Alltel's logo, in use before 2006

Alltel Wireless is back. Two years after Alltel was bought by Verizon Wireless, some 900,000 customers in Georgia, Illinois, North and South Carolina, Ohio and Idaho not included in the transition to Verizon will remain Alltel customers under new management.

For many customers, that suits them just fine. In fact, with an increasing number of complaints from the 13.2 million former Alltel customers forced into a shotgun cellular wedding with Verizon or AT&T, many wish they could have the choice to return to Alltel themselves.

The demise of Alltel is another classic example of a telecommunications deal that made sense (and dollars) for Wall Street and a handful of Alltel executives, but left thousands of employees out in the cold in the unemployment line and customers coping with broken promises and higher bills.

It’s a story familiar to most of our readers, because the game plan for most telecom mergers and acquisitions delivers all of the benefits to a select few and ends up costing consumers plenty. That these deals get almost routine approval from the Federal Communications Commission is ironic, considering that same agency commissioned studies that unsurprisingly found increased consolidation and lack of competition in the wireless marketplace.

The end of Alltel is a great example of what happens when an industry achieves near-total deregulation. Lobbyists sell deregulation as directly benefiting consumers with increased competition, more innovation, and lower prices. In reality, from broadcasting to broadband, deregulation sparks escalating rounds of mergers, acquisitions, and buyouts. Wall Street doesn’t want increased competition — it wants fewer options, less costly innovation, and higher prices to sustain profits. When Wall Street speaks, most of these companies listen.

Since 1996, when the Telecommunications Act was passed, more than two dozen telecommunications companies have been swallowed up in mergers and buyouts. Consumers find themselves with new providers and higher bills. But not everyone is hurting from laissez-faire tele-economics. For a handful of top executives, the result has been riches beyond their wildest dreams. Even when they are forced out through merger deals, the golden parachutes that follow brings tears of joy. Just ask Alltel’s last CEO — Scott T. Ford — he said goodbye to Alltel in 2007 with a parting bonus of nearly $150 million dollars.

Alltel’s History — Keeping It In the Family

Alltel’s history in the telephone business traces all the way back to 1943, with the formation of the Allied Telephone Company of Little Rock, Arkansas. Back then, telephone service in the U.S. was mostly a monopoly of AT&T and several smaller independent phone companies. Allied’s business began as a pole and wiring provider for those phone companies. In 1983, Alltel – the traditional phone company – was created from a merger between Allied Telephone and Mid-Continent Telephone. In 1985, Alltel Wireless service began from its first cellular system in Charlotte, N.C. In less than a decade, the wireless division would expand service in smaller cities and towns across mid-America and the south, often where larger carriers didn’t want to provide service.

Just about everything in the telecommunications industry changed with the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton. The law that promised to open the doors to better service and more competition actually deregulated most of the industry into an “anything-goes” circus of money-fueled mergers, buyouts, and consolidation. Important consumer protections were discarded along the way.

The implications of the Act were well understood by corporate executives in the industry, and companies spent millions to lobby for its passage. They considered it a down-payment for better days to come. The biography of Alltel’s then-CEO Joe T. Ford noted the passage of the law changed everything, even leading to a violation of an agreement he made with his son when he was only 12 years old:

Scott T. Ford, the president and chief executive officer of the Alltel Corporation, made his first business deal at the age of 12 with his father, Joe T. Ford. The two agreed that Scott would never work at Alltel. Joe wanted to spare his son what he himself had endured since coming to work for his father-inlaw, Hugh Wilbourne Jr., in 1959. After the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, however, the Fords rethought their agreement, and, at age 35, Scott Ford became executive vice president of Alltel. Within two years he was appointed CEO, following in the footsteps of his grandfather Wilbourne, who formed Allied Telephone Company in 1943 in Little Rock, Arkansas.

All that hard work by earlier generations was about to pay some serious dividends in a laissez-faire telecommunications world.

