Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

That is the conclusion of researchers at Northeastern University, University of Massachusetts — Amherst and Stony Brook University, studying the results of more than 100,000 Wehe app users that have run 719,417 tests in 135 countries verifying net neutrality compliance, before and after the open internet rules were repealed in the U.S. earlier this year.

The raw data collected from the app is used as part of a validated, peer-reviewed method of determining which ISPs are throttling their customers’ connections and what services are being targeted.

Nearly Every Mobile Provider Is Throttling Your Speed, Even on “Unlimited” Plans

The researchers concluded that nearly every wireless provider is throttling at least one streaming video service, some reducing speeds the most for customers on budget priced plans while higher value customers are throttled less. No ISP consistently throttled all online video, setting up an unfair playing field for companies that benefit from not being throttled against those that are. Few customers noticed much difference in the performance of streaming video after the repeal of net neutrality in the U.S., largely because the wireless companies involved — AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, Sprint and others — were already quietly throttling video.

“Our data shows that all of the U.S. Cellular ISPs that throttled after June 11th were already throttling prior to this date,” the researchers wrote. “In short, it appears that U.S. Cellular ISPs were ignoring the [former FCC Chairman Thomas] Wheeler FCC rules pertaining to ‘no throttling’ while those rules were still in effect.”

Summary of Detected Throttling

For each ISP, the researchers included tests only where a user’s set of tests indicated differentiation (speed throttling of specific apps or services) for at least one app and did not detect differentiation for at least one other app. This helps to filter out many false positives. As a result, the number of tests in this table is substantially lower than the total number of tests Wehe users ran. The researchers sorted the Cellular ISPs based on the number of tests from users of each ISP. If they did not detect differentiation, researchers used the entry “Not detected.” The researchers claim that offers enough evidence that throttling is not happening. In some cases researchers do not have enough tests to confirm whether there is throttling, indicated by “No data.”

The table has two column groups for the results: before the new FCC rules took effect on June 11th, and after. If behavior changed from after June 11th, it is highlighted in bold.

