A word to the wise: using public money to build a middle mile broadband network without any customers lined up to sign up is a disaster waiting to happen.

A word to the wise: using public money to build a middle mile broadband network without any customers lined up to sign up is a disaster waiting to happen.

In April, the disaster arrived in the form of a Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing on behalf of the Florida Rural Broadband Alliance (FRBA), which threw away $24 million in federal grants on a network that was so unviable, the contractor that was supposed to run it apparently ran away instead, resulting in confusion and an eventual declaration it was “doomed to fail” anyway.

The sordid story started almost seven years ago when Florida’s Heartland Regional Economic Development Initiative (FHREDI) and Opportunity Florida (OF) — two non-profit organizations dedicated to spurring economic development across rural Florida, discovered federal grant money was available for rural Internet expansion as part of the Obama Administration’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The two groups fashioned a broadband proposal they were confident would win approval. At the time, rural broadband across northwest and south-central Florida was dismal at best, with only 39% of homes covered. Largely unserved by cable and barely served with DSL from AT&T and other telephone companies, the two groups believed a wireless network would be the best solution for Hardee, DeSoto, Highlands, Okeechobee, Glades, Hendry, Holmes, Washington, Jackson, Gadsden, Calhoun, Liberty, Gulf and Franklin counties.

$24 million spent and nothing to show for it.

Although $24 million is not an insubstantial sum, it was clearly never adequate to build a comprehensive rural broadband network reaching homes and businesses. Instead, the two groups envisioned a “middle mile” network funded by the government, with central offices in Orlando and Tallahassee equipped with microwave dishes and computer servers. Unlike most middle mile networks, the one proposed by the FRBA would rely on a network of microwave towers instead of fiber optics, and would ultimately serve all of its customers over a wireless network.

When complete, the wireless network was supposed to deliver up to 1Gbps capacity throughout the region, relying on leased space on existing cell towers to support microwave links that would bounce signals from one area to the next. Initially promising to serve more than 174,000 homes and 16,400 businesses, the one immediate flaw noticed by those skeptical of the proposal was the lack of a definitive plan to sell Internet service to paying residential and business customers. The brochures suggested existing commercial Internet Service Providers would magically step into that role. Early critics called that “wishful thinking.”

Despite what some felt was an untenable business plan and an incomplete application, the group won its federal “BTOP” grant of $24 million in 2010 and began a very lengthy planning process using well-paid consultants to get the network fully scoped out and built. Within a year, controversy quickly threatened to swamp the project, and a congressional oversight investigation quickly found evidence of wasteful spending and put its funding on hold. That would hardly be the first allegation raised against the FRBA and those overseeing it. By 2013, the Columbia County Observer had run more than a dozen stories reporting irregularities and other problems with the project. Few were noticed more than the report Rapid Systems, Inc., one of the contractors on the project, had filed a $25 million lawsuit replete with soap operatic allegations against FRBA for not being paid for its work.

Rapid Systems CEO, Dustin Jurman and CFO/VP Denise Hamilton. (Image: Columbia County Observer)

Rapid Systems alleged everything from fraud and double-dipping to sexual promiscuity over what it called the “FRBA Fraud Scheme.”

At the heart of the lawsuit were allegations money was being misspent, “to pay inflated salaries to employees, who then fled to South America, and that grant money was used for inflated fees to consulting companies which were owned by FRBA principals.”

Rapid Systems claimed FRBA was very generous paying management consulting fees of $10,000 a month to an entity known as the Government Service Group (GSG), along with a pro rata share (3% of the grant) for a “Grant Compliance Fee” and an additional 13% of the grant as a “Capital Improvement Program Administrative Fee.” And you thought only Comcast and Time Warner Cable were creative conjuring up fees. When added up, it appeared just one consultant — GSG — would walk away with 16% of the entire grant — nearly $4 million in total “management fees” before a single broadband connection would be made.

The lawsuit also claimed the grant money was gorged on by the leadership of both non-profits, one who allegedly relocated to South America the lawsuit states in another aside. The two “were being paid fees in the amount of $8,500 a month to themselves cloaked as administrative and community outreach funds,” according to the lawsuit.

Phillip Dampier: To be a credible supporter of community broadband, it is responsible to call out the disasters so they are not repeated.

