Once again, a writer from the corporate-funded Mercatus Center is back to shill for the telecom industry.

Once again, a writer from the corporate-funded Mercatus Center is back to shill for the telecom industry.

Eli Dourado landed space in Slate to write a ridiculous defense of Comcast’s expanding trials of usage caps. When we first read it, we assumed a Comcast press release somehow managed to find its way into the original article. It quickly became impossible to discern the difference.

Before we take apart Mr. Dourado’s nonsensical arguments, let’s consider the source.

Sourcewatch calls Mercatus one of the best-funded think tanks in the United States. And why not. Its indefatigable advocacy of pro-corporate policies is legendary. The Center itself was initially funded by the Koch Brothers to advocate against consumer protection and oversight and for deregulation.

With that kind of mission and money, it’s no surprise the authors coming out of Mercatus are in rigid lock-step with the corporate agendas of Comcast, AT&T, and other large telecom companies. The Center is also a friend of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a group that counts Comcast and AT&T as dues-paying members. ALEC’s corporate members ghostwrite legislation that ends up introduced in state legislatures across the country.

We have never seen a Mercatus-affiliated author ever write a piece that runs contrary to the interests of Big Telecom companies. They oppose community broadband competition, Net Neutrality, and have defended wireless mergers that would have killed T-Mobile, turn Time Warner customers into Comcast customers, and believed AT&T’s buyout of DirecTV was just dandy and Charter’s buyout of Time Warner Cable is even more consumer-y.

They favor usage caps/usage pricing, defend higher bills, and laughingly claim Americans are probably underpaying for broadband compared to the rest of the world.

Life must be good on Broadband Fantasy Island, where those in favor of Comcast’s usage pricing experiments live. In a style that eerily resembles a Comcast corporate blog post, Dourado unconvincingly tells readers, “metered data is good for most consumers and for the Internet.”

Dourado’s defense of Comcast’s idea of reasonable pricing only had one slip-up, when he accidentally told the truth. He effectively derailed Comcast’s usual talking point that “it is only fair for heavy users to pay more” when he correctly noted, “broadband networks are composed almost entirely of fixed costs—costs that don’t vary very much with usage.”

(Image: Jacki Gallagher)

That ripping sound you hear is a corporate executive starting to tear up their contribution check to Mercatus Center for being off message. But hang on, Mr. Corporate Guy, Mercatus Center has always had your back before, let’s see if Dourado can pull his feet out of the fire.

“But when users pay for data use, cable companies have an incentive to make it easier than ever to use a lot of data—that is, to invest in speed upgrades. They want you to blow right by your habitual usage amounts, which you will probably do only if you are on a superfast connection. In this way, metered data encourages broadband network upgrades,” Dourado claims, back on message.

Dourado’s core argument is one we’ve heard from telecom companies for years: heavy users are responsible for the allegedly high fixed costs of delivering broadband to America. Because networks must be built to accommodate all users, those ‘data hogs’ force providers to charge top dollar to everyone to assure access to promised speeds, unfairly penalizing light users like grandma along the way just to satiate someone else’s desire for more downloading.

If that were true, broadband costs everywhere would be around the same and Frontier’s DSL service wouldn’t be so universally awful. Unfortunately for Dourado’s argument, we have the ability to look at broadband pricing and service quality beyond the monopoly/duopoly marketplace we have in North America. Fixed costs to deliver broadband service here are comparable in western Europe and Asia and somehow they manage to do a lot more for a lot less.

If that were true, broadband costs everywhere would be around the same and Frontier’s DSL service wouldn’t be so universally awful. Unfortunately for Dourado’s argument, we have the ability to look at broadband pricing and service quality beyond the monopoly/duopoly marketplace we have in North America. Fixed costs to deliver broadband service here are comparable in western Europe and Asia and somehow they manage to do a lot more for a lot less.

