It wasn’t difficult to understand Verizon’s sudden reticence about continuing its fiber to the home expansion program begun under the leadership of its former chairman and CEO Ivan Seidenberg. Starting his career with Verizon predecessor New York Telephone as a cable splicer, he worked his way to the top. Seidenberg understood Verizon’s wireline future as a landline phone provider was limited at best. With his approval, Verizon began retiring decades-old copper wiring and replaced it with fiber optics, primarily in the company’s biggest service areas and most affluent suburbs along the east coast. The service was dubbed FiOS, and it has consistently won high marks from customers and consumer groups.

It wasn’t difficult to understand Verizon’s sudden reticence about continuing its fiber to the home expansion program begun under the leadership of its former chairman and CEO Ivan Seidenberg. Starting his career with Verizon predecessor New York Telephone as a cable splicer, he worked his way to the top. Seidenberg understood Verizon’s wireline future as a landline phone provider was limited at best. With his approval, Verizon began retiring decades-old copper wiring and replaced it with fiber optics, primarily in the company’s biggest service areas and most affluent suburbs along the east coast. The service was dubbed FiOS, and it has consistently won high marks from customers and consumer groups.

Seidenberg

Seidenberg hoped by offering customers television, phone, and internet access, they would have a reason to stay with the phone company. Verizon’s choice of installing fiber right up the side of customer homes proved highly controversial on Wall Street. Seidenberg argued that reduced maintenance expenses and the ability to outperform their cable competitors made fiber the right choice, but many Wall Street analysts complained Verizon was spending too much on upgrades with no evidence it would cause a rush of returning customers. By early 2010, Verizon’s overall weak financial performance coupled with Wall Street’s chorus of criticism that Verizon was overspending to acquire new customers, forced Seidenberg to put further FiOS expansion on hold. Verizon committed to complete its existing commitments to expand FiOS, but with the exception of a handful of special cases, stopped further expansion into new areas until this past spring, when the company suddenly announced it would expand FiOS into the city of Boston.

Seidenberg stepped down as CEO in July 2011 and was replaced by Lowell McAdam. McAdam spent five years as CEO and chief operating officer of Verizon Wireless and had been involved in the wireless industry for many years prior to that. It has not surprised anyone that McAdam’s focus has remained on Verizon’s wireless business.

McAdam has never been a booster of FiOS as a copper wireline replacement. Verizon’s investments under McAdam have primarily benefited its wireless operations, which enjoy high average revenue per customer and a healthy profit margin. Over the last six years of FiOS expansion stagnation, Verizon’s legacy copper wireline business has continued to experience massive customer losses. Revenue from FiOS has been much stronger, yet Verizon’s management remained reticent about spending billions to restart fiber expansion. In fact, Verizon’s wireline network (including FiOS) continues to shrink as Verizon sells off parts of its service area to independent phone companies, predominately Frontier Communications. Many analysts expect this trend to continue, and some suspect Verizon could eventually abandon the wireline business altogether and become a wireless-only company.

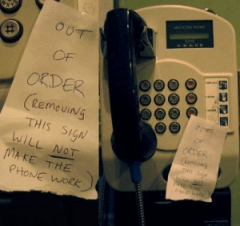

With little interest in maintaining or upgrading its wired networks, customers stuck in FiOS-less communities complain Verizon’s service has been deteriorating. As long as McAdam remains at the head of Verizon, it seemed likely customers stuck with one option – Verizon DSL – would be trapped with slow speed internet access indefinitely.

Verizon’s FiOS expansion rises from the dead?

But McAdam has finally shown some excitement for a high-speed internet service he does seem willing to back. Verizon’s ongoing trials of 5G wireless service, if successful, could spark a major expansion of Verizon Wireless into the fixed wireless broadband business. Unlike earlier wireless data technologies, 5G is likely to be an extremely short-range wireless standard that will depend on a massive deployment of “small cells” that can deliver gigabit plus broadband speeds across a range of around 1,500 feet in the most ideal conditions. That’s better than Wi-Fi but a lot less than the range of traditional cell towers offering 4G service.

What particularly interests McAdam is the fact the cost of deploying 5G networks could be dramatically less than digging up neighborhoods to install fiber. Verizon’s marketing mavens have already taken to calling 5G “wireless fiber.”

“I think of 5G initially as wireless technology that can provide an enhanced broadband experience that could only previously be delivered with physical fiber to the customer,” said McAdam during Verizon’s second-quarter earnings call. “With wireless fiber the so-called last mile can be a virtual connection, dramatically changing our cost structure.”

