Property owners in New Zealand may have to trim back or remove trees if they are proven to interfere with Wi-Fi or wireless broadband services in the neighborhood, according to an interesting High Court judgment that could establish a wide-ranging precedent.

Property owners in New Zealand may have to trim back or remove trees if they are proven to interfere with Wi-Fi or wireless broadband services in the neighborhood, according to an interesting High Court judgment that could establish a wide-ranging precedent.

As short-range 5G wireless internet services become established, high frequency and millimeter wave-based signals depend on line-of-sight communications with end users. Trees and buildings can reduce signal range or block the signal entirely, rendering the service unusable. In this case, an appeals judge was asked to rule whether broadband users or property owners took precedence when a large stand of trees or a building in an adjacent yard made wireless reception more difficult or impossible.

Justice Sally Fitzgerald found that when alternative solutions like relocating a receiver cannot be found to mitigate reception problems, nearby property owners may have to take steps to protect neighbors’ access to Wi-Fi and other wireless services, under a new interpretation of Section 335(1)(vi) of the [Property Law] Act of New Zealand. Similar laws are in place in North America and European countries.

The decision could result in a dramatic increase in legal challenges from frustrated neighbors who cannot get good reception because adjacent property owners prefer a tree-filled landscape.

Justice Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald based her decision on basic property laws that make illegal anything that can unduly interfere with the reasonable use and enjoyment of private property. Such laws are used as a basis for noise ordinances, zoning restrictions, restrictions on commercial use of residential property, and placement of structures on or near property lines. This judge found no special distinction between physical objects or noise and wireless transmissions. But she did find reasonable limitations on what would constitute a valid complaint.

In this case, Ian and Karen Vickery brought the complaint against their neighbor Christine Thoroughgood, for interfering with their access to wireless internet by refusing to trim the trees on her property line. But the judge found a better answer than ordering a robust tree trimming. Fitzgerald found the Vickery’s already receive a suitable signal after placing a receiver on a pole located away from their home. Therefore, the judge ruled against the complaint by the Kiapara Flats couple, even though they preferred placing the receiver on their home.

Legal observers found the case precedent-setting, despite its low-key outcome, because this High Court judge has established a right of access to broadband that takes precedence over property owners’ landscaping and buildings. Under certain circumstances, a neighbor may be forced to trim, remove, or alter trees and structures on their land if a neighbor can prove it directly interferes with their right to access wireless signals like broadband in a way that cannot be mitigated.

From the decision:

I am satisfied, and Mr. Allan properly accepted, that undue interference with a Wi-Fi signal caused by trees could constitute an undue interference with the reasonable use and enjoyment of an applicant’s land for the purposes of s 335(1)(vi) of the Act.

From reviewing the evidence, however, I do not agree that the Judge erred in accepting independent expert evidence (in fact called by Mr. Vickery) which objectively contradicted Mr. Vickery’s personal evidence on the issue as to Wi-Fi signal.

The expert, Mr. Lancaster, explained that Mr. Vickery’s Wi-Fi service is a “fixed wireless solution”. He notes in his technical report that it works by having the internet service provider establishing a “broadcast site” in a prominent location and connecting to customers with clear “line of sight” to that broadcast site.

In this case, the broadcast site (provided by Compass Wireless) is located on Moirs Hill Road. Mr. Lancaster notes that “nominally the solution will service customers up to 30 kilometres away from the broadcast site subject to a clear unobstructed line of sight.” In this way, Mr. Lancaster confirms that trees could obstruct the otherwise clear line of sight.

At present, the Wi-Fi transponder (or receiver) at the Vickerys’ home is mounted on a pole a little distance away from the rear of the house. I viewed its location during my site visit and have reviewed the photographs in Mr. Lancaster’s report. With the transponder located in its present position (referred to by Mr. Lancaster as “Location A”), Mr. Lancaster states:

There is currently a clear signal to the installed dish and other parts of the property, the signal has remained good for the past two years since installation.