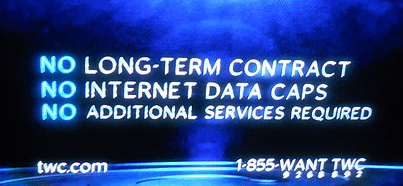

Closer to home, newly emerging competitors like Google Fiber, municipal/community broadband, and private overbuilders like Grande Communications and WOW! also manage to deliver more service for less money, without any need to gouge and abuse their customers. The fact Time Warner Cable, Verizon, Charter and Bright House have seen no need to impose compulsory usage caps or usage pricing (AT&T does not enforce their cap on U-verse service either) and also do business in the same states where Comcast is imposing caps is just the first of many threads that unravel Dourado’s poorly woven argument.

Let’s break Dourado’s other arguments down:

Phillip Dampier

Dourado’s Claim: “Broadband networks are composed almost entirely of fixed costs—costs that don’t vary very much with usage. Cable companies have to spend many billions of dollars to build and maintain their networks whether or not we use them. One way or another, users of the network have to collectively pay those billions of dollars.”

Stop the Cap!: This is true, but Mr. Dourado forgets to mention most of the costs to construct those networks were paid off years ago. DSL and fiber to the neighborhood services avoided incurring the most costly part of network construction — wiring the last mile to the customer’s home. Phone company broadband, excepting Verizon’s complete fiber-to-the-home service network overhaul, benefits from the use of an existing copper-based network built and paid for long ago to deliver basic telephone service.

The cable industry did even better. It used the same fiber-coax network last rebuilt in the early/mid-1990s to deliver more television channels to also deliver broadband, which initially took up about as much space as just one or two TV channels. The cable industry introduced broadband experimentally, spending comparatively little on network upgrades. This was important to help overcome skepticism by corporate executives who initially doubted selling Internet access over cable would ever attract much interest. It shows how much they know.

So while it is true to say the telecommunications industry spent billions to develop their infrastructure, for most it was primarily to sell different services — voice grade telephone service and cable-TV, for which it received a healthy return. Selling broadband turned out to be added gravy. For a service the cable industry spent relatively little to offer, it collected an average of $30 a month in unregulated revenue. That price has since doubled (or more) for many consumers. Cost recovery has never been a problem for companies like Comcast.

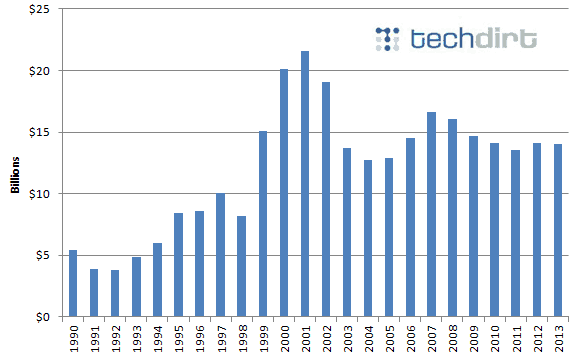

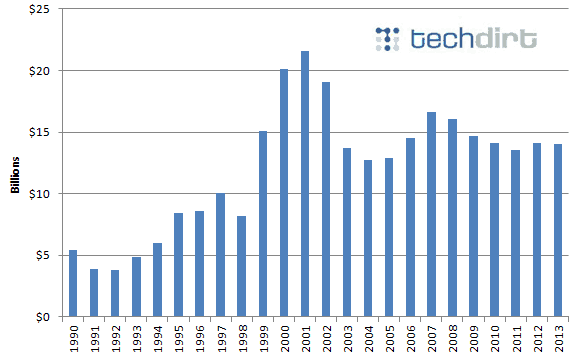

In 2014, Techdirt showed broadband investment wasn’t increasing at the rate the cable industry claimed. It has been largely flat, and not because of broadband usage or pricing.

It is easy for providers to show eye-popping dollar amounts invested in broadband improvements. Most providers routinely quote these numbers to justify just about everything from rate increases to further deregulation. When the numbers alone don’t sufficiently sell their latest argument, they lie about them. Adopting any pro-consumer policy like Net Neutrality or a ban on usage pricing would, in their view, “harm investment.” Only it didn’t and it won’t.

