The Rochester, Minn. Amateur Radio Club spent months documenting potential interference from another problem technology: Broadband Over Power Lines.

Back in 2004, the Federal Communications Commission was looking for ways to expand broadband competition. Borrowing from a mild success story in Europe, the Washington regulator, with the help of a well-financed lobbying campaign, approved new technology that would deliver broadband service over power lines, known as BPL. The promises were great — fast access over an extensive, already-wired network that reached virtually every home in the country. Glossy brochures promising a new generation of broadband and new competition were sent to every member of Congress. Dollar-a-holler groups like the New Millennium Research Council produced “research reports” claiming the technology would advent a broadband revolution. Some investors used to sleepy returns from utility companies dreamed about the promise of a rich new revenue stream pitching broadband service.

But there was a slight problem. The technology worked better on paper than it did in real life. Even more importantly, it carried more baggage than USAir. Delivering wideband broadband signals over unshielded power cables never designed to carry radio frequencies meant interference — a lot of it, to any radio band the broadband signal occupied. That meant a horrible listening experience on AM, and practically no listening at all over the shortwave bands, designated for military communications, international broadcasters, and the amateur radio community.

The FCC approved and supported the technology anyway, promising filters and other mitigation for those impacted by interference — a notion scoffed at by the American Radio Relay League, a group representing amateur radio operators.

So why don’t we have that third choice for broadband today? BPL technology buried itself as its woeful performance could never match the high-flying marketing promises found in the brochure.

Fast forward to 2011 and manufacturers of satellite navigation devices, popularly known as GPS units, are terrified America is about to embark on another dreadful mistake.

LightSquared, a new entrant in the telecommunications marketplace, is constructing a nationwide 4G wireless broadband network with traditional ground-based antenna towers supplemented with a satellite system providing coverage in rural areas. The company’s new network will occupy a frequency band just adjacent to that used by global positioning satellites, the backbone of the GPS system that some LightSquared critics contend will be crippled if the company’s 4G network is ever switched on.

[flv width=”640″ height=”388″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/LightSquared Intro.flv[/flv]

LightSquared released this promotional video talking up their future network. (2 minutes)

Early interference tests conducted by a federal working group show those critics may be right. Because satellite signals are so weak, manufacturers like Tom-Tom and Garmin must create highly sensitive GPS receivers to handle the faint signals. Because these units are not always selective enough to reject adjacent signal interference, a neighboring transmitter delivering a much more powerful signal — such as that from LightSquared — could overwhelm them.

Early interference tests conducted by a federal working group show those critics may be right. Because satellite signals are so weak, manufacturers like Tom-Tom and Garmin must create highly sensitive GPS receivers to handle the faint signals. Because these units are not always selective enough to reject adjacent signal interference, a neighboring transmitter delivering a much more powerful signal — such as that from LightSquared — could overwhelm them.

Independent testing found serious interference problems even for professional grade GPS units used by civil aviation, ships, and emergency responders. A sampling:

- GM’s OnStar system received significant interference, making it difficult to identify the location of crashed vehicles and disrupting turn-by-turn directions and other navigation services;

- In recent tests in New Mexico, LightSquared caused GPS receivers used by nearby police, fire and ambulance crews to lose reception;

- John Deere’s agricultural equipment incorporating GPS technology failed to receive signals during the LightSquared testing;

- Both the Coast Guard and NASA reported significant interference to their GPS receivers;

- The Federal Aviation Administration reports their GPS receivers completely failed while the tests were conducted.

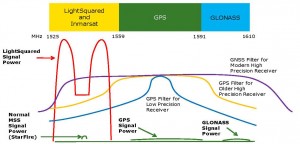

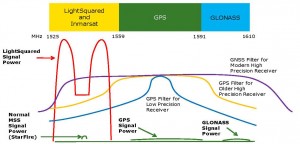

The red box identifies the spectrum assigned to LightSquared. Its immediate neighbors are faint signals from communications satellites. (click to enlarge)

With complaints like that coming after a small-scale test, the thought of 40,000 ground-based LightSquared towers obliterating the nation’s access to GPS is more than just a little concerning to users and manufacturers.

“LightSquared’s network could cause devastating interference to all different kinds of GPS receivers,” Jim Kirkland, vice president and general counsel of Trimble Navigation Ltd., told the Washington Post. Trimble manufactures GPS devices.

The Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics advised the FAA its own independent tests of the LightSquared system found the consequences of turning this 4G wireless service on would be cataclysmic for GPS signals, making most satellite navigation equipment completely useless in most major metropolitan areas.

LightSquared executive vice president Jeffrey Carlisle told the Post he remained confident that the two systems could co-exist, even admitting he expected to find interference issues. Carlisle says the real question is how to mitigate it.

This is not the first time interference issues have come before the FCC. Nearby spectrum neighbors often don’t get along, especially when one licensed user relies on weak signals from space and the other utilizes more powerful ground-based transmitters. The Commission has even fielded complaints over garage door openers interfering with certain military radios.

LightSquared’s network concept isn’t by itself the problem. XM Radio manages to operate its mix of satellite-delivered radio and 900 ground-based repeater transmitters without creating interference for other users.

Deere Companies produced this diagram showing a comparison of the respective power levels of LightSquared signals vs. satellite navigation signals.

Unfortunately for LightSquared, it has several problems to contend with, the most significant being its “zoning problem.” The souped-up 4G network is simply not in character for the spectrum neighborhood it calls home. It’s a McMansion being built in a neighborhood of cottages. LightSquared’s neighbors are low powered satellite signals in the 1-2Ghz range, including those from the satellites which provide GPS. In certain cases, receiver equipment can be designed to reject the adjacent interference a network like LightSquared could create, but with millions of existing GPS units already in use, that may prove impractical.

LightSquared has tried to rope off its channel space as much as possible, trading spectrum with other nearby users to create a nearly contiguous 20Mhz slice it can dedicate to its signals, in hopes of reducing interference. But the recent tests suggest this may not be enough. General Motors suggested LightSquared needs to find a better neighborhood — one more suited to the kind of signal it wants to offer. That could come from a spectrum trade or a frequency reallocation by the FCC.

The FCC is taking a “wait and see” approach so far, claiming further tests are needed. But the agency earlier pledged it would not allow LightSquared to operate its network if it created major interference problems for other spectrum users. Some GPS manufacturers think that commitment is too vague, because “major interference” is in the eye of the beholder.

Those concerns may be warranted, considering the FCC earlier found its way clear to ignore the documented interference Broadband Over Power Lines created over both the AM and shortwave radio dial. Even after a blizzard of lobbying and campaign contributions won support for BPL in Washington, the ultimately inferior product that resulted couldn’t win the support of the group that ultimately mattered most — paying customers.

[flv width=”640″ height=”500″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg Ahuja Says LightSquared to Finish 4G Network Before 2016 6-11-11.flv[/flv]

Sanjiv Ahuja, chief executive officer of LightSquared, talks about the company’s efforts to build a wireless broadband network as other spectrum users challenge the company’s potential to create interference. (7 minutes)

LightSquared, feeling pressure after independent studies showed significant interference problems created by its wireless broadband network, suddenly announced a “solution” to the problem — one getting skeptical reviews from those critical of the project.

LightSquared, feeling pressure after independent studies showed significant interference problems created by its wireless broadband network, suddenly announced a “solution” to the problem — one getting skeptical reviews from those critical of the project.

Subscribe

Subscribe