This current location, however, is not Mr. Vickery’s preferred location. He notes that the present location is in a particularly windy site and on one occasion the wind was so strong it blew the cable out of the back of the aerial. Mr. Vickery also noted that another much larger stand of pine trees on the Thoroughgoods’ land, some considerable distance away, are also impacting what is referred to as the “Fresnel zone” of the Wi-Fi connection in its present location.

Mr. Vickery’s preferred location is closer to and attached to the back of the house itself, where it would be easier for Mr. Vickery to service the transponder. At this location however, Mr. Vickery says the trees in issue will interfere with the signal.

Mr. Lancaster states in his report that he spent over two hours on site and only identified two other locations (other than the present location, Location A) which he would consider appropriate for an installation.

The first of these alternative locations (Location B) is on the northeast corner wall of the home — Mr. Vickery’s preferred location. Mr. Lancaster states “this is the location the Compass installers would have chosen by default and as a standard installation”. In relation to Location B, Mr. Lancaster states “it is obviously at risk due to close proximity to the existing tree/shrub planted boundary, being approximately three metres above ground level.” He states that to retain adequate signal at this location, a window would be required in the shelter belt hedge — the trees in issue in this case.

In light of the independent expert evidence, I do not accept the Judge erred in concluding there was no undue interference with the Vickerys’ Wi-Fi signal. It is important to reiterate that not only does the expert evidence not indicate an interference, but the standard required by the legislation is an “undue” interference in any event. The expert evidence confirms this threshold has not been met.

Accordingly, while it is true that Mr. Vickery’s preferred location for the Wi-Fi transponder would be on the wall of the home, there is clearly an alternative location which is currently being used and which is considered by Mr. Lancaster to be adequate. There is also a further alternative and adequate location (Location C). And although this location would require cabling, this would not in my view be unreasonable in the circumstances.

I accordingly do not consider the ground of appeal concerning Wi-Fi has been made out.

Subscribe

Subscribe The Federal Communications Commission is pushing hard to free up additional spectrum in some unlikely extremely high frequency ranges — some at 95 GHz or higher, for the next generation of wireless services.

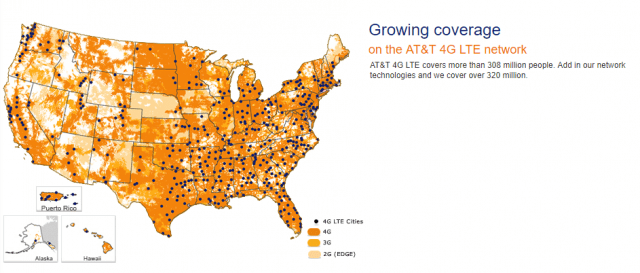

The Federal Communications Commission is pushing hard to free up additional spectrum in some unlikely extremely high frequency ranges — some at 95 GHz or higher, for the next generation of wireless services. There are proposals and counter proposals from the satellite industry and wireless companies over how to manage sharing this band. Most are coalescing around the idea of sequestering 100 MHz of spectrum at the low-end of the band and using 3700-3800 MHz for high-speed wireless broadband. Some want satellite operators to clear out of this section of frequencies voluntarily, others propose compensation similar to what was given to television stations to relocate their channel positions. Google is pushing for a plan that would offer mobile 5G service in large urban areas and 25 Mbps – 1 Gbps fixed wireless broadband in rural and residential areas.

There are proposals and counter proposals from the satellite industry and wireless companies over how to manage sharing this band. Most are coalescing around the idea of sequestering 100 MHz of spectrum at the low-end of the band and using 3700-3800 MHz for high-speed wireless broadband. Some want satellite operators to clear out of this section of frequencies voluntarily, others propose compensation similar to what was given to television stations to relocate their channel positions. Google is pushing for a plan that would offer mobile 5G service in large urban areas and 25 Mbps – 1 Gbps fixed wireless broadband in rural and residential areas. Many agencies contemplating use of this band discovered equipment that supported 4.9 GHz was hard to find and extremely expensive. Most public safety agencies seeking grants or other funding to improve their communications equipment opted to transition to digital P25 networks that operate on much lower frequencies and use equipment that is now widely available and, in comparison, much cheaper. Many agencies are conservative about using new technology as well, concerned a communications failure could cost the life of a fire or police responder. As a result, of the 90,000 organizations certified for licenses in this band, only 3,174 have been granted. That represents a take rate of just 3.5%. The band, as one might expect, is effectively dead in most areas, underutilized in others.