What these same providers never include on those press releases are their revenue numbers. Placed side by side with capital expenses/infrastructure upgrades, the clarity that emerges from showing how much providers are putting in the bank takes the wind right out of their sails. It turns out most providers are already earning a windfall selling unlimited broadband at ever-rising prices, while network upgrade expenses remain largely flat or are in decline. In short, your phone or cable company is earning a growing percentage of their overall profits from the sale of broadband, because they are raising prices while also enjoying an ongoing decline in the cost of providing the service. Despite that, they are now back for more of your money.

Dourado’s basic argument is the same one providers have tried for years — attempting to pit one customer against another over who is responsible for the high cost of Internet access. They prefer to frame the argument as “heavy users” vs. “light users.” Hence, it is isn’t fair to expect grandma to pay for the teen gamer down the street who also enjoys BitTorrent file sharing. Their hope is that the time-tested meme “someone is getting a free ride while you pay for it” will act like shiny keys to distract people from fingering the real perpetrator of high pricing — the same phone and cable companies laughing all the way to the bank.

It’s easy to prove and we’ve done it here at Stop the Cap! since 2008.

We have a BS detector that never fails to uncover the real motivation behind usage pricing. It’s simply this. If a provider is really in favor of usage billing, then let’s have a go at it. But it must be real usage pricing.

We have a BS detector that never fails to uncover the real motivation behind usage pricing. It’s simply this. If a provider is really in favor of usage billing, then let’s have a go at it. But it must be real usage pricing.

Here’s how it works. Just as with your electric utility, you will pay a monthly connection/facilities charge to cover the cost of the transport network and infrastructure, typically $15 or less per month (and it should be less because utilities have to maintain physical meters that cable and phone companies don’t). Next come usage charges, and because the industry seems to have adopted AT&T’s formula, we will use that.

Your broadband will now cost $15 a month for the connection charge and usage pricing will amount to $10 for each 50GB increment of usage. Because even Mr. Dourado admits there is no real cost difference supplying broadband at different speeds, you deserve the maximum. If you turn in average usage numbers, you will have consumed between 50-100GB each month. So your new broadband bill will be $25 if you consume 50 or fewer gigabytes, $35 if you consume between 50-100GB. Deal?

Considering what you are probably paying today for Internet access, you will fully understand that howling sound you hear is coming from telecom company executives screaming in opposition to fair usage pricing. That is why no provider in America is advocating for fair usage pricing. In reality, they want to charge current prices –and– impose an arbitrary usage allowance on you, above which they can begin to collect overlimit penalty fees. It’s just another rate hike.

Dourado is stuck with a bad hand trying to play the second part of the “usage pricing fairness” game. While claiming heavy users should be forced to pay more, he is unable to offer a real example of light users paying substantially less.

At this point, Dourado’s proverbial pants fall off, exposing the naked reality that few, if any customers actually pay less under usage pricing. That is because providers are terrified of the word “cannibalization.” In the broadband business, it refers to customers examining their options and downgrading their service to a cheaper-priced plan (shudder) that better reflects their actual usage. To make certain this happens rarely, if ever, Comcast offers customers scant savings of $5 from exactly one “Flexible Data Option” available only to those choosing the improbable Economy Plus plan, which offers just 3Mbps service. Customers agree to keep their usage at or below 5GB a month or they risk an overlimit fee of $1 per gigabyte. It’s like Russian Roulette for Bill Shock. Where can we sign up?

At this point, Dourado’s proverbial pants fall off, exposing the naked reality that few, if any customers actually pay less under usage pricing. That is because providers are terrified of the word “cannibalization.” In the broadband business, it refers to customers examining their options and downgrading their service to a cheaper-priced plan (shudder) that better reflects their actual usage. To make certain this happens rarely, if ever, Comcast offers customers scant savings of $5 from exactly one “Flexible Data Option” available only to those choosing the improbable Economy Plus plan, which offers just 3Mbps service. Customers agree to keep their usage at or below 5GB a month or they risk an overlimit fee of $1 per gigabyte. It’s like Russian Roulette for Bill Shock. Where can we sign up?