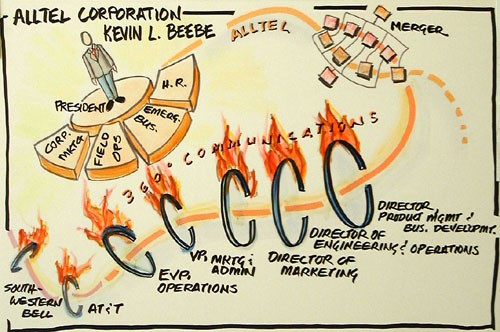

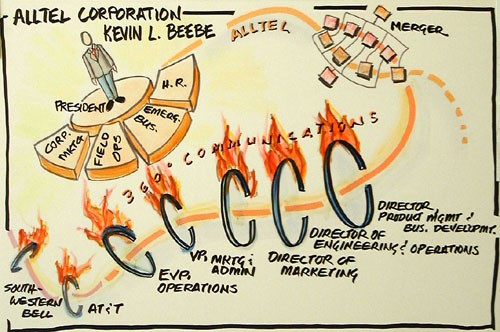

Beebe literally drew his own road map depicting his idea of success - remaining on top after a flurry of mergers and ongoing industry consolidation

The Dot.com Boom… for Some

At the end of the 20th century, the telecommunications industry was in the middle of the dot.com boom.

The impact of the 1996 Telecom Act did fuel change among traditional telecom companies. While some new players were wildly upgrading networks and building fiber optic networks to sustain the dot.com book, most of the traditional phone and cable companies were spending their time and attention on mergers and leveraged buyouts. The Baby Bell-AT&T empire that was broken up in the mid-1980s was nearly restored to its former glory with super-sized Verizon and AT&T. Independent phone companies which operated for a century were suddenly the targets of buyouts, now consolidated by regional players like CenturyTel, Embarq, Alltel and Citizens.

Alltel didn’t just buy up other independent phone companies. It also bought wireless providers and soon merged its landline and wireless divisions into a single company. This was the era when the “full service phone company” was trendy — capable of delivering local, long distance, and wireless service all from one company, usually on one bill.

Alltel’s executives, like then-Alltel group president Kevin Beebe, delivered presentations to Wall Street bankers like Credit Suisse/First Boston promoting Alltel and its made-for-consolidation balance sheet. He literally drew his own road map showing his route to success, depicting himself on top after successive mergers with smaller players.

Unfortunately, the high-powered, cash rich days of the dot.com deal were about to end. By the start of the new century, it was all over. An oversupply of infrastructure was built to support web-based businesses that would never launch. Many of those already in business shuttered their virtual doors. Venture capital for telecommunications projects dried up. But there was still plenty of money to be made in wireless, and Alltel did obtain financing to launch mergers and buyouts with as many small cell phone providers as possible. By the early 2000s, the mentality in the telecommunications business was “small is bad.” The only path to success was to buy your competition, or be bought by them.

The business of mergers and acquisitions earned countless millions for Wall Street banks, who charged fees to help structure the deals and usually helped finance them. Executives always won, even if a merger brought an end to their career at the company. Golden parachutes kept the top floor happy. The only losers were the soon-to-be-ex-employees and middle management declared redundant and escorted from the building. They were the “cost savings” promoted as a benefit of the merger months earlier. Meanwhile, customers were stuck dealing with the transition changes, service interruptions, and the eventually higher bill that always result from reduced competition.

During the first half of this decade, it was Alltel doing the acquiring — spending fortunes to acquire other regional wireless phone companies:

- 2002: Alltel acquires 700,000 wireless customers from CenturyTel Inc. in Arkansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Texas and Wisconsin for $1.5 billion.

- 2003: Alltel purchases wireless properties in Mississippi from Cellular XL.

- 2004: Alltel acquires wireless properties from MobileTel, U.S. Cellular and TDS Telecom.

- 2005: Alltel merges with Western Wireless Corp., acquires wireless properties from Public Service Cellular, certain wireless assets from Cingular and exchanges properties with U.S. Cellular of Chicago to meet divestiture requirements related to Alltel’s merger with Western Wireless Corp. Alltel agrees to purchase Midwest Wireless for $1 billion in cash.

Despite the shopping spree, Alltel’s executives like Beebe continued to let it be known Alltel itself was “well-positioned for wireless consolidation” — available for a buyout… for the right price. By 2006, Alltel had become the fifth largest telecommunications company in the country, with operations in 34 states. Thanks to lengthy roaming agreements with Sprint and Verizon Wireless, Alltel could deliver national service even from a regional network.