| SP |

App |

Before Jun 11th |

After Jun 11th |

| Throttling rate (s) |

# tests |

# users* |

Throttling rate |

# tests |

# users* |

| Verizon (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.9 Mbps

4.0 Mbps |

10630 |

2859 |

1.9 Mbps

3.9 Mbps |

2441 |

702 |

|

Netflix |

1.9 Mbps

3.8 Mbps |

8540 |

2609 |

1.9 Mbps

3.9 Mbps |

2395 |

754 |

|

Amazon |

1.9 Mbps

3.9 Mbps |

5819 |

1949 |

1.9 Mbps

3.9 Mbps |

1267 |

440 |

| ATT (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.4 Mbps |

9142 |

2466 |

1.4 Mbps |

1708 |

571 |

|

Netflix |

1.4 Mbps |

4538 |

1540 |

1.5 Mbps |

1316 |

498 |

|

NBCSports |

1.5 Mbps |

3368 |

1326 |

1.5 Mbps |

589 |

238 |

| TMobile (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.4 Mbps |

3562 |

962 |

1.4 Mbps |

1185 |

373 |

|

Netflix |

1.4 Mbps |

1813 |

637 |

1.4 Mbps |

1074 |

387 |

|

Amazon |

1.4 Mbps |

1422 |

477 |

1.4 Mbps |

1422 |

318 |

|

NBCSports |

1.4 Mbps |

1588 |

626 |

1.4 Mbps |

579 |

231 |

| Sprint (cellular) |

Skype |

0.5 Mbps

1.4 Mbps |

533 |

210 |

1.4 Mbps |

132 |

46 |

|

Youtube |

2.1 Mbps |

224 |

56 |

2.0 Mbps |

39 |

12 |

|

Netflix |

1.9 Mbps

8.8 Mbps |

277 |

100 |

2.0 Mbps

8.9 Mbps |

40 |

15 |

|

Amazon |

2.1 Mbps |

116 |

45 |

2.1 Mbps |

24 |

8 |

| cricket (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.2 Mbps |

296 |

59 |

1.3 Mbps |

58 |

14 |

|

Amazon |

1.2 Mbps |

79 |

22 |

1.2 Mbps |

16 |

4 |

| MetroPCS (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.5 Mbps |

302 |

85 |

1.5 Mbps |

72 |

20 |

|

Amazon |

1.4 Mbps |

211 |

74 |

1.4 Mbps |

45 |

16 |

|

Netflix |

1.4 Mbps |

190 |

71 |

1.3 Mbps |

60 |

20 |

|

NBCSports |

1.5 Mbps |

152 |

67 |

1.5 Mbps |

39 |

16 |

| BoostMobile (cellular) |

Youtube |

2.0 Mbps |

80 |

12 |

2.1 Mbps |

10 |

1 |

|

Netflix |

1.9 Mbps |

52 |

8 |

2.0 Mbps |

14 |

4 |

|

Amazon |

2.1 Mbps |

55 |

8 |

2.1 Mbps |

6 |

1 |

|

Skype |

0.5 Mbps |

32 |

10 |

0.5 Mbps |

9 |

4 |

| TFW (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.2 Mbps

3.9 Mbps |

39 |

4 |

1.3 Mbps |

10 |

2 |

|

Amazon |

1.3 Mbps |

19 |

2 |

1.2 Mbps |

3 |

1 |

|

Netflix |

3.9 Mbps |

8 |

3 |

Not detected |

5 |

2 |

| ViaSatInc (WiFi) |

Youtube |

0.8 Mbps |

35 |

7 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

1.0 Mbps |

19 |

5 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Amazon |

0.9 Mbps |

15 |

5 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Spotify |

1.1 Mbps |

16 |

5 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Vimeo |

1.2 Mbps |

8 |

4 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

NBCSports |

1.2 Mbps |

7 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| HughesNetworkSystems (WiFi) |

Youtube |

0.4 Mbps |

24 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

0.7 Mbps |

16 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| CSpire (cellular) |

Youtube |

0.9 Mbps |

19 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| GCI (cellular) |

Youtube |

0.9 Mbps

2.2 Mbps |

18 |

4 |

2.0 Mbps |

4 |

1 |

|

Netflix |

2.0 Mbps |

13 |

4 |

2.1 Mbps |

4 |

1 |

|

NBCSports |

2.2 Mbps |

7 |

3 |

1.2 Mbps |

5 |

1 |

|

Amazon |

2.2 Mbps |

4 |

2 |

2.0 Mbps |

4 |

1 |

|

Vimeo |

0.9 Mbps |

3 |

0 |

2.2 Mbps |

4 |

1 |

| SIMPLEMOBILE (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.4 Mbps |

14 |

5 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Amazon |

1.5 Mbps |

9 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

NBCSports |

1.4 Mbps |

6 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

1.4 Mbps |

9 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| XfinityMobile (cellular) |

Youtube |

3.9 Mbps |

8 |

3 |

1.9 Mbps |

34 |

7 |

|

Netflix |

3.9 Mbps |

12 |

4 |

2.0 Mbps |

28 |

7 |

|

Amazon |

Not detected |

61 |

3 |

1.9 Mbps |

15 |

7 |

| NextlinkBroadband (WiFi) |

Youtube |

4.5 Mbps |

10 |

3 |

3.2 Mbps |

3 |

1 |

|

Vimeo |

5.1 Mbps |

6 |

1 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Amazon |

1.2 Mbps

4.1 Mbps |

5 |

1 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

4.1 Mbps |

4 |

1 |

Not detected |

1 |

1 |

| FamilyMobile (cellular) |

Youtube |

1.4 Mbps |

13 |

5 |

Not detected |

9 |

1 |

|

Amazon |

1.4 Mbps |

9 |

4 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

1.4 Mbps |

8 |

4 |

1.3 Mbps |

4 |

2 |

|

NBCSports |

1.4 Mbps |

6 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| Cellcom (cellular) |

Youtube |

3.9 Mbps |

9 |

4 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

3.2 Mbps |

5 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Amazon |

3.9 Mbps |

7 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

| iWireless (cellular) |

NBCSports |

2.8 Mbps |

8 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Youtube |

2.9 Mbps |

6 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Amazon |

2.8 Mbps |

7 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Spotify |

2.9 Mbps |

8 |

3 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Netflix |

2.8 Mbps |

6 |

2 |

No data |

No data |

No data |

Sprint’s Skype Throttle

The researchers found that video was not the only service impacted by speed throttles. Sprint (and its subsidiary, prepaid provider Boost), for example, is actively throttling Skype.

