Phillip "Is this 'innovation' or more 'alienation' from Big Cable" Dampier

While Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski pals around with his cable industry friends at this week’s Cable Show in Boston, observers could not miss the irony of the current FCC chairman nodding in repeated agreement with former FCC chairman Michael Powell, whose bread is now buttered by the industry he used to regulate.

The revolving door remains well-greased at the FCC, with Mr. Powell assuming the role of chief lobbyist for the cable industry’s National Cable and Telecommunications Association (and as convention host) and former commissioner Meredith Attwell-Baker enjoying her new office and high priced position at Comcast Corporation, just months after voting to approve its multi-billion dollar merger with NBC-Universal.

Genachowski’s announcement that he favors “usage-based pricing” as healthy and beneficial for broadband and high-tech industries reflects the view of a man who doesn’t worry about his monthly broadband bill. As long as he works for taxpayers, we’re covering most of those expenses for him.

Former FCC chairman Powell said cable providers want to be able to experiment with pricing broadband by usage. That represents the first step towards monetizing broadband usage, an alarming development for consumers and a welcome one for Wall Street who understands the increased earnings that will bring.

Unfortunately, the unspoken truth is the majority of consumers who endure these “experiments” are unwilling participants. The plan is to transform today’s broadband Internet ecosystem into one checked by usage gauges, rationing, bill shock, and reduced innovation. The director of the FCC’s National Broadband Plan, Blair Levin, recently warned the United States is on the verge of throwing away its leadership in online innovation, distracted trying to cope with a regime of usage limits that will force every developer and content producer to focus primarily on living within the usage allowances providers allow their customers.

“I’d rather be the country that developed fantastic applications that everyone in the world wants to use than the country that only invented data compression technology [to reduce usage],” Levin said.

Genachowski’s performance in Boston displayed a public servant primarily concerned about the business models of the companies he is supposed to oversee.

Genachowski: Abdicating his responsibility to protect the public in favor of the interests of the cable industry.

“Business model innovation is very important,” Genachowski said. “There was a point of view a couple years ago that there was only one permissible pricing model for broadband. I didn’t agree.”

We are still trying to determine what Genachowski is talking about. In fact, providers offer numerous pricing models for broadband service in the United States, almost uniformly around speed-based tiers, which offer customers both a choice in pricing and includes a worry-free usage cap defined by the maximum speed the connection supports.

Broadband providers experimenting with Internet Overcharging schemes like usage caps, speed throttles, and usage-billing only layer an additional profit incentive or cost control measure on top of existing pricing models. A usage cap limits a customer to a completely arbitrary level of usage a provider determines is sufficient. But such caps can also be used to control over-the-top streaming video by limiting its consumption — an important matter for companies witnessing a decline in cable television customers. Speed throttles are a punishing reminder to customers who “use too much” they need to ration their usage to avoid being reduced to mind-numbing dial-up speeds until the next billing cycle begins. Usage billing discourages consumers from ever trying new and innovative services that could potentially chew up their allowance and deliver bill shock when overlimit fees appear on the bill.

The industry continues to justify these experiments with wild claims of congestion, which do not prevent companies like Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Cox from sponsoring their own online video streaming services which even they admit burn through bandwidth. Others claim customers should pay for what they use, which is exactly what they do today when they write a check to cover their growing monthly bill. Broadband pricing is not falling in the United States, it is rising — even in places where companies claim these pricing schemes are designed to save customers money. The only money saved is that not spent on network improvements companies can now delay by artificially reducing demand.

It’s having your cake and eating it too, and this is one expensive cake.