Alltel also enjoyed a satisfied customer base, thanks to innovative calling plans and services that were unheard of from other cell companies. In 2006, it introduced the popular My Circle calling plan, which allowed customers to make unlimited wireless calls to up to ten numbers, regardless of whether they were landlines or other Alltel wireless customers. That same year, U Prepaid was introduced, which included unlimited calling and text messaging to a pre-designated number — perfect for those needing to call home. Alltel prepaid customers could also roam on many other carrier’s networks without paying enormous roaming fees.

Alltel Sells Out Its Landlines

Until the 1996 Telecom Act, most publicly-owned telephone companies were considered a safe utility stock. In rural communities, many of the phone companies that established service where AT&T’s Bell System did not have been around since the 1890s. Often owned by a family or cooperative, these independent phone companies popped up when Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone patents expired. The companies were hardly growth hotbeds, traditionally serving communities that saw little growth and lots of expenses from the wide-open country they had to wire.

After deregulation, venture capital moved aggressively into the wireless and cable sectors. For the first time, many rural phone companies faced competition from rural cellular providers and cable companies experimenting with “digital phone” service delivered over cable television lines. But unlike the phone company, these providers were not required to deliver service to everyone. Most of these services would only challenge the phone company in population centers within towns and villages, that also happened to be where most of their customers lived and worked.

After deregulation, venture capital moved aggressively into the wireless and cable sectors. For the first time, many rural phone companies faced competition from rural cellular providers and cable companies experimenting with “digital phone” service delivered over cable television lines. But unlike the phone company, these providers were not required to deliver service to everyone. Most of these services would only challenge the phone company in population centers within towns and villages, that also happened to be where most of their customers lived and worked.

The business model was changing. As rural phone companies began losing customers to cable and wireless providers, some of them looked to mergers and acquisitions to reduce costs and improve revenues to keep revenue stable, even as customers disconnected. To maintain interest and investment from stockholders, many traditional publicly-held phone companies began paying shareholders increased dividends, which attracted attention from Wall Street.

On July 11, 2004, one independent phone company set a new bar for dividends and probably changed the long term business models of rural phone companies for years to come. Citizens Communications Corporation, as part of a corporate re-shuffle, announced the resignation of its then-CEO Leonard Tow, changed its name to Frontier Communications, and announced an incredible one-time payout of a $2 dividend for every share of common stock, and an ongoing annual $1 dividend, payable every quarter.

With a payout like that, investors began demanding increasing dividends from other phone companies, Alltel included. To pay that kind of dividend, you need revenue, and slow-growth rural phone companies cannot just generate millions in new revenue selling voicemail, long distance plans, and caller-ID. That kind of money comes from new lines of business, such as broadband, or from cash-generating mergers and buyouts.

Broadband required millions of dollars in new investments, increasing short term costs and having to wait several years to see a return. Mergers and acquisitions delivered fast cash and instant results — short term benefits Wall Street loves to see.

So while phone companies continued to lose landline customers at rates up to 7 percent per year, another round of frenzied consolidation through mergers and buyouts erupted.

Rural Phone Company Deals

|

From 2004 forward, an explosion in mergers and acquisitions tempered only by a shrinking number of available targets by 2009 led to more than two dozen consolidations among independent phone companies. (Source: Stifel, Nicolaus & Company)

|

|

Year

|

No. of deals

|

Deal value [in millions of dollars]

|

|

2004

|

2

|

527

|

|

2005

|

4

|

9,100

|

|

2006

|

6

|

2,196

|

|

2007

|

13

|

4,110

|

|

2008

|

7

|

11,880

|

|

2009

|

3

|

8,930

|

For Alltel, already established with a strong wireless division, seeing the long term prospects of trying to sustain its landline business as it lost customers seemed pointless. In December 2005, Alltel announced it was dumping its 3,000,000 landline customers, combining them with another 500,000 customers of Irving, Texas-based Valor Communications in a $9.1 billion dollar tax-free deal to create a new independent landline company — Windstream Communications.

Alltel would henceforth be a wireless phone company-only, and a much richer one at that. Unfortunately, despite its ranking as America’s fifth largest wireless provider, Alltel still remained a regional player, far behind its fourth largest rival T-Mobile. With a dwindling number of wireless companies to acquire, speculation grew Alltel itself would soon become a takeover target.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/KLRT Little Rock Alltel Sold to Goldman Sachs 5-20-07.flv[/flv]

KLRT-TV in Little Rock covered the announced acquisition of Alltel by Goldman Sachs on May 20, 2007 in these three reports. (15 minutes)

Goldman Sachs Moves In

Within two years, Alltel’s independence would come to an end. In 2007, Alltel formally opened an auction to sell the company’s wireless assets to the highest bidder. But in a surprise move, company executives suddenly canceled the auction and accepted a $26 billion leveraged buyout takeover offer from TPG Capital and the buyout arm of Goldman Sachs. Now, Wall Street investment bankers would own and control Alltel outright.