“This is interesting because Skype’s telephony service directly competes with the telephony service provided by Sprint,” the researchers wrote. But curiously, the throttle almost entirely impacts Android phone users, while iOS devices have less than a 4% chance of being speed throttled. But isolating the exact trigger for throttling remains elusive, the researchers claim.

“While we have strong evidence of Skype throttling from our users’ tests, we could not reproduce this throttling with a data plan that we purchased from Sprint earlier this year,” the researchers admit. “This is likely because it affects only certain subscription plans, but not the one that we purchased.”

When asked to comment, Sprint said: “Sprint does not single out Skype or any individual content provider in this way.” The test results indicate otherwise, suggest the researchers.

T-Mobile’s “Boosting” Throttle Can Mess Up Streaming Video

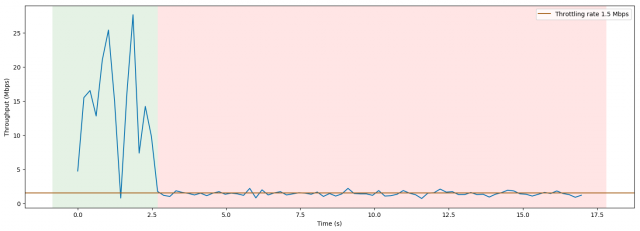

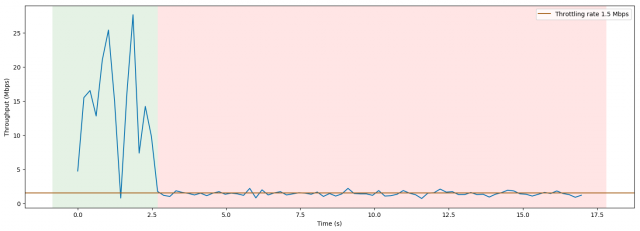

Some providers, like T-Mobile, attempt to sell their throttled speeds as pro-consumer. In return for reduced definition video, customers are free to watch more online content over their portable devices without it counting against a data cap. But T-Mobile’s video throttle is unique among providers as it initially allows a short burst of regular speed to buffer the first few seconds of a streamed video before quickly throttling video playback speed. Many video players do not expect to see initial robust speeds quickly and severely throttled. Consumers report video playback is often interrupted, sometimes several times, as the player gradually adapts to the low-speed, throttled connection. Consumers receive lower quality video as a consequence.

T-Mobile Plays Favorites

Through extensive testing, research found throttling begins after a certain number of bytes have been transferred, and it is not based strictly on time; below is a list of the detected byte limits for the “boosted” (i.e., unthrottled video streaming) period.

The impact of T-Mobile’s “boosting” speed throttle. Initial speeds of streaming video reach 25 Mbps before being throttled to a consistent 1.5 Mbps.

| App |

Boosting bytes |

| Netflix |

7 MB |

| NBCSports |

7 MB |

| Amazon Prime Video |

6 MB |

| YouTube |

Throttling, but no boosting |

| Vimeo |

No throttling or boosting |

More concerning to the researchers is their finding that video apps are treated differently by T-Mobile.

“T-Mobile throttles YouTube without giving it a boosting period, while T-Mobile does not throttle Vimeo at all,” the researchers report. “Such behavior highlights the risks of content-based filtering: there is fundamentally no way to treat all video services the same (because not all video services can be identified), and any additional content-specific policies — such as boosting — can lead to unfair advantages for some providers, and poor network performance for others.”

The team of researchers had just one conclusion after reviewing the available data.

“Net neutrality violations are rampant, and have been since we launched Wehe,” the researchers report. “Further, the implementation of such throttling practices creates an unlevel playing field for video streaming providers while also imposing engineering challenges related to efficiently handling a variety of throttling rates and other behavior like boosting. Last, we find that video streaming is not the only type of application affected, as there is evidence of Skype throttling in our data. Taken together, our findings indicate that the openness and fairness properties that led to the Internet’s success are at risk in the U.S.”

The team “strongly encourages” policymakers to rely on fact-based data to make informed decisions about internet regulations, implying that provider-supplied data about net neutrality policies may not reveal the full impact of speed throttles and other traffic favoritism that is common where net neutrality protections do not exist.

A dispute is emerging in New York between Sprint and T-Mobile and the Communications Workers of America (CWA) and pro-consumer group the Public Utility Law Project (PULP) over the wireless companies’ attempt to argue for their merger deal in a partly secretive filing not open to review by the public.

