Would you be surprised to learn a company with just a basic, outdated website replete with spelling and grammar errors holds at least 760 television station construction permits and licenses and just wrote a check for $46.5 million to buy 52 more stations from nine different owners, with plans to shut every last one of them down in the future?

Would you be surprised to learn a company with just a basic, outdated website replete with spelling and grammar errors holds at least 760 television station construction permits and licenses and just wrote a check for $46.5 million to buy 52 more stations from nine different owners, with plans to shut every last one of them down in the future?

That is precisely the business plan of “Landover Wireless Corp.” and its series of limited liability corporate entities, which are grabbing up as much UHF television spectrum they can apply for across the country.

They are not alone.

CTB Spectrum Services, a company associated with Landover 2 LLC, has 356 UHF TV construction permits/licenses. Its website offers slightly more information about its operations, but not much.

CTB Spectrum Services, a company associated with Landover 2 LLC, has 356 UHF TV construction permits/licenses. Its website offers slightly more information about its operations, but not much.

DTV America, a mysterious Sunrise, Fla.-based venture with an official mailing address of 12717 W. Sunrise Boulevard (Suite 372) has its headquarters inside a private mailbox at a UPS Store. The company also has countless requests for television licenses on the UHF dial. DTV America manager John Kyle is also listed as chairman and president of The Pharmacy Television Network, which appears to broadcast its programming on video displays inside pharmacies. DTV America has the lowest profile of all three companies, with no apparent website.

And you thought over the air television was dead.

DTV America’s home is inside a mailbox at the UPS Store in Sunrise, Fla.

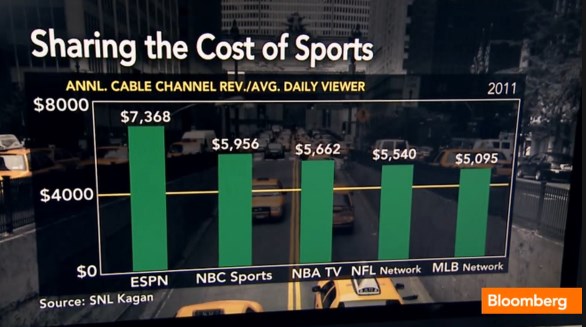

A number of low power television owners are surprised to see the sudden rush to launch more than 1,000 new television stations across the country, particularly in rural markets that have been considered a financial dead-end for low power television. Being in the LPTV business and making a living at it often depends on whether a local cable company or satellite dish provider will pick up and relay the station to the majority of Americans that do all of their television viewing on a paid platform. Without this carriage, low power television outlets have several strikes against them: challenging reception from operating with relatively low power, the lack of compelling programming — many of these outlets air paid religious, home shopping, music, or infomercial programming 24 hours a day, and the lack of familiarity by viewers who may not realize these stations are on the air.

From information Stop the Cap! has obtained, none of these ventures actually intend to stay in the over-the-air television business. Instead, they are using FCC licensing rules to get valuable UHF spectrum without having to bid for it at forthcoming spectrum auctions. At least two of the companies claim they are raising capital to build a unicast 4G wireless content delivery network. But some critics contend they are actually spectrum squatters — speculators that have no intention of building anything. Instead, critics charge they will conduct minor experiments to effectively stall the FCC, hanging onto their permits and licenses until they can sell their holdings to a wireless provider hungry for 500-700MHz spectrum and willing to pay top dollar to get it.

Meanwhile, Landover’s $46.5 million buys them dozens of low power stations airing 30-minute commercials like “Skin Solutions by Dr. Graf.” The company claims it will keep those stations on the air until their wireless network is ready, and then the infomercials (along with the rest of the television programming) will be gone for good. Landover also managed to acquire larger Class A TV stations as part of the deal, including one each in Las Vegas and Sacramento, and three in Texas. These stations might become part of the company’s 4G network, sold off or compensated to sign-off forever as part of forthcoming “spectrum packing” by the FCC — further shrinking the UHF TV dial and auctioning off the “excess” spectrum to AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and other cell companies.

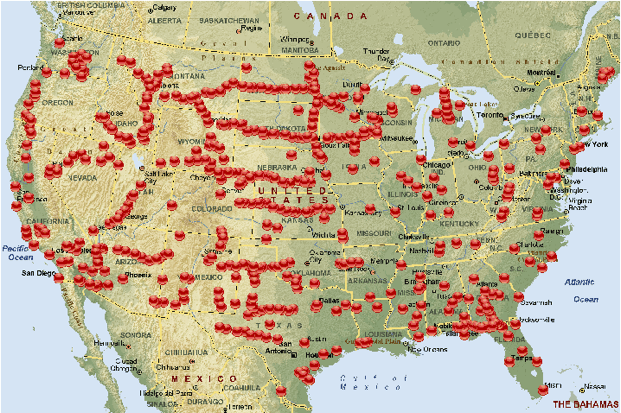

CTB’s License Map

CTB also holds multiple TV licenses in several of its markets. The company claims it will combine those stations together in something akin to a high-powered cellular network to create a bigger wireless data pipe using “patent pending multi-frequency cellular terrestrial network technology [that] increases capacity by hundreds of times through frequency re-use, while also enabling full mobility, broadband Internet, and location-based services.”

CTB’s sales pitch claims its TV licenses offer up to 228MHz of bandwidth that is “essentially identical to 700MHz spectrum, but can be acquired at a fraction of the cost.” The company also claims it has exclusive rights to TV “White Space” spectrum via first adjacent channels, which are treated like guard bands to protect against interference from nearby stations.

All of these companies are applying for channels largely in low-interest rural markets, where they face few challenges from competing applicants. CTB calls this part of their rural “corridor” strategy. One such corridor covers stations in a line from Wisconsin west to Idaho.

All three companies are betting the FCC will allow them to eventually convert their over-the-air television licenses into wireless data networks, or let them sell the spectrum to deeper pocketed players in keeping with the Commission’s plan to open up more frequencies for data-hungry users. If the FCC allows it, these three entities will end up with the rights to prime wireless spectrum covering up to 90 percent of the country without having to spend a penny at forthcoming spectrum auctions.

But there are financial risks. The type of low power station licenses held by most of these companies do not get them a seat at the spectrum packing table. LPTV outlets are considered low-priority stations, and in larger communities, many could be forced off the air without compensation to make enough room for more important, full power stations.

No license, no 4G data network for Landover, CTB and others. But the chances of that happening in rural markets, where residents are lucky to have two or three over the air stations, are slim.

The technology might offer unique broadband opportunities for rural areas where conventional low-range cell towers are too expensive, if the technology works. A higher powered transmitter serving a rural, larger geographic area might prove financially attractive in low population density areas. Only time will tell if any of these entities will be able to raise the capital needed to fulfill the FCC’s construction permit obligations, which give owners just a few years to get their stations on the air or face forfeiture of their permit and/or license.

Subscribe

Subscribe