Within two years, Alltel’s independence would come to an end. In 2007, Alltel formally opened an auction to sell the company’s wireless assets to the highest bidder. But in a surprise move, company executives suddenly canceled the auction and accepted a $26 billion leveraged buyout takeover offer from TPG Capital and the buyout arm of Goldman Sachs. Now, Wall Street investment bankers would own and control Alltel outright.

Speculation in the financial press about why Alltel canceled the auction and didn’t even entertain other bidders for the company raised eyebrows at the time. The windfall payouts to Alltel’s executives disclosed in later Securities & Exchange Commission filings may have had something to do with it. Company executives won the equivalent of the Powerball Lotto:

- CEO Scott T. Ford received nearly $150 million dollars.

- Richard Massey, former chief strategy officer and general counsel walked away with almost $50 million.

- Alltel Chief Operating Officer Jeff Fox cleared more than $70 million.

- C.J. Duvall, who was EVP of human resources earned nearly $10 million.

- Kevin Beebe, group president of operations went home with more than $60 million.

That’s quite a haul for the top floor executives at Alltel heading for the exits.

That’s quite a haul for the top floor executives at Alltel heading for the exits.

But Goldman Sachs had no intention of running its own phone company for long. Analysts predicted the investment bank would hold onto Alltel for a year or two in hopes of selling it at a premium to one of the other wireless carriers, probably AT&T or Verizon.

That’s exactly what happened, except it only took seven months.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg In-Depth Look Goldman and TPG to Buy Alltel 5-21-07.flv[/flv]

Bloomberg News took an in-depth look at the 2007 Alltel acquisition by Goldman Sachs and ongoing wireless consolidation. (Corrected Video) (5 minutes)

Verizon Takes Over – The Dog & Pony Approval Circus

Verizon Takes Over – The Dog & Pony Approval Circus

With the collapse of the banking sector in 2007 and 2008, Goldman Sachs needed to get rid of assets to raise money. The subprime mortgage mess left banks with $386 billion in asset writedowns and credit losses. By putting Alltel up for sale, Goldman would earn $28.1 billion, enough to pay off the loans financing Alltel’s buyout months earlier, and even come out ahead.

The buyer, Verizon Wireless, sought to combine Alltel’s rural cell tower network with its own to expand coverage and pick up a stronger presence in middle America.

In the high stakes, high cost consolidation of telecommunications in the United States, what few regulatory hurdles Verizon would face getting the deal approved meant bringing forth the dog and pony show from Verizon’s lobbyists. The Federal Communications Commission could alter or even kill its deal. To make sure that didn’t happen, Verizon counted on the usual assortment of “dollar a holler” advocacy groups, heavy lobbying in Congress, and other friendly allies to help get the deal approved.

Unsurprisingly, Verizon can always count on help from free market allies and alleged community service groups with whom it has a financial relationship or contributes executive talent to serve on their boards. Most of these have no involvement in telecommunications matters, except when it interests or impacts Verizon. Suddenly they spring to action, conveniently submitting similar comments supporting whatever Verizon had on the agenda before the FCC.

[flv width=”640″ height=”500″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Little Rock Alltel-Verizon Merger Compilation 2008-2009.flv[/flv]

KLRT and KTHV-TV in Little Rock, Ark., where Alltel was headquartered, ran a series of reports explaining the impact the Verizon-Alltel merger would have on Alltel’s service and jobs in Little Rock. (23 minutes)

Selected Members of the Verizon Friendship Crew Filing Comments Supporting the Verizon Purchase of Alltel (click the names to read their letters to the FCC):