In fact, Time Warner Cable has already admitted a similar plan open to all of its broadband customers was a colossal flop, attracting only “a few thousand” customers nationwide out of 15 million qualified to choose it. We suspect the number of Comcast customers signed up to this “money-saving plan” is probably in the hundreds. Time Warner was smart enough to realize forcing customers into a massively unpopular compulsory usage plan would make them a pariah. For Comcast, “pariah” is a matter of “same story, different day.” Alienating customers is their specialty and despite growing customer dissatisfaction, executives have ordered all ahead full on usage pricing.

Dourado also can’t help himself, getting his own cheap shot in at government-mandated Lifeline-like discounts designed to make Internet access more affordable, calling it a “tax and spend program.” He omits the fact Comcast already offers its own affordable Internet plan voluntarily. But mentioning that would further undercut his already weak argument in favor of usage pricing.

Dourado: “If everyone paid equal prices for unlimited data plans, cable company revenues would be limited by the number of people willing to pay that equal rate.”

Stop the Cap!: Providers have already figured out they can charge higher prices for all sorts of things to increase revenue. General rate increases, modem fees, and charging higher prices for faster speeds are also proven ways companies are earning higher revenue from their existing customers.

Dourado: “But when users pay for data use, cable companies have an incentive to make it easier than ever to use a lot of data—that is, to invest in speed upgrades. They want you to blow right by your habitual usage amounts, which you will probably do only if you are on a superfast connection. In this way, metered data encourages broadband network upgrades.”

Stop the Cap!: Nice theory, but companies like Comcast have found an easier way to make money. They simply raise the price of service. Dourado should learn more about the concept of pricing elasticity. Comcast executives know all about it. It allows them, in the absence of significant competition, to raise broadband prices just because they can and not risk significant customer number defections as a result.

Stop the Cap!: Nice theory, but companies like Comcast have found an easier way to make money. They simply raise the price of service. Dourado should learn more about the concept of pricing elasticity. Comcast executives know all about it. It allows them, in the absence of significant competition, to raise broadband prices just because they can and not risk significant customer number defections as a result.

After they do that, the next trick in the book is to play games with usage allowances to expose more customers to overlimit fees or force them into more expensive usage plans. In Atlanta, Comcast even sells its own insurance plan to protect customers… from Comcast. For an extra $35 a month, customers can avoid being molested by Comcast’s arbitrary usage allowance and overlimit fees and get unlimited service back. As customers rightfully point out, this means they are paying $35 more a month for the same service they had just a few months earlier, with no improvements whatsoever. Is that innovative pricing or highway robbery?

What inspires companies to raise speeds and treat customers right is competition, something sorely lacking in this country. Just the vaguest threat of a new competitor, such as the arrival of Google Fiber was more than enough incentive for companies to begin investing in waves of speed upgrades, bringing some customers gigabit speeds. Usage pricing played no factor in these upgrades. The fact a new competitor threatened to sell faster Internet at a fair price (without caps) did.

Dourado: “The DOCSIS 3.1 cable modem standard, just now being finalized, will allow downloads over the existing cable network up to 10 Gbps (10 times faster than Google Fiber). Cable companies are now facing a choice as to how fast to roll out support for DOCSIS 3.1. As the theory predicts, Comcast, now experimenting with metering, is planning an aggressive rollout of the new multi-gigabit standard.”

Stop the Cap!: While Dourado celebrates Comcast’s achievements, he ignores the fact EPB Fiber in Chattanooga offers 10Gbps fiber broadband today, charging the same price Comcast wants for only 2Gbps service, and does not charge Comcast’s $1,000 installation and activation fee. EPB did not require the incentive of usage billing or caps to finance its upgrade. Dourado also conveniently ignores the fact almost every cable operator, many with no plans to add compulsory usage caps or usage pricing, are also aggressively moving forward on plans to rollout DOCSIS 3.1. It’s more efficient, allows for the sale of more profitable higher speed Internet tiers, and is cost-effective. Some companies want the right to gouge their customers, others want to do the right thing. Guess where Comcast fits.