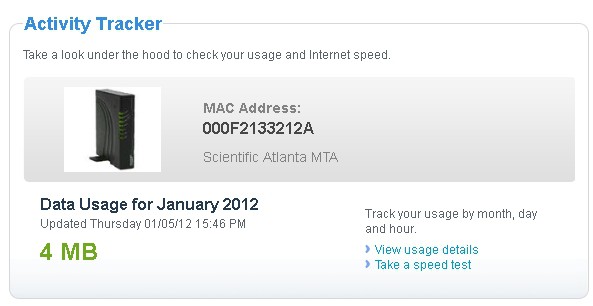

Comcast is selling broadband service for $40-50 that one research report found only costs them $8 a month to provide. That’s quite a markup, but it never seems to be enough. Now Comcast claims it is ditching its usage cap (it is not), raising usage allowances (by 50GB — four years after introducing a cap the company said it would regularly revisit), and testing a new Internet overlimit usage fee it literally stole from AT&T’s bean counters (a whopping $10 for an anti-granular 50GB).

In my life, all of the trials and experiments I have participated in have been voluntary. But the cable industry (outside of Time Warner Cable, for the moment) has a garlic-to-a-vampire reaction to the concept of “opting out,” and customers are told they will participate and they’ll like it. Pay for what you use! (-at our inflated prices, with a usage limit that was not there yesterday, and an overlimit fee for transgressors that is here today. Does not, under any circumstances, apply to our cable television service.)

No wonder Americans despise cable companies.

Michael Powell, former FCC chairman, is now the host and chief lobbyist for the National Cable & Telecommunications Association's Cable Show in Boston. (Photo courtesy: NCTA)

For some reason, Chairman Genachowski cannot absorb the pocket-picking-potential usage billing offers an industry that is insatiable for enormous profits and faces little competition.

Should consumers be allowed to pay for broadband in different ways? Sure. Must they be compelled into usage pricing schemes they want no part of? No, but that’s too far into the tall grass for the guy overseeing the FCC and the market players to demand.

Of course, we’ve been here and done this all before.

America’s dinosaur phone companies have been grappling with the mysterious concept of ‘flat-rate envy’ for more than 100 years, and they made billions from delivering it. While the propaganda department at the NCTA conflates broadband usage with water, gas, and electricity, they always avoid comparing broadband with its closest technological relative: the telephone. It gets hard to argue broadband is a precious, limited resource when your local phone company is pelting you with offers for unlimited local and long distance calling plans. Thankfully, a nuclear power plant or “clean coal” isn’t required to generate a high-powered dial tone and telephone call tsunamis are rarely a problem for companies that upgraded networks long ago to keep up with demand. Long distance rates went down and have now become as rare as a rotary dial phone.

In the 20th century, landline telephone companies grappled with how to price their service to consumers. Businesses paid “tariff” rates which typically amount to 7-10 cents per minute for phone calls. But residential customers, particularly those outside of the largest cities, were offered the opportunity to choose flat-rate local calling service. Customers were also offered measured rate services that either charged a flat rate per call or offered one or two tiers of calling allowances, above which consumers paid for each additional local call.

Consumers given the choice overwhelmingly picked flat-rate service, even in cases where their calling patterns proved they would save money with a measured rate plan.

"All you can eat" pricing is increasingly common with phone service, the closest cousin to broadband.

The concept baffled the economic intelligentsia who wondered why consumers would purposefully pay more for a service than they had to. A series of studies were commissioned to explore the psychology of flat-rate pricing, and the results were consistent: customers wanted the peace of mind a predictable price for service would deliver, and did not want to think twice about using a service out of fear it would increase their monthly bill.

In most cases, flat rate service has delivered a gold mine of profits for companies that offer it. It makes billing simple and delivers consistent financial results. But there occasionally comes a time when the economics of flat-rate service increasingly does not make sense to the company or its shareholders. That typically happens when the costs to provide the service are increasing and the ability to raise flat rates to a new price point is constrained. Neither has been true in any respect for the cable broadband business, where costs to provide the service continue to decline on a per-customer basis and rates have continued to increase for consumers. The other warning sign is when economic projections show an even greater amount of revenue and profits can be earned by measuring and monetizing a service experiencing high growth in usage. Why leave money on the table, Wall Street asks.