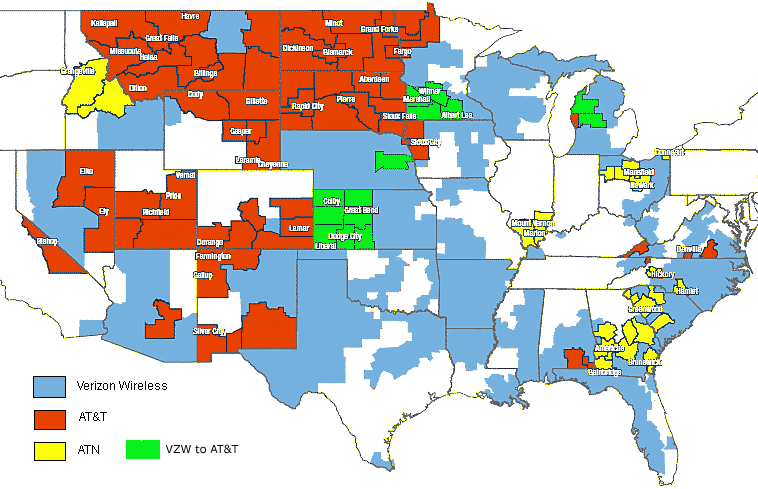

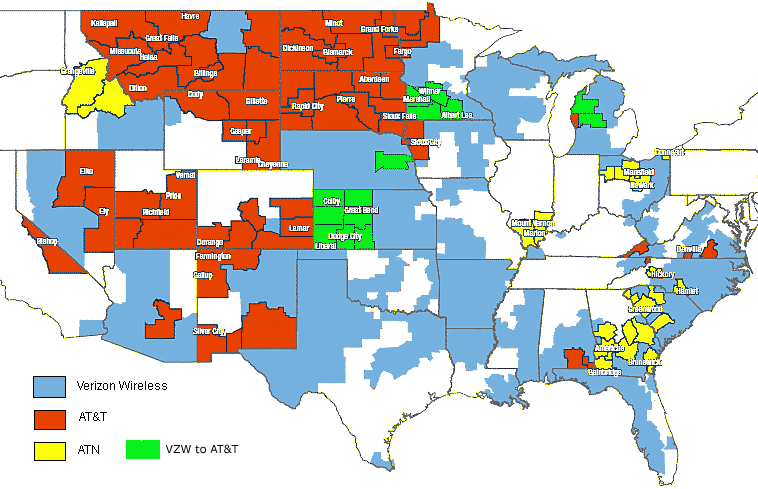

Alltel's service areas were carved up between three major providers - Verizon, AT&T, and ATN

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg Verizon Buying Alltel 6-5-08.flv[/flv]

Bloomberg News considered the business/industry implications of the Verizon-Alltel merger in these reports. (9 minutes)

Consumers Get Broken Promises & More Expensive Service

The benefits list of what Verizon promised to bring Alltel customers was heavily redacted in FCC filings as “highly confidential.” What was promised, in public, was that Verizon would deliver improved service to Alltel customers who could continue with their existing service plans..

The benefits list of what Verizon promised to bring Alltel customers was heavily redacted in FCC filings as “highly confidential.” What was promised, in public, was that Verizon would deliver improved service to Alltel customers who could continue with their existing service plans..

What consumers really got were major headaches, bad service, and much higher bills. Former Alltel customers continue to tear up Verizon Wireless’ support forums with page after page of complaints. As one former Alltel customer puts it, “we are the abandoned children of the redheaded stepchild.”

Some readers of Stop the Cap! shared their own experiences with the Alltel sale. Penny writes:

I first had Midwest Wireless that was bought out by Alltel which was just bought out by Verizon. With each switch I had to change my phone because something on the new system would not work on my old “previous provider” cell phone. Verizon has yet again said that for the “data charges” I can not block anything as my cell phone is too old and that I need to get a “Verizon” phone. My phone is not even a year old.

Enough about phones, data charges, rude customer service. You want to talk about dishonesty and unfair practices…just say Verizon.

In May I called and asked what I should do about leaving for a trip in which I would go out of my phone zone. The customer assistant that I talked to informed me that to avoid roaming charges I should temporarily switch to a national plan. I asked several times if I would be able to go back to my previous plan and was promised that I could set the start and end date for the new national plan. Well can you guess what they did? Yep they did the old bait and switch and from what I know about law….or what I thought about law was that this practice is illegal. Verizon started the new plan almost after I got back from my trip and plus would not set me back to my old plan. So now I had over 2 times the old bill plus roaming charges and less minutes. All I can say is my last call to Verizon was asking when my contract was up and what the termination fee is. By the way the $200 might be well spent.