Many agencies contemplating use of this band discovered equipment that supported 4.9 GHz was hard to find and extremely expensive. Most public safety agencies seeking grants or other funding to improve their communications equipment opted to transition to digital P25 networks that operate on much lower frequencies and use equipment that is now widely available and, in comparison, much cheaper. Many agencies are conservative about using new technology as well, concerned a communications failure could cost the life of a fire or police responder. As a result, of the 90,000 organizations certified for licenses in this band, only 3,174 have been granted. That represents a take rate of just 3.5%. The band, as one might expect, is effectively dead in most areas, underutilized in others. Although the 28 GHz band has many licensed users already, the 24 GHz band does not, and the wireless industry is interested in grabbing vast swaths of spectrum in this band for 5G home broadband. Known as “millimeter wave spectrum,” these two bands are expected to be a big part of the 5G fixed wireless services being planned by some carriers. Verizon acquired Straight Path late in 2017, which had collected a large number of licenses for this frequency range. Today, Verizon holds almost 30% of all currently licensed millimeter wave spectrum, an untenable situation if you are AT&T, T-Mobile, or Sprint. T-Mobile has been the most aggressive seeking more spectrum to compete with Verizon in this frequency range, and has purchased almost 1,150 MHz covering Ohio for use with a 5G project the company is working on.

Although the 28 GHz band has many licensed users already, the 24 GHz band does not, and the wireless industry is interested in grabbing vast swaths of spectrum in this band for 5G home broadband. Known as “millimeter wave spectrum,” these two bands are expected to be a big part of the 5G fixed wireless services being planned by some carriers. Verizon acquired Straight Path late in 2017, which had collected a large number of licenses for this frequency range. Today, Verizon holds almost 30% of all currently licensed millimeter wave spectrum, an untenable situation if you are AT&T, T-Mobile, or Sprint. T-Mobile has been the most aggressive seeking more spectrum to compete with Verizon in this frequency range, and has purchased almost 1,150 MHz covering Ohio for use with a 5G project the company is working on.

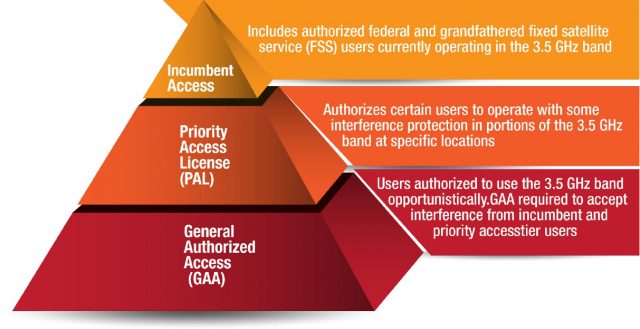

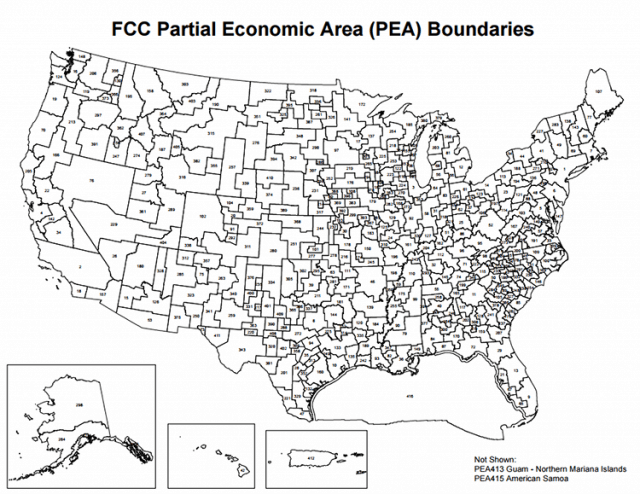

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Verizon will invite several thousand customers in 11 cities to participate in a “pre-commercial”

Verizon will invite several thousand customers in 11 cities to participate in a “pre-commercial”