Comcast has been a part of life in Muskegon, Mich. for decades, thanks in part to an unusually long 25-year franchise agreement signed when President Reagan was serving his last year in office. In 1988, the Berlin Wall was still in place, Mikhail Gorbachev formally implemented glasnost and perestroika, Snapple appeared on store shelves nationwide, and compact discs finally outsold vinyl records for the first time.

Comcast has been a part of life in Muskegon, Mich. for decades, thanks in part to an unusually long 25-year franchise agreement signed when President Reagan was serving his last year in office. In 1988, the Berlin Wall was still in place, Mikhail Gorbachev formally implemented glasnost and perestroika, Snapple appeared on store shelves nationwide, and compact discs finally outsold vinyl records for the first time.

All good things must come to an end and Comcast’s contract to serve will finally expire Aug. 2. City officials want residents to understand that after two plus decades, it is appropriate to take some time to consider all the options. But a 2007 law has cut that time of reflection down to a month, and removed most of the powers Michigan communities used to have to select the best cable operator for their community. It’s a fact of life Comcast is well aware of, and it underlined that point by tossing a carelessly written, pro forma/fait accompli franchise renewal proposal into the mail that left Muskegon’s civic leaders cold. But if they fail to act fast, Comcast will win automatic approval of whatever it proposes to offer the 38,000 residents of the western Michigan city for years to come.

Statewide Video Franchising in Michigan

In December 2006, primarily at the behest of AT&T, the Michigan legislature passed a new statute that would create a uniform, statewide video franchise agreement template that providers could use to apply for or renew their franchises to operate. In theory, establishing a uniform, simplified franchise application would lead AT&T to quickly wire Michigan with U-verse, its competing cable/broadband/phone service, and bring dramatically lower prices for cable service and fewer complaints because of greater competition.

In December 2006, primarily at the behest of AT&T, the Michigan legislature passed a new statute that would create a uniform, statewide video franchise agreement template that providers could use to apply for or renew their franchises to operate. In theory, establishing a uniform, simplified franchise application would lead AT&T to quickly wire Michigan with U-verse, its competing cable/broadband/phone service, and bring dramatically lower prices for cable service and fewer complaints because of greater competition.

The Uniform Video Services Local Franchise Act was remarkably similar to those passed in more than a dozen other states — no mistake considering it was based largely on an AT&T-written draft distributed and promoted by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an AT&T-backed third-party group that encourages state legislatures to enact corporate-ghostwritten bills into law.

Under the new law, much of the power reserved by local officials to approve cable franchises and enforce good customer service was stripped away and handed to the state’s Public Service Commission. The deregulation measure tipped the balance of power in providers’ favor, making it possible to do business on their terms, not those sought by community leaders. Among the law’s provisions:

- Communities are still bound by the terms of their existing franchise agreements, but providers can break the legacy contracts for any reason, forcing a new agreement under the new statewide franchise law. If a provider wants out, they can abandon the community or transfer operations to a new provider with 15 days advance notice and no prior approval.

- A franchise renewal proposal will be automatically approved if a city does not reject it within 30 days.

- Communities cannot unreasonably restrict providers from access to public rights-of-way, an important consideration for AT&T’s U-verse, which requires the placement of large, sometimes noisy utility cabinets (a/k/a “lawn refrigerators”) to connect its fiber network with residential copper wiring.

- Communities are limited to collecting up to 5% of video revenue in franchise fees and up to 2% to support Public, Educational, and Government (PEG) channels. In the past, some communities asked cable operators to wire schools, libraries, and local government offices at no cost, and several negotiated other forms of support for PEG channels, which allow local citizens to view town board meetings and create and distribute locally produced programming. Today, those agreements are only possible on a voluntary basis, without any threat if a provider refuses, they will get their franchise request rejected.

- Providers are no longer obligated to honor agreements setting timetables to wire communities. Instead, they can handpick areas to be served, except in cases where racial or income discrimination can be proven.

Since the law was clearly designed to help new entrants like AT&T’s U-verse and Verizon FiOS, Michigan’s incumbent cable companies either demanded the same rights, remained neutral, or halfheartedly protested the proposed law suggesting it unfairly benefited new competitors. Cable companies, for example, would not benefit from laws throwing out buildout requirements because their networks are already largely complete.

But once signed into law, cable operators did begin asking cities to voluntarily adopt the new uniform statewide video franchise. Muskegon joined most other Michigan cities in declining the invitation.

AT&T did begin wiring Michigan for U-verse service, although there is no evidence it would not have done so had the Act never been signed into law. But that has not helped Muskegon, because the dominant phone company in the area is Frontier Communications. Frontier has so far shown no interest in building a competing cable TV service, so the only competition residents get are from two satellite companies.

