Karma’s very expensive $150 startup equipment package.

After customers spent $150 on a mobile Wi-Fi hotspot device promising unlimited LTE wireless Internet access for $50 a month, Karma – the company offering the service – has put a stop to its “Neverstop” plan four months after introducing it.

“Karma is a bitch,” complained one customer who spent $250 with Karma trying to find a replacement for Clear’s now discontinued WiMAX service for his rural home. “After spending hundreds for nothing, it should be obvious to everyone why Karma turned off the comment section on its website.”

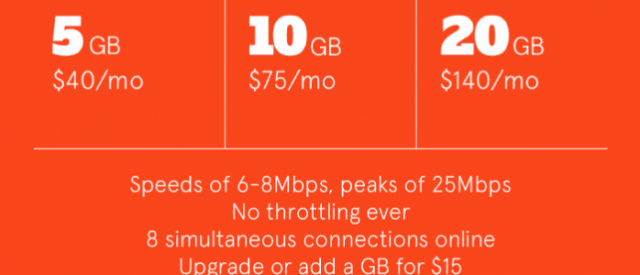

Neverstop customers have been through a rough ride during the brief life of the service, which started last November. Customers were promised unlimited 5Mbps service for $50 a month, after buying the $150 in required hardware. But not long after the plan was introduced, customers discovered their speeds were throttled to as low as 1.5Mbps to discourage customers from excessively using the service.

Insiders tell us the likely cause of the plan’s demise is Sprint, the wireless company Karma contracts with to offer the service. Sprint reseller contracts are closely guarded, but there is a clear track record of wireless companies taking action against resellers that place unexpected burdens on their networks. Millenicom, a similar provider that won customers largely through word-of-mouth, saw its unlimited offerings curtailed long before Karma announced its Neverstop plan, because wireless companies didn’t appreciate the fact some Millenicom customers relied entirely on the service for Internet access in the home.

Karma sold a plan that encouraged heavier data usage and then punished customers for using it.

Karma officials claim most of their customers never exceeded 15GB a month, but apparently enough did to get Sprint’s attention. Karma’s own internal research found that despite its insistence Neverstop was not a home broadband replacement, at least 60% of their customers used it exactly for that purpose. A handful of customers ran up hundreds of gigabytes of usage from online video, cloud storage/backup, and file trading. But a larger percentage used the service because they had no access to DSL or cable broadband, and used about as much data as the average household – an amount deemed by Sprint and/or Karma as “unsustainable.” Karma quickly moved to impose universal speed reductions on the service, dropping from 5Mbps to 1.5Mbps in an effort to curtail usage.

“Bait and switch,” complained Shannon Krakosky on Karma’s Facebook page. Many of the company’s earliest customers found the throttles arrived just as their 45-day return window for the expensive equipment expired, saddling them with a $150 paperweight. The company’s Black Friday offer inspired still more customers to sign up at a discount, only to find the equipment backordered, arriving at around the same time the traffic reduction speed throttles were announced.

Just one week before the speed reductions took effect, new customers were enticed with a year-end signup offer, further increasing traffic loads. Then customers received this:

[We] were surprised to learn how many of you are also using it heavily at home. We’ve seen lots of you binge watch Netflix in HD all day, back up your hard drives over the internet, and even connect your Xboxes through ingenious means. It’s a glimpse of how the internet should be, and we love it… but it’s putting a strain on the service and it’s not what the product is meant for today.

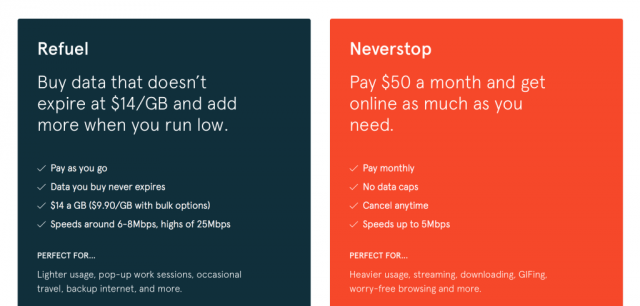

After spending $150 on hardware for $50 unlimited LTE service, less than four months later these are your new choices.

But usage should have never surprised Karma, considering the firm marketed Neverstop in November and December as the perfect answer for “heavier usage, streaming, downloading….”

Only after imposing a speed throttle — later increased to 2.5Mbps — came changes in how Neverstop marketed its service. In early January, Neverstop was now sold as the perfect solution for “daily usage, worry-free browsing, on-the-go work, travel, occasional streaming, and more.” Also gone was the marketing that promoted unlimited usage. The new message to customers: lay off.

Many customers were unhappy about the sudden changes and have filed false advertising complaints with the Better Business Bureau and several state attorneys general.

Karma continued to modify its Neverstop plan later in January, claiming to relent on speed throttling and moving to impose a 15GB usage cap on Neverstop instead. The company claimed the usage cap would allow it to restore 5Mbps service, but most customers complained their speeds remained slow. In effect, customers were being asked to continue paying $50 a month for a shadow of the service originally advertised.

