Our friends at Fierce Cable put together a list of the top-paid telecommunications executives, and they’re in the money. Your money. While your rates keep going up, their take-home pay often is, too.

Remarkably, actual performance as executives (or lack, thereof) often had no relationship to their ultimate pay package, with a handful of exceptions:

Cable & Satellite

Brian L. Roberts, Comcast — $26.9 million: The Roberts family has dominated Comcast since the 1980s, so it is no surprise their pay packages are as colossal as the company itself.

Michael J. Lovett, Charter Communications — $20.54 million: He resigned in Feb. 2012 but got a great golden parachute: nearly double the compensation he earned the year before. Charter is one of America’s least-distinguished cable companies, usually scoring just above “pond scum” in popularity with customers. But you can take that trash talk when you walk $20 million to the bank.

Glenn A. Britt, Time Warner Cable — $16.43 million: His pay went down slightly (well, by a million dollars but with that kind of money, does it really matter?) in 2011. Britt has been around at some iteration of Time since 1972… when Nixon was still president, so he worked his way to the top. But some of his best accomplishments are irritating his customers with talk of overcharging them for Internet access.

James L. Dolan, Cablevision — $11.45 million: The Dolan family and Cablevision go together like cookies and milk, but Wall Street can’t help but bet when the family will finally cash out of cable and sell the company to Time Warner or Comcast. With $11 million in salary, stock awards, and bonuses, what’s the hurry?

Joseph Clayton, Dish Network — $9.84 million: Clayton is a Dish freshman, only coming on board 11 months ago. His salary was a paltry $467,000 in 2011. Thank goodness for the $9 mil in stock and bonus pay!

Michael D. White, DirecTV — $5.94 million: Ouch… a pay cut. White made $32.93 million the year before. Now he’ll have to clip coupons from the Sunday newspaper like the rest of us.

Rodger L. Johnson, Knology — $3.13 million: Not bad for running a company almost nobody has heard of and will soon no longer exist. WideOpenWest bought them out last month.

The Wireline Companies & Their Friends

Stephenson: Blew a $39 billion dollar merger deal with T-Mobile, but walks away with $22 million in pay anyway.

Lowell McAdam, Verizon — $23.1 million: McAdam’s promotion paid handsomely. As former chief operating officer, he only walked home with a little more than $7 million last year. Now he’s earning every penny conjuring up ways he can do away with your cell phone subsidy -and- keep Verizon Wireless’ rates as high as ever.

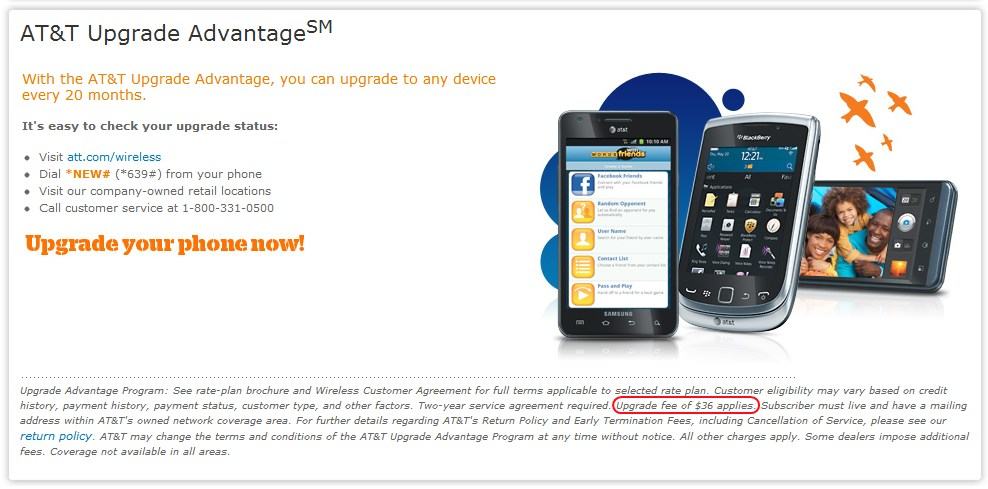

Randall Stephenson, AT&T — $22.01 million: If you blew a multi-billion dollar merger deal at your company, do you think the only punishment you’d receive is a $5 million pay cut? Stephenson is the cat that fell out of the wireless merger window, and landed on his feet unharmed. Unfortunately the same isn’t true for his customers.