Meanwhile, the public eagerly awaiting something better than the non-broadband AT&T and some independent phone companies were supplying in the region couldn’t get answers about the project’s progress. Neither could the media, which reported the business phone number for the FRBA would ring unanswered for hours or days. Those hired to provide community outreach about the broadband project were frequently unable to answer even basic questions about the network or its status, or where the principals involved in the project even met.

By 2014, Opportunity Florida’s Facebook page claimed the network was 90% complete. But the project now decidedly downplayed how many homes and businesses would get service. Instead, the middle mile network promoted itself as an institutional network, dedicated primarily to serving “community anchor institutions:”

The FRBA system provides lower cost, high capacity broadband to Community Anchor Institutions, commonly referred to as “CAIs.” CAIs include local government and public agencies including schools, libraries and hospitals. The NTIA grant was initiated with these unserved or underserved CAIs as the intended target. Most government and public services have moved, or are in the process of moving, to paperless transactions and record-keeping and need the additional broadband and Internet based capabilities. Another benefit of the FRBA system will be capacity to schools and libraries as both those institutions face online and digital mandates.

Commercial ISPs willing to use the network to offer service to individual non-institutional customers were invited to visit an Opportunity Florida webpage (now gone) for more information. There is no evidence any major ISP ever bothered. In fact, even institutional users didn’t seem very interested. We remain unclear if there was ever a single paying customer on the network, despite a report filed by the NFBA with the federal government that claimed through September 30, 2012, the NFBA had 11 anchor institutions, zero residents, and zero businesses hooked up to its network.

A year later, the Columbia County Observer went further and called some of those involved in evangelizing the project “clueless,” and based on the post-mortem of what has happened since, they may be right.

Those directly involved in the project have since displayed a stunning lack of knowledge about its operations and practices, or what has become of the $24 million:

The unfortunate “I see nothing, I hear nothing, I know nothing” brigade answers questions from the media.

- Gina Reynolds, the last executive director of FHREDI, which administered FRBA, claimed the network was running fine when she left in the summer of 2015 to start her own economic development consultancy. She may be among the very few that got out before the project ultimately fell apart. Although FHREDI managed to pay her for her services, it suddenly lacked any resources to pay anyone to replace her after she left;

- Greg Harris, a Highlands County commissioner and FHREDI director, disclosed at a recent county commission meeting FRBA was in Chapter 7 bankruptcy and the group that oversaw it — FHREDI, was being dissolved. But like the phoenix rising from the ashes, some of those involved in FHREDI and FRBA are now associating themselves with a new group called the Florida Heartland Economic Region of Opportunity (FHERO). Says Harris: “We didn’t really know what FHREDI was doing. They were spending most of their opportunity on FRBA and the rural broadband. It got away from what we really needed to focus on.”

- Terry Burroughs, an Okeechobee County commissioner, is FHERO’s chairman. But last year, the ex-telephone company executive was a FHREDI board member. His memory is excellent about where the taxpayer-funded equipment to run the network eventually ended up: in warehouses in Lake Placid and Tallahassee. But his answers were more vague when asked how things went so wrong. Burroughs tried to put substantial distance between himself and the failed wireless broadband network: “When I first got on the board, they were trying to negotiate with a contractor. Gina [Reynolds] was working with that, and it went on and on and on. There was probably a network at some given time, but I don’t think a last mile ever deployed. When I got there, the last mile was dark. … I never knew of a paying customer. They were trying to build a telephone company, and they were doomed to failure.”

- Paul McGehee, business development manager for Glades Electric and a FHERO director, did an even better job explaining he knew nothing, saw nothing, and heard (almost) nothing: “The operator who was contracted to run it as a company stepped away from it,” McGehee said, adding he could not recall the contractor’s name. The flaw in FRBA’s plan, according to McGehee, was that while the grant bought the equipment, there were no federal funds for operations. “No one wanted to step up and operate the network, and there was no way to pay the tower leases… The end product wasn’t a viable sustainable thing.”

Too bad nobody bothered to consider that before spending $24 million of the taxpayers’ money on a non-viable network.

Too bad nobody bothered to consider that before spending $24 million of the taxpayers’ money on a non-viable network.

Commissioner Jim Brooks didn’t seem too bothered by the admissions of total failure. After hearing an explanation about the network’s demise and the money spent on it, he told his fellow commissioners he “didn’t have a problem with it.”