City of Detroit v. State of Michigan and Comcast

Soon after the statewide franchise law was passed, Comcast notified the city of Detroit it could take the proposed renewal of its existing 1985 franchise agreement and go pound salt. The franchise agreement with the city expired in February 2007, just a month after the new law took effect. It was a new day, Comcast told city officials, and the company offered its own proposal for renewal — a 5% take-it-or-leave-it franchise fee and nothing else. Comcast even rejected the city’s counteroffer to include a 2% PEG fee, permitted under the new law.

Soon after the statewide franchise law was passed, Comcast notified the city of Detroit it could take the proposed renewal of its existing 1985 franchise agreement and go pound salt. The franchise agreement with the city expired in February 2007, just a month after the new law took effect. It was a new day, Comcast told city officials, and the company offered its own proposal for renewal — a 5% take-it-or-leave-it franchise fee and nothing else. Comcast even rejected the city’s counteroffer to include a 2% PEG fee, permitted under the new law.

Franchise negotiations went nowhere, but Comcast had nothing to fear. The city did not properly reject their franchise renewal offer so, as far as the company was concerned, it automatically won a franchise renewal.

The city sued both Comcast and the State of Michigan in the summer of 2010 alleging the statewide law violated the federal Cable Act, usurped local “home rule” authority, and that Comcast was illegally trespassing in the city without a franchise agreement. The Michigan Attorney General took Comcast’s side, defended the state law, and helped the cable company argue its case in court.

Comcast did not want the case heard and asked for its immediate dismissal, which was rejected.

In the summer of 2012, the judge split the decision between the city and Comcast. The judge found that Comcast had probably been operating illegally in Detroit since 2007 and owes the city damages. The judge also found parts of the state law troubling enough to invalidate. In particular, he emphasized cities do have a clear right to reject franchise proposals offered by cable operators and that in many cases those operators must adhere to their existing franchise agreements until they expire. Cities also have the right to protect and manage their rights-of-way, ending the perception cable and phone companies have the right to place hardware almost at-will in public areas.

Comcast wants to avoid paying Detroit damages for potentially operating illegally without a valid franchise.

The judge found nothing inherently faulty with the concept of statewide video franchising, nor did he rule that providers are required to serve everyone in a geographic area or that cities are allowed to enforce local customer service standards.

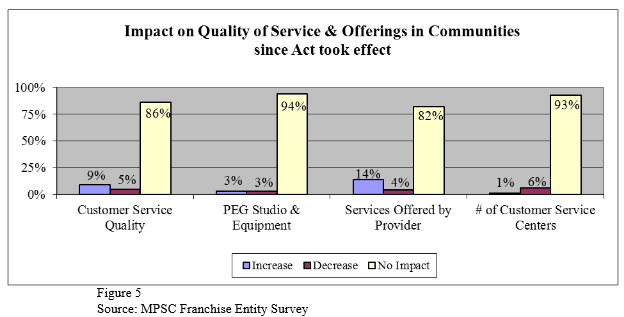

The impact of the statewide law, even after the judge’s ruling, still erodes local control. As pre-2007 franchise agreements expire, it is highly unlikely cable operators will continue to offer free service to municipal buildings, will not accept requirements to provide “universal service” or even language requiring wiring of every home that meets a “homes per mile” test. Some cable operators are even closing local customer service centers that used to be required in many franchise agreements.

Comcast did not appreciate the court ruling, sought to have it set aside, and failed. Now the Court of Appeals will likely weigh in on the case by the end of this year. Comcast is particularly concerned about the prospect of paying damages to the city of Detroit for illegally operating without a valid franchise. The judge hearing the case considered that a very real possibility and requested submissions from all parties about how much Comcast should pay the city.

Muskegon officials cited the judge’s rulings in the Detroit case in their letter rejecting Comcast’s proposed renewal agreement. The city wants to renegotiate certain terms regarding its PEG channels, still wants complimentary service to public buildings, and requests cable service be extended to the Hartshorn Marina.

Six Years Later, Cable Rates and Complaints Still Rising, the Competition is Fleeting, and Many Believe the Law Has Achieved Nothing

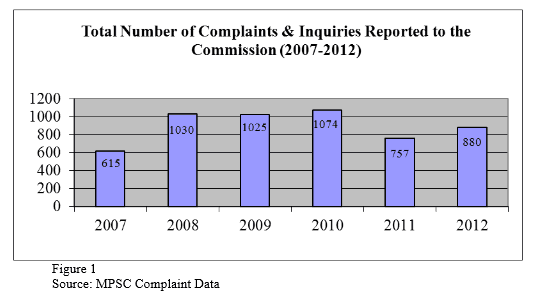

The Michigan Public Service Commission is tasked with reporting annually to the legislature and the public about the impact of the AT&T-sponsored law. The PSC’s broad conclusion is that the new law is working:

Increases in subscribers as well as the emergence of another video/cable provider are positive signs for the video services industry in the state of Michigan. Both franchise entities and providers have continued to report that video/cable competition is continuing to grow. Growth in competition has been observed each year since the Commission began issuing this report. In addition to the increase in competitive providers, companies continued to invest hundreds of millions of dollars into the Michigan video/cable market in 2012.