Penny was switched away from her grandfathered Alltel plan to a new Verizon service plan, and potentially also ended up with a brand new two year contract, without new phones to accompany it. Any Verizon customer on a grandfathered service plan should never consider allowing a customer service representative to make substantial plan changes — you could lose your old plan. Grandfathered customers can make certain changes from the Verizon website (adding text plans, changing calling features on phones, etc.) without terminating their existing plan, but be cautious. Once you lose an old plan, you may never get it back.

Steve, another Stop the Cap! reader, writes:

I was with Alltel for 15 to 20 years and a very happy customer — never a problem. Then Verizon took over and it has been a problem ever since. First off let me tell you that we are truck drivers and travel all over the US. We were in Texas when our laptop died so we went and bought a new one. Our Alltel air card would not work in the new computer. This was at the time when Verizon was taking over, so we had to go to Verizon and get a new air card. By the way we had unlimited with Alltel. The sales person in Verizon sold us a new card and got us on the road again. From that day forward we have had to visit a Verizon store about our bill every month. Last month was the final straw. We did not like the 5 gig limit to begin with and did not trust it so we were watching it closely so we thought. When the MB’s got up near 4100 we called Verizon and they said you are no where near your 5 gig. Well when the bill came in it said we used over 8 gig and instead of our bill being 200.00 it was over 400.00 for the month . Since this has happened we have already dropped their phone service and may have to drop the Internet and pay the penalties.

Verizon's wireless modem

Steve ran into the problem former Alltel customers frequently encounter when traveling or moving outside of their old Alltel service area. Many Verizon representatives are not well trained about their new Alltel customers. Until the transition is complete, many Alltel customers still use equipment that gives priority to Alltel’s network first. If not correctly provisioned, equipment may not work properly outside of areas where Alltel had service.

[flv width=”640″ height=”500″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WTVT Tampa Verizon Alltel to refund charges 6-24-09.flv[/flv]

Alltel and Verizon were accused of bill cramming in the state of Florida — subjecting customers to monthly charges for “free” ringtones and other services. The Florida Attorney General’s office ordered refunds for all affected Floridians. Cell phone companies have an incentive to allow these services to get away with loading up customers’ bills with unauthorized charges — they receive a cut of the action. WTVT-TV in Tampa reports. (3 minutes)

Verizon’s 5GB usage cap also includes a steep overlimit penalty. We’ve seen reports that customers who use service around the country do not immediately see correct numbers for data usage. That can cause a sudden traffic spike as usage from other areas finally shows up on one’s account. Verizon customers should have the ability to opt-out from overlimit penalties. When their 5GB is used up, they should be presented with a screen that requires them to acknowledge they wish to continue using the service and face the consequences on their bill.

Verizon’s tricks and traps for Alltel customers always pay off for Verizon, almost never for customers:

- Verizon is doing everything possible to get Alltel customers to “upgrade” their service to Verizon plans so they can get them away from Alltel’s legacy plans offering more features for less money. Once a customer renews a contract with a new Verizon phone or makes a significant change to their service plan, they are switched to a new Verizon plan… often including tricks and traps. Unlimited texting costs extra on Verizon, as do many other features. Customers who mistakenly buy what they thought was a comparable service plan learn the errors of their ways when the $1,100 Verizon bill arrives a month later. Forgetting to add text and data plans can be an expensive mistake on Verizon’s network.

- Dangling a free or discounted phone upgrade for former Alltel customers often also requires an “upgraded” service plan… from Verizon. If you want a new subsidized phone, you may lose your old Alltel plan.

- In many areas, Alltel phones gravitate towards Alltel’s legacy cell network. That means the phone will choose a weaker cell tower formerly operated by Alltel instead of a closer Verizon cell site. A roaming/software upgrade normally would correct this and help route calls to the best possible cell site, but customers overwhelmingly complain that doesn’t happen with Alltel-provided phones. Customers are encouraged to choose a new Verizon phone instead… with a new Verizon service plan.