A multitude of articles that have documented this disaster (including our own from September 2011) illustrates what can happen when over-enthusiastic consultants overwhelm projects with happy talk not recognized as such by a board that has little or no understanding of the technology, the broadband business, or, in this case, the project itself. The claims and projections consistently simply bore no reality… to reality. What is even more concerning is some of those consultants didn’t work for free, and may have tapped a substantial portion of the total available grant for themselves.

It is also remarkable and disappointing to read candid assessments about a project “doomed to failure” from those with direct knowledge and or involvement only after the liquidator from the federal government turns up. As stewards of public taxpayer money, one expects more than a shrug of the shoulders and a quiet shuffle dance out of FHREDI into a new, reincarnated “rural economic development” initiative. How can we trust the same mistakes won’t be made again?

We remain strong supporters of community broadband, but messes like this hand potent ammunition to corporate-ISP-funded think tanks that use these kinds of failures to sully all public broadband projects. We must call out of the bad ones to be seen as credible supporting the good ones. It also never hurts to learn from others’ mistakes.

Among the biggest reasons this project was a flop (beyond the dubious skills of those in charge of overseeing it) was its size, scope, and technology choice. The biggest challenge to any rural broadband project is always “the last mile” — the point where the connection leaves a regional fiber network and reaches a nearby neighborhood’s utility poles and finally enters your home. It also happens to be the most costly segment of the network, and often the hardest to fund with government subsidies. But it is the one that makes the difference for individual homeowners and businesses who either have broadband or don’t.

Rural Floridians endure more broken promises for better broadband.

Like too many middle mile projects of this type, the story initially fed to the press and supporters is that such networks will somehow alleviate rural broadband problems. Only later do supporters realize they are actually getting an institutional middle mile network that will offer service to hospitals, schools, and public safety buildings — not to homes and businesses. Ordinary citizens cannot access such networks unless a commercial ISP shows interest in leasing it to resell, which is unlikely. The closest most will ever get to experiencing an institutional network they paid for is staring at the fiber cable stretched across the utility poles in front of your house.

FRBA was too ambitious in size and scope, and a credible consultant should have advised those in charge to get credible evidence that a network built with grant money could be sustained without it going forward. If not, scale back the project or don’t apply for the grant.

This project proposed a wireless backbone to power a large regional wireless network. Winning support among anchor institutions was predictably difficult, because many already have existing contracts with commercial telecom companies. With government funding available in many instances, an institution can get full fiber or metro Ethernet service easier than a rural farmer can get 6Mbps DSL from a disinterested phone company.

The evidence shows there were few takers — institutional or otherwise — of what FRBA had to offer. Did the project organizers not see this lack of interest as a problem as the network prepared to launch? After launch, there were almost immediate signs it lacked enough of a customer base to sustain itself. Did the project backers assume the government would bail out the network or dump millions more into it to make it viable to sell to homes and businesses? Such assumptions would have been irresponsible.

There are too many underutilized middle mile or institutional fiber networks already built with taxpayer dollars that remain off-limits to those who paid to build them. Utilizing those networks by extending grant funding for last mile projects would be helpful, as would sufficient subsidies to assure middle mile construction is followed by last mile construction and actual service. We remain big believers in fiber to the home service. Although expensive, such projects are best positioned for success and future viability and can take advantage of the massive amount of dark fiber already laid in many areas. Some cities prefer to run the networks themselves, others contract day-to-day operations out to independent operators. Either would be preferable to a network that took six years to build and fail, without any evidence it could attract, support and sustain enough customers to support anything close to viability.

“Size-wise, they’re the Godzilla of telecommunications,” said Steve Oden, director of member services at the tiny electric co-op. “And we’re just a lowly electric co-op here in Middle Tennessee.”

“Size-wise, they’re the Godzilla of telecommunications,” said Steve Oden, director of member services at the tiny electric co-op. “And we’re just a lowly electric co-op here in Middle Tennessee.”

Subscribe

Subscribe

“Sharing is essential for the future of spectrum utilization. Many of the high-frequency bands we will make available for 5G currently have some satellite users, and some federal users, or at least the possibility of future satellite and federal users,” Wheeler noted. “This means sharing will be required between satellite and terrestrial wireless; an issue that is especially relevant in the 28GHz band. It is also a consideration in the additional bands we will identify for future exploration. We will strike a balance that offers flexibility for satellite users to expand, while providing terrestrial licensees with predictability about the areas in which satellite will locate.”