As the Act enters its seventh year of existence, signs of progress and competition continue to be evident. It appears that both franchise entities and providers perceive that providers are offering more services to customers. In addition, more areas throughout Michigan are beginning to have a choice of video/cable service providers.

But in the same report, the PSC admits the overwhelming consensus among those in individual communities is the law has made little to no difference in competition or pricing. For example, every provider has continued to raise their rates, particularly after promotional new customer packages expire. Much of the savings calculated in Michigan took introductory prices into account, such as when AT&T U-verse entered a market. After 1-2 years, those savings evaporate. AT&T has increased its pricing just as often as dominant cable providers Comcast and Charter.

The PSC touts that 15 new competitors have begun offering service in Michigan since the law was enacted. But besides AT&T’s U-verse., the majority of those new entrants are municipal telephone companies, small/family owned rural cable companies, or providers that specialize in serving only apartment complexes or condos. All but AT&T serve only tiny areas in Michigan and most have customers that number only in the hundreds to low-thousands.

Michigan’s New Competitors

- Ace Telephone Company of Michigan Inc.

- AT&T (U-verse)

- Bloomingdale Communications, Inc.

- Drenthe Telephone

- Martell Cable Service Inc.

- Mediagate Digital

- Michigan Cable Partners (MICOM Cable)

- Packerland Broadband

- Sister Lakes Cable TV

- Southwest Michigan Communications Inc.

- Spectrum Broadband

- Summit Digital

- Sunrise Communications LLC

- Vogtmann Engineering

- Waldron Communication Company

How many new Michigan customers has this competition netted since 2011? 2,116

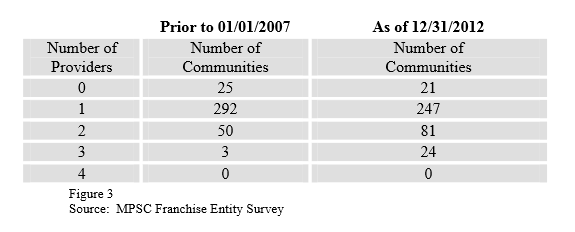

The overwhelming majority of Michigan communities still have just one cable operator and no competitor. AT&T U-verse accounts for almost all the communities reporting a second provider.

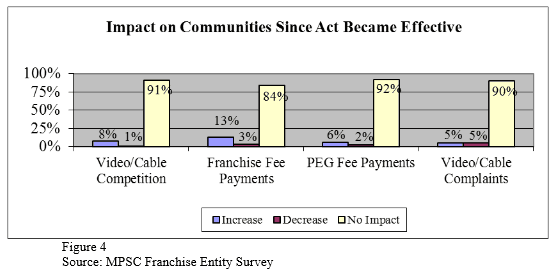

Complaints have also been higher every year the statewide franchise law has been in effect. In 2007, there were 615 formal complaints made to the PSC. Every year thereafter, the number of complaints exceed 2007 levels, ranging from 757 in 2011 to 1,074 in 2010. Comcast is by far the worst offender — 51 percent. AT&T and Charter had a smaller percentage of complaints, 15 and 14 percent respectively. The majority of complaints among all providers deal with billing issues.

Since the new law took effect, many communities have felt so disempowered, they stopped reporting local complaints to the PSC. But among those who have, the story is the same in states without statewide franchise laws:

- System updates not completed as promised. Large numbers (of residents) have gone to satellite;

- Upgrades needed to allow for better reception and channel selection;

- There are two providers in our area, yet little increase in competition;

- Cost to extend service to reach potential customers affects competition;

- Cable provider left when switching from analog to digital, stating not enough customers to afford the changeover. Now only satellite is available;

- No broadband/high-speed Internet service in many townships;

- No phone, cable service available;

- Michigan has totally failed bringing affordable Internet service to this community, and has prevented our township government from providing the needed services.

The perceived impact of the 2007 law isn’t so great either:

- Communities lost in-kind and other services from the incumbent provider;

- Cable rates continue to increase;

- Zero value added and has eroded local control of franchising;

- Customers have a choice now, but rates are still higher;

- Providers simply poach competitor’s customers as evidenced by flat franchise revenue; as one increases the other decreases;

- This statute has proven to accomplish literally nothing for municipalities and only serves to benefit providers;

- The Act did nothing to improve service.

Subscribe

Subscribe Residents of some cities north of Dallas are in the unique position of being able to choose between two phone companies and at least one cable operator for television, phone, and broadband service.

Residents of some cities north of Dallas are in the unique position of being able to choose between two phone companies and at least one cable operator for television, phone, and broadband service.

Susan Crawford’s new book, “Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age,” is on the receiving end of a lot of heat from industry lobbyists and those working for shadowy think tanks and “consumer groups.”

Susan Crawford’s new book, “Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age,” is on the receiving end of a lot of heat from industry lobbyists and those working for shadowy think tanks and “consumer groups.”