. But the project will rely on member towns to construct their own fiber networks using private contractors and state and local funding. That puts more responsibility and network ownership in the hands of each individual town, an idea some towns originally rejected as too expensive and cumbersome. But MBI holds the money and has apparently rewritten the rules, so what MBI wants is what MBI will get.

The added cost to the project and the communities involved is significant: there will be some towns that cannot afford or manage the responsibility of constructing their own fiber networks and will likely drop out of the project. The new network plan will also increase costs WiredWest originally hoped to avoid. The group’s financial model also effectively subsidized some of the costs for the smallest and least able communities — a model that could be gone for good.

Each participating town network that does eventually get built will be connected in a ring topology to MassBroadband123, the state’s “middle mile” fiber network that is run privately by Axia Networks. At this point, it appears 14 communities are still on board with WiredWest, seven are “considering” the new WiredWest plan, and another 16 are “pursuing other options” but have not ruled out staying with WiredWest.

It is our recommendation that communities do everything possible to stay loyal to WiredWest, which has a proven track record of being responsive and accessible to communities across the region. Bucking the state’s inexcusable political interference by remaining united sends a strong message that local communities know best what they need, not a high-priced consultant, Springfield-based lawyers and bureaucrats, or the governor. None of those people have to live with the consequences of inferior or non-existent broadband and none have given the problem the kind of serious attention WiredWest has. The biggest challenge to WiredWest isn’t its financial sustainability, it is politics, and that needs to stop.

We’ve reviewed the submissions from MBI’s latest round of grant funding for private projects and they are all inadequate. While many of the companies involved are well-meaning and we believe could play a role in improving rural broadband, most of the applications seem to have been rushed and many lack specifics.

We’ve reviewed the submissions from MBI’s latest round of grant funding for private projects and they are all inadequate. While many of the companies involved are well-meaning and we believe could play a role in improving rural broadband, most of the applications seem to have been rushed and many lack specifics.

The region should not accept any plan offering only 70% broadband coverage, much less a proposal that will force another four-year wait for broadband (we credit Crocker Communications for at least including a specific timetable, something many of the other proposals did not.) Installation fees up to $3,000 are also unaffordable, with or without a financing plan.

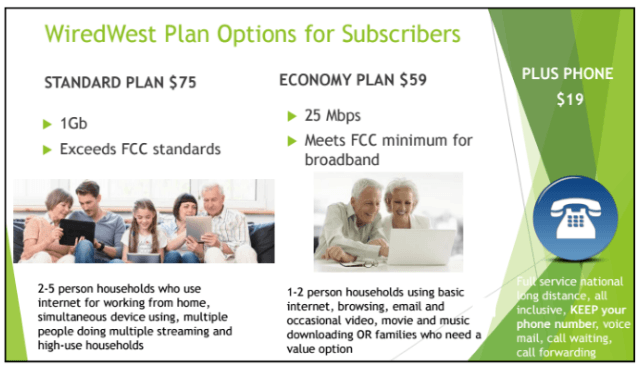

Some analysts still worry if WiredWest can attract enough customers to be sustainable. If it isn’t, most of the private projects MBI has received applications for certainly are not either. Assuming customers can afford a few thousand dollars for installation — a major impediment to getting new customers, there is no guarantee which homes will get service and when. Competitively speaking, considering the only available alternative in most cases is spotty 1-6Mbps DSL from Verizon — a service the company has lost interest in improving or expanding — Verizon is likely to receive the same treatment it gets in other communities where better alternatives exist — a mass exodus of customers cutting Verizon’s cord for good. In fact, Verizon may ultimately sell its landline network in western Massachusetts to another company as it continues to disengage from its wireline businesses. It is highly unlikely any competitor of WiredWest will guarantee access to at least 25Mbps broadband.

WiredWest proposes to charge $59 for 25Mbps or $75 for 1,000Mbps broadband. Digital phone service is $19 a month. An installation fee of $99 will also apply. That is not out of line with what cable companies and other gigabit providers have charged, and they have won a comfortable market share. Private cable and phone companies also continue to raise rates on broadband, if only because they can, providing additional competitive insulation.

MBI’s grants should also not be the end of the story. New York last week rescued up to $170 million from the FCC’s Connect America Fund (CAF) to expand broadband deployment in unserved rural areas of New York State — money Verizon forfeited by expressing no interest in rural broadband expansion. That precedent opens the door for other states to recapture similar federal grants, including those that could target western Massachusetts where Verizon has also declined to accept CAF money. That could ease some of the money worries about WiredWest’s construction costs as well.

At the end of the day, area residents have turned up repeatedly at various events across the region holding signs supporting their choice in local providers: WiredWest. Nobody was holding up a sign hoping Comcast or Charter would be the company that finally brings broadband to their communities. The irony of using taxpayer dollars to fund Comcast in particular is not lost on their customers — many that loathe the company and wish they had another choice. Handing $20 million to that cable giant to expand in western Massachusetts guarantees their newest customers won’t have a choice either. Isn’t it time to give these communities what they want? They clearly want WiredWest.

Subscribe

Subscribe