Usage Cap Man

Dourado: “It’s not fun to continually calculate how much you are spending. But we all gladly accept metering for water and electricity with no significant mental accounting costs—why should broadband be so different? Both Comcast and Cox make it easy to track usage. And even if we can’t just get over our mental accounting costs, are they really so significant that we should cite them as an excuse for keeping the poor and elderly offline and letting our broadband networks stagnate?”

Stop the Cap!: Assumes facts not in evidence. First, once again Mr. Dourado’s talking points come straight from the cable industry and are fatally flawed. While Dourado talks about usage pricing for water and electricity — resources that come with the added costs of being pumped, treated, or generated, he conveniently ignores the one service most closely related to broadband – the telephone. The costs to transport data, whether it is a phone call or a Netflix movie, have dropped so much, phone companies increasingly offer unlimited local -and- long distance calling plans to their customers. When is the last time anyone bothered to think about calling after 11pm to get the “night/weekend long distance rate?” For years, broadband customers have not had to worry how much a Netflix movie will chew through a broadband usage allowance either. But now they might, because the cable industry understands that Netflix viewer may have cut his cable television package, cutting the revenue the cable company now wants back.

Second, heavy Internet users are not the ones responsible for keeping the poor and elderly offline and allowing broadband infrastructure to stagnate. The blame for that lies squarely in the executive suites at Comcast, AT&T and other telecom companies that make a conscious business decision charging prices that guarantee better returns for their shareholders (and their fat executive salary and bonuses).

But it isn’t all bad news.

Comcast’s Internet Essentials already exists today and is priced at $9.95 a month. Only Comcast’s revenue-cannibalization protection scheme keep it out of the hands of more customers. It limits the program to customers with school age children on the federal student lunch program and is off-limits to existing Comcast broadband customers even if they otherwise qualify. Why? Because if the program was available to everyone, it would quickly cut their profits as customers downgraded their service.

Comcast’s abysmal performance is legendary, and that isn’t a result of heavy users either. That is entirely the fault of a company that puts its own greed ahead of its alienated customers, something plainly clear from forcing captive customers into usage trials they don’t want or need. Verizon FiOS uses technology far superior to what Comcast is using, offers better speeds and better service. Customers are happy and routinely rate FiOS among the nation’s top providers. They don’t need usage pricing or caps to manage this. Comcast sure doesn’t either.

Mr. Dourado’s arguments for usage pricing are so weak and provably false, it is almost embarrassing. But we understood he was given the impossible challenge trying to mount a defense for Comcast’s latest Internet Overcharging scheme. Nobody can defend the indefensible.

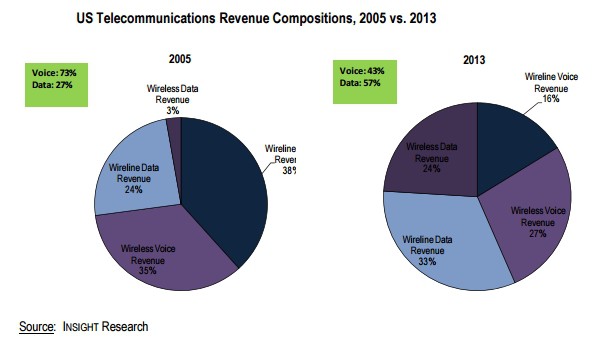

The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time, the volume of domestic telephone calls and the revenue generated from them was nearly flat. For the last two years, both are now in decline on the wireless side of the business as North Americans increasingly stop talking on the phone and text and message instead.

The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time, the volume of domestic telephone calls and the revenue generated from them was nearly flat. For the last two years, both are now in decline on the wireless side of the business as North Americans increasingly stop talking on the phone and text and message instead. Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging.

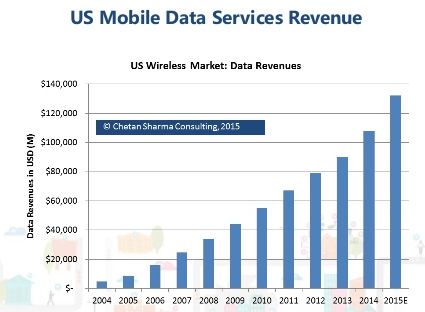

Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging. The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier.

