A major battle between satellite owners, broadcasters, and the telecom industry has emerged over a proposal to repurpose a portion of C Band satellite spectrum for use by the wireless industry.

A major battle between satellite owners, broadcasters, and the telecom industry has emerged over a proposal to repurpose a portion of C Band satellite spectrum for use by the wireless industry.

Multiple proposals from the wireless and cable industry to raid C Band satellite frequencies for the use of future 5G wireless networks suggest carving up a band that has been used for decades to distribute radio and television programming.

Before the advent of Dish Networks and DirecTV, homeowners placed 6-12′ large rotatable satellite dishes in backyards across rural America to access more than a dozen C Band satellites delivering radio and television programming. Although most consumers have switched to much smaller fixed satellite dishes associated with Dish or DirecTV, broadcasters and cable companies have mostly kept their C Band dishes to reliably receive programming for rebroadcast.

Now the wireless industry is hoping to poach a significant amount of frequencies in the C Band allocation of 3.7-4.2 GHz to use for 5G wireless service. Competing plans vary on exactly how much of the satellite band would be carved out. One plan proposed by Charter Communications and some independent cable companies would take 370 megahertz from the 500 megahertz now used by C Band satellites and sell it off in at least one FCC-managed auction to the wireless industry. A more modest plan by an alliance of satellite owners would give up 200 megahertz of the band, allowing wireless companies to acquire 180 megahertz of spectrum. To reduce the potential of interference, both major plans offer to set aside 20 megahertz to be used as a “guard band” to separate satellite signals from 5G wireless transmissions.

Satellite dish outside of KTVB-TV in Boise, Ida. (Image courtesy: KTVB-TV)

Much like the FCC’s repack of the UHF TV dial, which is forcing many stations to relocate to a much smaller number of available UHF TV channels, most proposals call on the FCC to subsidize dislocated satellite broadcasters and users with some of the auction proceeds to help pay the costs to switch to fiber optic terrestrial distribution instead.

Broadcasters and satellite companies claim the cable industry proposal would leave U.S. satellite users drastically short of the minimum 300 megahertz of satellite spectrum required to provide radio and television stations with network programming. Many rural broadcasters have complained that the cable industry plan calling for a shift to fiber optic distribution ignores the fact that there is no fiber service available in many areas. Other objectors claim fiber outages are much more common than disruptions to satellite signals, putting viewers at risk of a much greater chance of programming disruptions.

With spectrum valued at more than $8 billion at stake, various industry groups are organized into coalitions and alliances to either support or fight the proposals. The Trump Administration has made it known it is putting a high priority on facilitating the development of 5G services to beat the Chinese wireless industry, which is already moving forward on a major deployment of next generation wireless networks. The FCC, with a 3-2 Republican majority, has signaled it is open to reallocating spectrum to wireless carriers for the rollout of 5G service. Unfortunately, much of this spectrum is already in use, setting up battles between incumbent users threatened to be displaced and the wireless industry, which sees big profits from acquiring and deploying more spectrum.

With serious money at stake, strains are emerging among some individual members of the different industry groups. Late last week, Paris-based Eutelsat Communications quit the largest satellite owner coalition, the C-Band Alliance. The move fractured unity among the world’s satellite owners, just as the FCC seems ready to move on a reallocation plan. Eutelsat will now lobby the FCC directly, reportedly because of concerns among shareholders that splitting off significant amounts of C Band spectrum is inevitable and could drastically reduce the value of Eutelsat’s share price. Eutelsat reportedly wants to independently participate in the FCC’s proceeding, potentially securing a larger amount of compensation from the FCC for the spectrum it will give up as part of a final reallocation plan.

Whatever compensation plan emerges will run into the billions of dollars. Satellite dishes will probably require new equipment to shield signals from interference, may require re-pointing to a different satellite (which could prove problematic for some equipment originally installed in the 1980s), and may even require the launch of additional satellites to provide more capacity in the newly slimmed C Band.

The FCC is expected to decide on the reallocation proposals this fall, with a signal repack likely to take between 18-36 months before the frequencies can be cleared for use by wireless operators.

Satellite owners, mobile carriers, and cable operators discuss reallocating part of the satellite C Band for use by 5G wireless networks. Sponsored by the industry-funded Technology Policy Institute. Sept. 3, 2019 (44:10)

Subscribe

Subscribe

Over the weekend, Scientology leader David Miscavige appeared at Flag Land Base, the Church of Scientology’s spiritual headquarters in Clearwater, Fla., to announce the imminent launch of the network. In Los Angeles, L. Ron Hubbard Way has been blocked off at the southern end for a celebration when the network goes live.

Over the weekend, Scientology leader David Miscavige appeared at Flag Land Base, the Church of Scientology’s spiritual headquarters in Clearwater, Fla., to announce the imminent launch of the network. In Los Angeles, L. Ron Hubbard Way has been blocked off at the southern end for a celebration when the network goes live. The average American broadband-equipped household now uses 190GB a month, more than 95% of which is online video, according to a new report from iGR Research.

The average American broadband-equipped household now uses 190GB a month, more than 95% of which is online video, according to a new report from iGR Research.

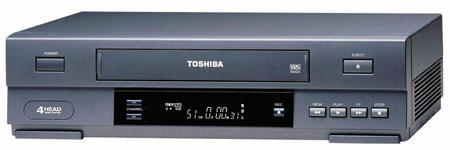

Consumers had a choice between two incompatible standards – the Sony Betamax, which promised superior video quality or JVC’s VHS format, a standard that allowed for longer recordings and was supported by just about every electronics manufacturer other than Sony. Some consumers owned both, but most settled for one or the other, and the VHS tape had a decisive advantage – extended recording time and near universal accessibility. It would eventually dominate in sales. More than 30 years later, recordings made on Betamax and VHS machines are still viewable, and turn up on video websites, often showcasing television as it used to look like in the 1970s and 1980s.

Consumers had a choice between two incompatible standards – the Sony Betamax, which promised superior video quality or JVC’s VHS format, a standard that allowed for longer recordings and was supported by just about every electronics manufacturer other than Sony. Some consumers owned both, but most settled for one or the other, and the VHS tape had a decisive advantage – extended recording time and near universal accessibility. It would eventually dominate in sales. More than 30 years later, recordings made on Betamax and VHS machines are still viewable, and turn up on video websites, often showcasing television as it used to look like in the 1970s and 1980s.