As of late last week, Karma revisited customers again to announce the once unlimited wireless data experience of Neverstop was being stopped… permanently.

van Wel

Karma CEO Steven van Wel told Verge the company came to the realization that Neverstop was unsustainable after observing a month of customer usage following January’s adjustments. Even with the restrictive throttling, half of Neverstop customers reached the 15GB cap before the end of their billing cycle, and there was no way for them to easily continue high-speed service, whether by changing plans or paying overage fees. Just one month earlier van Wel told Verge only a few customers were likely to exceed their 15GB cap.

“You bait and switched us again,” came a chorus of complaints before Karma switched off public comments on all but its Facebook page.

“Poor business at best,” added Daniel Frisch. “Sell a customer one thing and then switch it to something completely different. You sold me an unlimited data device at a reasonable price and now you have gone from throttling that data to a high-priced limited data plan like everybody else.”

Karma’s latest plan is called Pulse and Neverstop customers will gradually find their existing Neverstop service transitioned to the new plan over the coming month, which will sell 5GB of service for $40 a month. Many complain there are better deals available elsewhere.

Stop the Cap! will continue to seek out options for rural or on-the-go customers who depend on wireless Internet access where DSL and cable broadband are not available. For now, we cannot recommend Karma because of the company’s unstable service plans and the high upfront cost of equipment.

Subscribe

Subscribe Sprint customers will once again have to endure service interruptions and disruptions and the possibility of degraded service after the cellular company quietly announced it was terminating leases with Crown Castle and American Tower — two of the largest owners of shared communications towers in the country, and relocating Sprint cell sites to government-owned property.

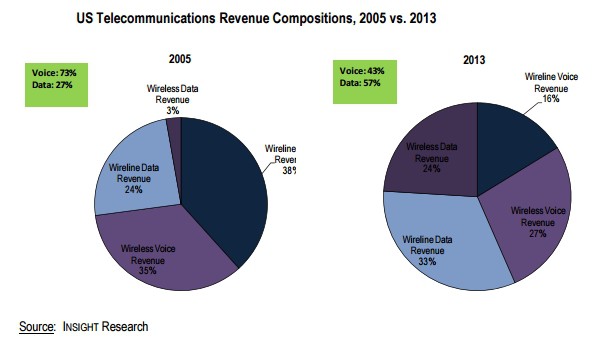

Sprint customers will once again have to endure service interruptions and disruptions and the possibility of degraded service after the cellular company quietly announced it was terminating leases with Crown Castle and American Tower — two of the largest owners of shared communications towers in the country, and relocating Sprint cell sites to government-owned property. The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time,

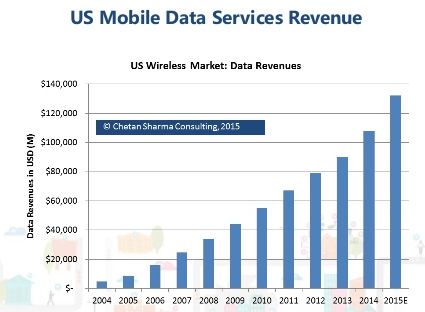

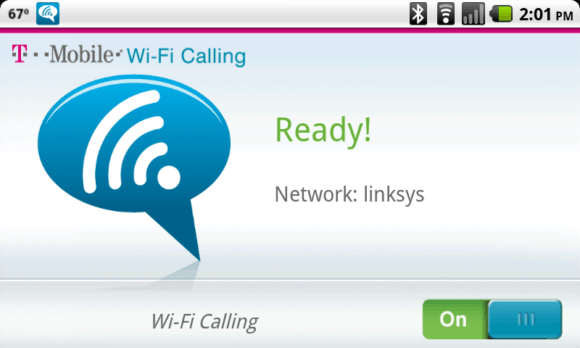

The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time,  Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging.

Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging. The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier.

The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier. Some even expect carriers to eventually

Some even expect carriers to eventually  Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint

Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint

Son has been relatively quiet since failing to inspire regulators to allow him to merge Sprint and T-Mobile into a single company to help both compete more effectively against giants AT&T and Verizon Wireless. After promising to invest vast sums to improve Sprint’s relatively poor performing network and coverage area, Son seemed to disappear and Sprint started losing more customers than it could add. Some have expressed frustration about Sprint’s seemingly endless promises a network turnaround was just around the corner, but never seemed to actually materialize. Many have since left for T-Mobile, which added 2.1 million new customers this year.

Son has been relatively quiet since failing to inspire regulators to allow him to merge Sprint and T-Mobile into a single company to help both compete more effectively against giants AT&T and Verizon Wireless. After promising to invest vast sums to improve Sprint’s relatively poor performing network and coverage area, Son seemed to disappear and Sprint started losing more customers than it could add. Some have expressed frustration about Sprint’s seemingly endless promises a network turnaround was just around the corner, but never seemed to actually materialize. Many have since left for T-Mobile, which added 2.1 million new customers this year.