That leaves us with companies that used to make plenty of profit charging $50 a month for flat rate broadband, now under pressure to still charge $50, but impose usage limits that reduce costs and set the stage for rapacious profit-taking when customers blow through their usage caps. It also delivers a useful fringe benefit by keeping high bandwidth content companies from entering the marketplace, as consumers fret about their impact on monthly usage allowances. Nothing eats a usage allowance like online video. Limit it and companies can also limit cable-TV cord-cutting.

Fabian Herweg and Konrad Mierendorff at the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich found the economics of flat rate pricing still work well for providers and customers, who clearly prefer unlimited-use pricing:

We developed a model of firm pricing and consumer choice, where consumers are loss averse and uncertain about their own future demand. We showed that loss-averse consumers are biased in favor of flat-rate contracts: a loss-averse consumer may prefer a flat-rate contract to a measured tariff before learning his preferences even though the expected consumption would be cheaper with the measured tariff than with the flat rate. Moreover, the optimal pricing strategy of a monopolistic supplier when consumers are loss averse is analyzed. The optimal two-part tariff is a flat-rate contract if marginal costs are low and if consumers value sufficiently the insurance provided by the flat-rate contract. A flat-rate contract insures a loss-averse consumer against fluctuations in his billing amounts and this insurance is particularly valuable when loss aversion is intense or demand is highly uncertain.

Applied to broadband, Herweg and Mierendorff’s conclusions fit almost perfectly:

- Consumers often do not understand the measurement units of broadband usage and do not want to learn them (gigabytes, megabytes, etc.)

- Consumers cannot predict a consistent level of usage demand, leading to disturbing wild fluctuations in billing under usage-based pricing;

- The peace of mind, or “insurance” factor, gives consumers an expected stable bill for service, which they prefer over unstable usage fees, even if lower than flat rate;

- Flat rate works in an industry with stable or declining marginal costs. Incremental technology upgrades and falling broadband delivery costs offer the cable industry exceptional profits even at flat-rate prices.

Time Warner Cable (for now) is proposing usage-based pricing as an option, while leaving flat rate broadband a choice on the service menu. But will it last?

Time Warner Cable (so far) is the only cable operator in the country that has announced a usage-based pricing experiment that it claims is completely optional, and will not impact on the broadband rates of current flat rate customers. If this remains the case, the cable operator will have taken the first step to successfully duplicate the pricing model of traditional phone company calling plans, offering price-sensitive light users a measured usage plan and risk-averse customers a flat-rate plan. The unfortunate pressure and temptation to eliminate the flat rate pricing plan remains, however. Company CEO Glenn Britt routinely talks of favoring usage-based pricing and Wall Street continues to pressure the company to exclusively adopt those metered plans to increase profits.

Other cable operators compel customers to adopt both speed and usage-based plans, which often require a customer to either ration usage to avoid an overlimit fee or compel an expensive service upgrade for a more generous allowance. The result is customers are stuck with plans they do not want that deliver little or no savings and often cost much more.

Why wouldn’t a company sell you a plan you want? Either because they cannot afford to or because they can make a lot more selling you something else. Guess which is true here?

Broadband threatens to not be an American success story if current industry plans to further monetize usage come to fruition. The United States is already falling behind in global broadband rankings. In fact, the countries that lived under congestion and capacity-induced usage limits in the last decade are rapidly moving to discard them altogether, even as providers in this country seek to adopt them. That is an ominous sign that destroys this country’s lead role in online innovation. How will consumers react to tele-medicine, education, and entertainment services of the future that will eat away at your usage allowance?

Even worse, with no evidence of a broadband capacity problem in the United States, Mr. Genachowski’s apparent ignorance of the anti-competitive duopoly’s influence on pricing power is frankly disturbing. Why innovate prices down in a market where most Americans have just one or two choices for service? Economic theory tells us that in the absence of regulatory oversight or additional competition, prices have nowhere to go but up.

To believe otherwise is to consider your local cable operator the guardian angel of your wallet, and just about every American with a cable bill knows that is about as real as the tooth fairy.

Subscribe

Subscribe