A dispute is emerging in New York between Sprint and T-Mobile and the Communications Workers of America (CWA) and pro-consumer group the Public Utility Law Project (PULP) over the wireless companies’ attempt to argue for their merger deal in a partly secretive filing not open to review by the public.

The merger of the two wireless companies requires state and federal approval. Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Texas, Utah, West Virginia and the District of Columbia have already essentially “rubber-stamped” approval of the merger deal with little comment. Pennsylvania regulators submitted a series of questions that the two companies answered earlier this week.

The merger of the two wireless companies requires state and federal approval. Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Texas, Utah, West Virginia and the District of Columbia have already essentially “rubber-stamped” approval of the merger deal with little comment. Pennsylvania regulators submitted a series of questions that the two companies answered earlier this week.

Subscribe

Subscribe Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

Nearly every wireless provider in the United States is intentionally slowing down your data service, detrimentally affecting smartphone apps and video streaming.

Altice USA’s Optimum (formerly Cablevision) and Suddenlink are getting upgraded technology as the two cable companies face increasing demands for speed and broadband usage around the country.

Altice USA’s Optimum (formerly Cablevision) and Suddenlink are getting upgraded technology as the two cable companies face increasing demands for speed and broadband usage around the country.

The upgrades will mean Suddenlink customers will be more likely to receive 1 Gbps speeds even during peak usage times.

The upgrades will mean Suddenlink customers will be more likely to receive 1 Gbps speeds even during peak usage times. “You’re giving it away… you are giving it all away!” — An unknown Wall Street analyst tossing and turning in the night.

“You’re giving it away… you are giving it all away!” — An unknown Wall Street analyst tossing and turning in the night. Even better, now with net neutrality in the ash heap of history, courtesy of the Republican-dominated FCC, providers can extract even more of your money by artificially messing with wireless traffic!

Even better, now with net neutrality in the ash heap of history, courtesy of the Republican-dominated FCC, providers can extract even more of your money by artificially messing with wireless traffic! The disappointment will eventually be all yours, dear readers, if Lowenstein’s recommendations are adopted — when “certain milestones” trigger “rate adjustment” letters some day in the future.

The disappointment will eventually be all yours, dear readers, if Lowenstein’s recommendations are adopted — when “certain milestones” trigger “rate adjustment” letters some day in the future. “Devastating.”

“Devastating.” The comments reflected consumer views that mergers in the telecom industry reduce choice and raise prices.

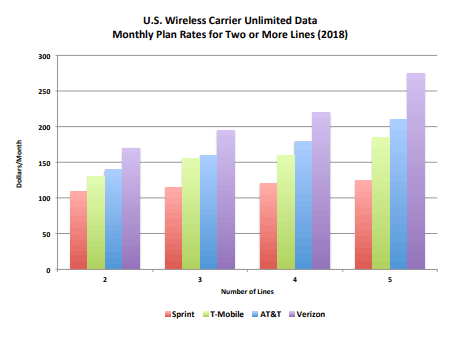

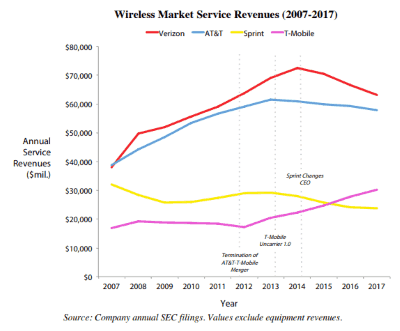

The comments reflected consumer views that mergers in the telecom industry reduce choice and raise prices. Rivals, especially AT&T and Verizon, have remained silent about the merger. That is not surprising, considering T-Mobile and Sprint have forced the two larger providers to match innovative service plans, bring back unlimited data, and reduce prices. A combined T-Mobile and Sprint would likely reduce competitive pressure and allow T-Mobile to comfortably charge nearly identical prices that AT&T and Verizon charge their customers.

Rivals, especially AT&T and Verizon, have remained silent about the merger. That is not surprising, considering T-Mobile and Sprint have forced the two larger providers to match innovative service plans, bring back unlimited data, and reduce prices. A combined T-Mobile and Sprint would likely reduce competitive pressure and allow T-Mobile to comfortably charge nearly identical prices that AT&T and Verizon charge their customers.