McAdam

Verizon’s engineers claim they can build 5G networking into existing 4G “small cells” that are already being deployed today as part of Verizon’s efforts to increase the density of its cellular network and share the increasing data demands being placed on its network. In fact, McAdam admitted Verizon’s near-future would not depend on acquiring a lot of new wireless spectrum. Instead, it will expand its network of cell towers and small cells to cut the number of customers trying to share the same wireless bandwidth.

McAdam’s 5G plan depends on using extremely high frequency millimeter wave spectrum, which can only travel line-of-sight. Buildings block the signal and thick foliage on trees can dramatically cut its effective range. That means a new housing development of 200 homes with few trees to get in the way could probably be served with small cells, if mounted high enough above the ground to avoid obstructions. But an older neighborhood with decades-old trees with a significant canopy could make reception much more difficult and require more small cells. Another potential downside: just like Wi-Fi in a busy mall or restaurant, 5G service will be shared among all subscribers within range of the signal. That could involve an entire neighborhood, potentially reducing speed and performance during peak usage times.

Verizon won’t know how well the service will perform in the real world until it can launch service trials, likely to come in 2017. But Verizon has also made it clear it wants to be a major, if not dominant player in the 5G marketplace, so plenty of money to construct 5G networks will likely be available if tests go well.

Ironically, to make 5G service possible, Verizon will need to replace a lot of its existing copper network it has consistently refused to upgrade with the same fiber optic cables that make FiOS possible. It needs the fiber infrastructure to connect the large number of small cells that would have to be installed throughout cities and suburbs. That may be the driving force behind Verizon’s sudden resumed interest in restarting FiOS expansion this year, beginning in Boston.

“We will create a single fiber optic network platform capable of supporting wireless and wireline technologies and multiple products,” McAdam told investors. “In particular, we believe the fiber deployment will create economic growth for Boston. And we are talking to other cities about similar partnerships. No longer are discussions solely about local franchise rights, but how to make forward-looking cities more productive and effective.”

If McAdam can convince investors fiber expansion is right for them, the company can also bring traditional FiOS to neighborhoods where demand warrants or wait until 5G becomes a commercially available product and offer that instead. Or both.

There are a lot of unanswered questions about how Verizon will ultimately market 5G. The company could adopt its wireless philosophy of not offering customers unlimited use service, and charge premium prices for fast speeds tied to a 5G data plan. Or it could market the service exactly the same as it sells essentially unlimited FiOS. Customer reaction will likely depend on usage caps, pricing, and performance. As a shared technology, if speeds lag on Verizon’s 5G network as a result of customer demand, it will prove a poor substitute to FiOS.

Verizon has left an undetermined number of its landline customers in the Tribeca neighborhood of New York City without phone or DSL service since Aug. 4 and has no plans to restore it before Aug. 22.

Verizon has left an undetermined number of its landline customers in the Tribeca neighborhood of New York City without phone or DSL service since Aug. 4 and has no plans to restore it before Aug. 22.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Two years after Verizon promised its FiOS fiber to the home service would be available to every resident of New York City, the city sued Verizon Communications on Monday, alleging Verizon failed to meet its commitment.

Two years after Verizon promised its FiOS fiber to the home service would be available to every resident of New York City, the city sued Verizon Communications on Monday, alleging Verizon failed to meet its commitment.

It wasn’t difficult to understand Verizon’s sudden reticence about continuing its fiber to the home expansion program begun under the leadership of its former chairman and CEO Ivan Seidenberg. Starting his career with Verizon predecessor New York Telephone as a cable splicer, he worked his way to the top. Seidenberg understood Verizon’s wireline future as a landline phone provider was limited at best. With his approval, Verizon began retiring decades-old copper wiring and replaced it with fiber optics, primarily in the company’s biggest service areas and most affluent suburbs along the east coast. The service was dubbed FiOS, and it has consistently won high marks from customers and consumer groups.

It wasn’t difficult to understand Verizon’s sudden reticence about continuing its fiber to the home expansion program begun under the leadership of its former chairman and CEO Ivan Seidenberg. Starting his career with Verizon predecessor New York Telephone as a cable splicer, he worked his way to the top. Seidenberg understood Verizon’s wireline future as a landline phone provider was limited at best. With his approval, Verizon began retiring decades-old copper wiring and replaced it with fiber optics, primarily in the company’s biggest service areas and most affluent suburbs along the east coast. The service was dubbed FiOS, and it has consistently won high marks from customers and consumer groups.