The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier. Some even expect carriers to eventually embrace Wi-Fi calling, declaring it superior to alternatives like Hangouts and Skype, which require an app to handle the call. A Wi-Fi call can be received by anyone with a phone.

Some even expect carriers to eventually embrace Wi-Fi calling, declaring it superior to alternatives like Hangouts and Skype, which require an app to handle the call. A Wi-Fi call can be received by anyone with a phone.

Subscribe

Subscribe Since Verizon Wireless stopped selling unlimited data plans and turned data into a precious commodity usually worth about $10 per gigabyte, the company can afford to give some of it away to their loyal customers.

Since Verizon Wireless stopped selling unlimited data plans and turned data into a precious commodity usually worth about $10 per gigabyte, the company can afford to give some of it away to their loyal customers. Once again, a writer from the corporate-funded Mercatus Center is back to shill for the telecom industry.

Once again, a writer from the corporate-funded Mercatus Center is back to shill for the telecom industry.

If that were true, broadband costs everywhere would be around the same and Frontier’s DSL service wouldn’t be so universally awful. Unfortunately for Dourado’s argument, we have the ability to look at broadband pricing and service quality beyond the monopoly/duopoly marketplace we have in North America. Fixed costs to deliver broadband service here are comparable in western Europe and Asia and somehow they manage to do a lot more for a lot less.

If that were true, broadband costs everywhere would be around the same and Frontier’s DSL service wouldn’t be so universally awful. Unfortunately for Dourado’s argument, we have the ability to look at broadband pricing and service quality beyond the monopoly/duopoly marketplace we have in North America. Fixed costs to deliver broadband service here are comparable in western Europe and Asia and somehow they manage to do a lot more for a lot less.

We have a BS detector that never fails to uncover the real motivation behind usage pricing. It’s simply this. If a provider is really in favor of usage billing, then let’s have a go at it. But it must be real usage pricing.

We have a BS detector that never fails to uncover the real motivation behind usage pricing. It’s simply this. If a provider is really in favor of usage billing, then let’s have a go at it. But it must be real usage pricing. At this point, Dourado’s proverbial pants fall off, exposing the naked reality that few, if any customers actually pay less under usage pricing. That is because providers are terrified of the word “cannibalization.” In the broadband business, it refers to customers examining their options and downgrading their service to a cheaper-priced plan (shudder) that better reflects their actual usage. To make certain this happens rarely, if ever, Comcast offers customers scant savings of $5 from exactly one “

At this point, Dourado’s proverbial pants fall off, exposing the naked reality that few, if any customers actually pay less under usage pricing. That is because providers are terrified of the word “cannibalization.” In the broadband business, it refers to customers examining their options and downgrading their service to a cheaper-priced plan (shudder) that better reflects their actual usage. To make certain this happens rarely, if ever, Comcast offers customers scant savings of $5 from exactly one “ Stop the Cap!: Nice theory, but companies like Comcast have found an easier way to make money. They simply raise the price of service. Dourado should learn more about the concept of pricing elasticity. Comcast executives know all about it. It allows them, in the absence of significant competition, to raise broadband prices just because they can and not risk significant customer number defections as a result.

Stop the Cap!: Nice theory, but companies like Comcast have found an easier way to make money. They simply raise the price of service. Dourado should learn more about the concept of pricing elasticity. Comcast executives know all about it. It allows them, in the absence of significant competition, to raise broadband prices just because they can and not risk significant customer number defections as a result.

Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint

Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint  Time Warner Cable will continue to offer customers unlimited data plans and further expand its Maxx upgrade program until it reaches the company’s entire service area or the merger with Charter Communications is approved by regulators.

Time Warner Cable will continue to offer customers unlimited data plans and further expand its Maxx upgrade program until it reaches the company’s entire service area or the merger with Charter Communications is approved by regulators.