When the community of Batavia, Ill., a distant suburb of Chicago, decided they wanted something better than the poor broadband offered by Comcast and what is today AT&T, it decided to hold a public referendum on whether the town should construct and run its own fiber to the home network for the benefit of area residents and businesses. A local community group, Fiber for Our Future, put up $4,325 to promote the initiative back in 2004, if only because the town obviously couldn’t spend tax dollars to advertise or promote the idea itself.

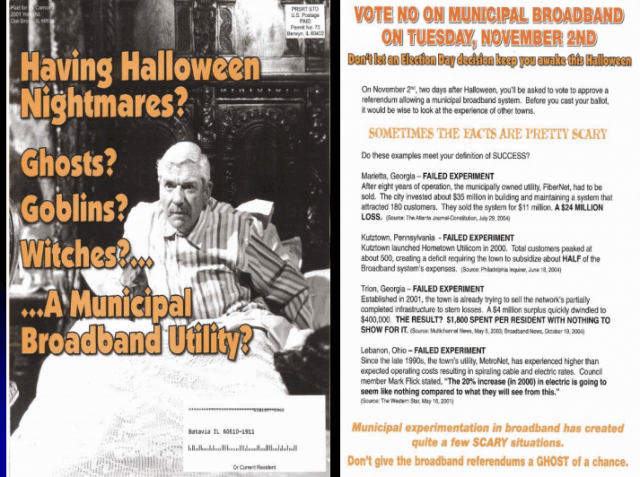

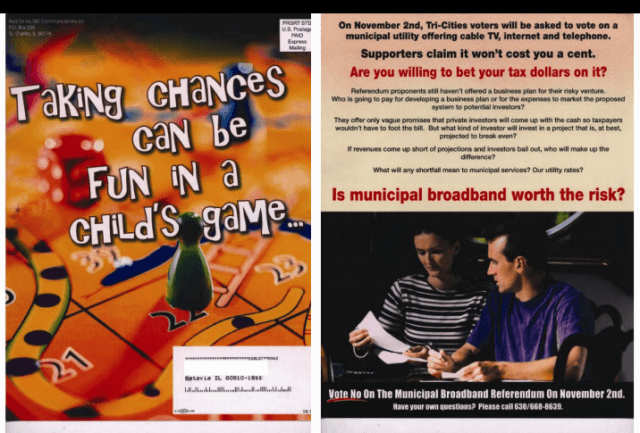

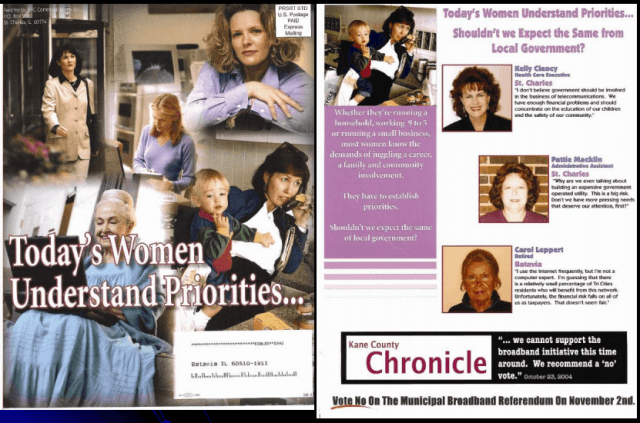

Within weeks of the announced proposal, both Comcast and SBC Communications (which later acquired AT&T) launched an all-out war on the idea of fiber to the home service, mass mailing flyers attacking the proposal to area residents and paying for push polling operations that asked area residents questions like, “should tax money be allowed to provide pornographic movies for residents?” The predictable opposition measured in response to questions like that later appeared in mysterious opinion pieces published in area newspapers submitted by the incumbent companies and their allies.

Comcast spent $89,740 trying to defeat the measure in a community of just 26,000 people. SBC spent $192,324 — almost $3.50 per resident by Comcast and just shy of $7.50 per resident by SBC. Much the same happened in the neighboring communities of St. Charles and Geneva.

According to Motherboard, the scare tactics worked, cutting support for the fiber network from over 72 percent to its eventual defeat in two separate referendums, leaving most of Batavia with 3Mbps DSL from SBC or an average of 6Mbps from Comcast.

Much of the blizzard of mailers and brochures Comcast and SBC mailed out were part of a coordinated disinformation campaign. Both companies also knew their claims would go largely unchallenged because Fiber for Our Future and other fiber proponents lacked the funding to respond with fact check pieces of their own mailed to residents to expose the distortions.

When it was all over, it was back to business as usual with Comcast and SBC. The latter defended its reputation after complaints soared about its inadequate broadband speeds.

Kirk Brannock, then midwest networking president for SBC, told city council members in the area that “fiber is an unproven technology.”

“What are you going to do with 20Mbps? It’s like having an Indy race car and you don’t have the racetrack to drive it on. We are going to be offering 3Mbps. Most users won’t use that,” he said.

“All the subscribers got these extraordinary fliers. Ghosts, goblins, witches. I mean, this is about a broadband utility. Very scary stuff. This is real. This is comical, but this is very real,” Catharine Rice of the Coalition for Local Internet Choice said of the fliers at an event discussing municipal fiber earlier this year. “They have this amazing picture, and then they lie about what happened. They’re piling in facts that aren’t true.”

In communities that won approval for construction of publicly-owned fiber networks, the battle wasn’t over. Tennessee’s large state cable lobbying group unsuccessfully sued EPB to keep it out of the fiber business. In North Carolina, Time Warner Cable effectively wrote legislation introduced and passed by the Republican-dominated General Assembly that forbade community broadband expansion and made constructing new networks nearly impossible. In Ohio, another cable industry-sponsored piece of legislation destroyed the business plan of Lebanon’s fiber network, forcing the community to eventually sell the network at a loss to Cincinnati Bell.

The larger Comcast grows, the more financial resources it can bring to bare against any would-be competitors. Even in 2004, the company was large enough to force would-be community competitors to steer clear and stay out of its territory.

Subscribe

Subscribe