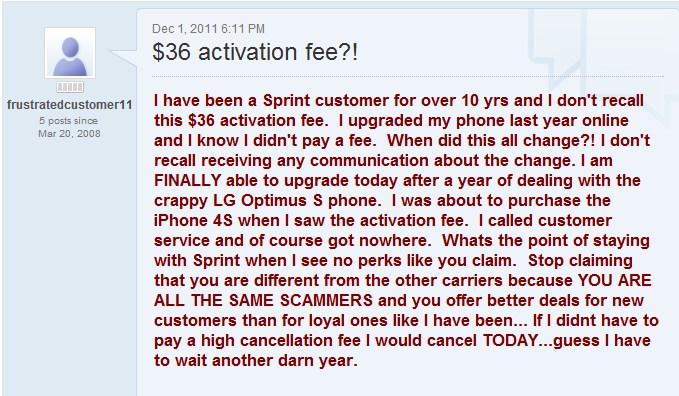

Dan Hesse, Sprint — $11.88 million: His pay is down about $2 million from 2010, and he recently announced he was going to take another pay cut for the team. If anyone deserves hazard pay, Hesse is the man. Wall Street hates him for not following his competitors gouging customers with higher prices and more restrictive service plans and policies. The big money crowd in New York’s financial district already has his going away party well-planned.

Jeff Gardner, Windstream — $9.78 million: His pay is up around $2 million. Windstream can afford it, acquiring companies later stripped clean of employees. PAETEC workers will learn this lesson soon enough. At Windstream, all the money rises to the top… management that is.

George A. Cope, Bell Canada — $9.6 million: His salary more than doubled over 2010 and why not. Bell is the first telecommunications company in North America to be audacious enough to demand an entire country be stripped of flat rate Internet service. That move managed to organize 500,000 Canadians that normally are resigned to the fact the revolving door at the Canadian Radio-tv and Telecommunications Commission has locked them out for years. Thanks Bell!

Glen F. Post III, CenturyLink — $8.55 million: Post saw his pay slashed from $14.5 million the year before, but merger deals like Qwest (with the corresponding huge bonus for pulling it off) only come once or twice in a career.

Maggie Wilderotter, Frontier — $6.72 million: No, we don’t understand it either. Her pay is down from $8.58 million, but considering Frontier’s current stock price and bottom-rated service, wouldn’t half of this money be better spent on improving broadband in states like West Virginia?

John F. Cassidy, Cincinnati Bell — $6.06 million: Cassidy earned more than two million more the year before. Cincinnati Bell is an aberration in an industry that is convinced the only good thing telecom companies can do is merge with each other to get bigger and bigger.

Paul H. Sunu, FairPoint — $4.25 million: The company that couldn’t find one customer’s business on a service call despite being literally right next door to FairPoint itself, is clawing its way back from bankruptcy and Sunu’s pay package reflects that. He only earned $775,000 the year earlier.

Ian Paul Livingston, BT — $3.8 million: British Telecom’s chief got a modest salary hike in 2011, and the U.K. phone company has done modestly better recognizing better broadband in the key to its future. BT is the AT&T of the United Kingdom, but British salaries are downright frugal compared to the high flyers on this side of the Atlantic.

David A. Wittwer, TDS Telecom — $2.29 million: You can’t complain about a cool $2 million in salary for a company with only around 1.1 million customers.

Ben Verwaayen, Alcatel-Lucent — $2.25 million: His salary dropped slightly from 2010. Alcatel-Lucent could do considerably better if they can win the public policy debate that fiber optic broadband is the wave of the future. Alcatel-Lucent is a major player.

Subscribe

Subscribe