“Sharing is essential for the future of spectrum utilization. Many of the high-frequency bands we will make available for 5G currently have some satellite users, and some federal users, or at least the possibility of future satellite and federal users,” Wheeler noted. “This means sharing will be required between satellite and terrestrial wireless; an issue that is especially relevant in the 28GHz band. It is also a consideration in the additional bands we will identify for future exploration. We will strike a balance that offers flexibility for satellite users to expand, while providing terrestrial licensees with predictability about the areas in which satellite will locate.”

A word to the wise: using public money to build a middle mile broadband network without any customers lined up to sign up is a disaster waiting to happen.

A word to the wise: using public money to build a middle mile broadband network without any customers lined up to sign up is a disaster waiting to happen.

Too bad nobody bothered to consider that before spending $24 million of the taxpayers’ money on a non-viable network.

Too bad nobody bothered to consider that before spending $24 million of the taxpayers’ money on a non-viable network.

Time Warner Cable says it is forced to pay monopoly rates to rent space on North Carolina’s publicly owned utility poles and it now wants the state government to settle the issue by regulating prices to better reflect actual costs.

Time Warner Cable says it is forced to pay monopoly rates to rent space on North Carolina’s publicly owned utility poles and it now wants the state government to settle the issue by regulating prices to better reflect actual costs. The five public utilities each serve between 26,800-122,000 customers. Altogether, the five maintain 75,000 utility poles now involved in the dispute. All charge considerably more for pole rentals than Duke Energy, the state’s largest for-profit utility, which gets somewhere between $5-7 a year for each pole. Co-ops South River EMC is seeking $17.40 per year. Carteret-Craven EMC wants $23.60 a year.

The five public utilities each serve between 26,800-122,000 customers. Altogether, the five maintain 75,000 utility poles now involved in the dispute. All charge considerably more for pole rentals than Duke Energy, the state’s largest for-profit utility, which gets somewhere between $5-7 a year for each pole. Co-ops South River EMC is seeking $17.40 per year. Carteret-Craven EMC wants $23.60 a year. “In order to maintain 501(c)(12) cooperative tax-exempt status, cooperatives charge cost-based rates for their services, including pole attachments,”

“In order to maintain 501(c)(12) cooperative tax-exempt status, cooperatives charge cost-based rates for their services, including pole attachments,”

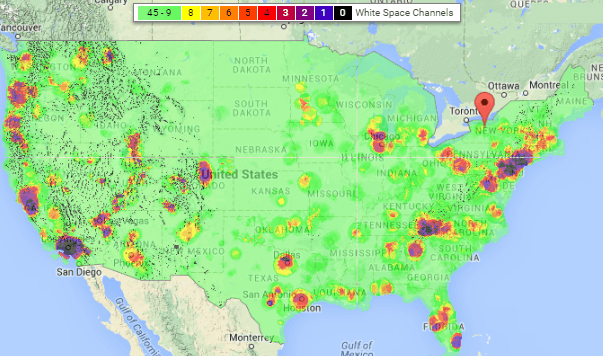

The concept of white space wireless Internet access has already taken hold in Europe but has dragged in the United States as existing UHF television stations, wireless carriers, wireless microphone manufacturers and others who use the same frequencies white space data services also depend on defend their turf. Since white space services are unlicensed and intended for two-way communications, fears that Internet users would degrade wireless microphones or TV reception meant special care had to be taken to lower the potential for interference.

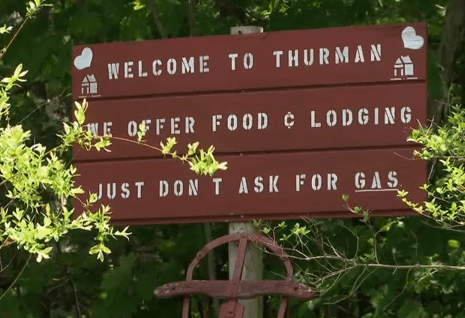

The concept of white space wireless Internet access has already taken hold in Europe but has dragged in the United States as existing UHF television stations, wireless carriers, wireless microphone manufacturers and others who use the same frequencies white space data services also depend on defend their turf. Since white space services are unlicensed and intended for two-way communications, fears that Internet users would degrade wireless microphones or TV reception meant special care had to be taken to lower the potential for interference. Since the town is located entirely within the Adirondack Park, there are prohibitions on placing communications towers on nearby peaks or other high spots that could spoil the view;

Since the town is located entirely within the Adirondack Park, there are prohibitions on placing communications towers on nearby peaks or other high spots that could spoil the view;