[flv width=”512″ height=”308″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WTKR Hampton Roads Norfolk NC man overcharged 400 dollars when switching from Alltel to Verizon 1-19-10.flv[/flv]

This former Alltel customer in North Carolina was charged $400 for an unjustified early termination fee when his service switched to Verizon Wireless as part of the merger. Despite repeated calls, Verizon-owned Alltel turned his account over to a collection agency. Verizon told him to pay off the Alltel collection agency account and they’d credit him $400. He paid and then Verizon refused to credit his account and turned him over to their collection agency who started calling him at work. They also ruined his credit. It took WTKR-TV in Hampton Roads, Virginia airing this story on the 6 o’clock news to get Verizon’s attention after seven months. (2 minutes)

Things are even more complicated in areas where the FCC has forced Alltel to divest its wireless assets and not transfer them to Verizon. In most areas, those customers will shortly discover they are becoming part of AT&T’s wireless family, as AT&T bought the majority of those divested markets. AT&T, however, does not operate with the same wireless standard Alltel and Verizon do. AT&T phones work on the GSM standard while Alltel and Verizon work on CDMA. For the time being, AT&T will simply operate the existing CDMA network Alltel used to own, but eventually every affected customer will get a free upgrade to a new GSM phone. That upgrade better come quick for frequent travelers who are former Alltel customers switched to AT&T. They’ll find getting service from AT&T outside of their home areas difficult on a network that uses an entirely different standard. AT&T will likely have to maintain roaming agreements with Verizon for former Alltel customers until conversion is complete.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/South Dakota Alltel ATT 6-24-10.flv[/flv]

KELO and KSFY-TV, both in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, informed South Dakota’s former Alltel customers they’d soon have AT&T as their cell phone company, making Apple’s iPod available in stores in the state for the first time. (3 minutes)

A handful of customers won’t end up with either Verizon or AT&T. In parts of Wisconsin, Element Mobile will take control of their Alltel account. But nearly a million customers will find their former Alltel service is now provided by… Alltel?

The Return of Alltel Wireless

McGill

Allied Wireless Communications Corp., which is staffed by former Alltel employees, has acquired the remaining leftover pieces of Alltel’s network, including its name, for $223 million dollars. The all-new Alltel will have the same logo and calling plan features the old Alltel offered, and for 900,000 customers, it will be as if they never left.

“We feel like it’s putting the bank back together here in Little Rock,” Wade McGill, chief administrative officer for Alltel Wireless and AWCC told RCR Wireless. The original Alltel Corp. was headquartered in Little Rock, Ark., before being acquired by Verizon Wireless for $28 billion in early 2009. As part of the acquisition, Verizon Wireless was forced to divest some markets, a majority of which were acquired by AT&T Mobility for $3 billion, with most of the rest picked up by what will remain Alltel.

The company will have extensive roaming agreements for nationwide coverage and will focus on maintaining high quality customer care.

“The ability to retain the brand was key in these markets and you can’t underestimate the value of that,” McGill noted, adding that more than 50% of its current customer base have been Alltel customers for more than six years.

“We need to have a laser focus on the customer experience and being local,” McGill explained, citing a common mantra of rural carriers forced to compete against large, nationwide operators. “That’s how we want to think about our plans moving forward. … I think our plan is to grow organically at first and just focus on providing excellent customer service and support.”

But that doesn’t preclude Alltel from starting to expand operations to other parts of the country, perhaps even in areas now taken over by Verizon.

The new Alltel will remain a CDMA provider with plans to move to the LTE standard, which will deliver a 4G-like experience.

Going Back to the Future

In the end, many of the 13 million former Alltel customers probably wish they could have their old Alltel back, too.

Instead, they got wheeled and dealed away, first by an investment bank/casino that later used taxpayer dollars to bail itself out of its own greed, then by Verizon and AT&T who promise a future of higher bills and poorer service for many trapped in two year contracts. Too often, what’s in the best interests of consumers are an afterthought in these kinds of transactions, even today. Despite the FCC’s own findings that wireless competition is shrinking in a consolidating wireless world, they still found a way to green light deals like this that reduce competition even further.

Consolidation of the wireless industry into two or three mega-carriers is a dream come true… if you are one of those carriers (or Wall Street). But for everyone else, it’s a competition wasteland, where innovation and disruptive marketing wane into comfortable and predictable businesses where participants learn not to rock the boat. If they did, a lot of their accumulated money could fall overboard.

Consolidation of the wireless industry into two or three mega-carriers is a dream come true… if you are one of those carriers (or Wall Street). But for everyone else, it’s a competition wasteland, where innovation and disruptive marketing wane into comfortable and predictable businesses where participants learn not to rock the boat. If they did, a lot of their accumulated money could fall overboard.

Subscribe

Subscribe