Phillip “Every other 2008 spectrum bidder except U.S. Cellular has since sold its winnings to AT&T or Verizon Wireless or has never provided competitive service” Dampier

AT&T is unhappy with a proposal from a wireless competitor it originally tried to buy in 2011 that would offer smaller competitors a more realistic chance of winning favored 600MHz spectrum vacated by UHF television stations at a forthcoming FCC auction.

T-Mobile’s “Dynamic Market Rule” proposal would establish a cap on the amount of spectrum market leaders AT&T and Verizon Wireless, flush with financial resources for the auction, could win.

“Imposing modest constraints on excessive low-band spectrum aggregation will promote competition, increase consumer choice, encourage innovation, and accelerate broadband deployment,” T-Mobile offered in its proposal to the FCC.

Without some limits, wireless competitors Sprint and T-Mobile, among other smaller carriers, could find themselves outbid for the prime spectrum, well-suited for penetrating buildings and requiring a smaller network of cell towers to deliver blanket coverage.

In a public policy blog post today, AT&T argues T-Mobile is behind the times and its proposal is unfair and unworkable:

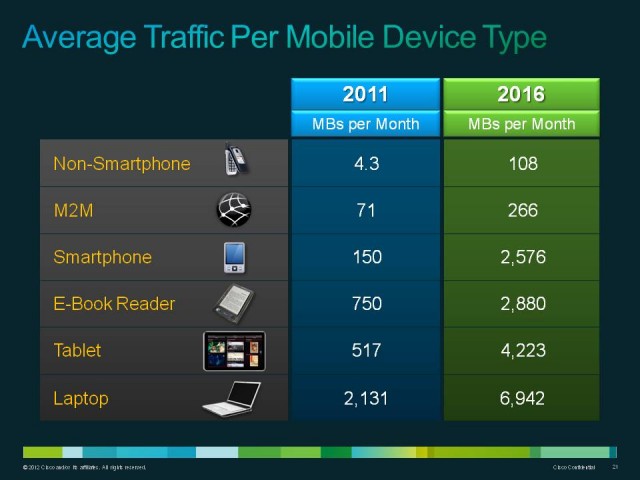

First, the purported advantage of low band spectrum – that it allows more coverage and better building penetration with fewer cell sites – has been overtaken by marketplace realities under which capacity not coverage drives network deployment. Carriers deploying low band and high band spectrum alike must squeeze as many cell sites as they can into their networks to meet exploding demand for data services. Second, to the extent this is less the case in rural areas, those areas are not spectrum-constrained and the lower cost of building out low band spectrum in such areas is offset by the higher cost of the spectrum itself.

[…] But this is not the only point that should concern policymakers. Such caps will also suppress auction revenues, potentially to the point of auction failure, ultimately reducing the amount of spectrum freed up for mobile broadband use and undermining the auction’s ability to meet critical statutory goals.

[…] Even if T-Mobile’s proposal did not result in complete auction failure, its proposed caps would suppress auction revenues, reducing the amount of spectrum freed up for mobile broadband use as well as funds generated for FirstNet and to pay down the national debt. That is because strict limits on participation by otherwise qualified bidders will make the auction less competitive and will yield less revenue. Indeed, if T-Mobile’s proposed spectrum cap was strictly enforced, Verizon estimates it would be barred from bidding in 7 of the top 10 markets. AT&T would face similar bidding limitations, as noted in our filing.

AT&T suggests the last major auction in 2008 attracted 214 qualified bidders and 101 bidders won licenses, including carriers of all sizes and new entrants.

But an analysis by Stop the Cap! shows the breakaway winners of the 2008 auction were none other than AT&T and Verizon Wireless, which paid a combined $16.3 billion of the total $19.592 billion raised. For that money, they acquired:

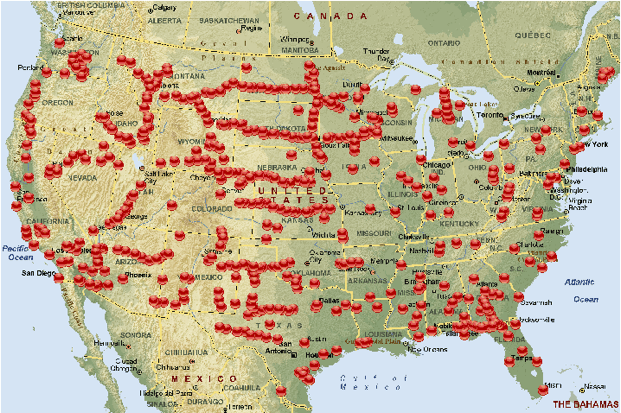

- Block A – Verizon Wireless and U.S. Cellular both bought 25 licenses each. In this block, Verizon targeted urban areas, while U.S. Cellular bought licenses primarily in the northern part of the U.S., where it provides regional cellular service. Cavalier Telephone and CenturyTel also bought 23 and 21 licenses, respectively. Cavalier Telephone is now wholly owned by Windstream, which does not provide cell service and was selling its 700MHz spectrum to none other than AT&T. So is CenturyLink (formerly CenturyTel).

- Block B – AT&T Mobility was the biggest buyer in the B block, with 227 licenses totaling $6.6 billion. U.S. Cellular and Verizon bought 127 and 77 licenses, respectively. AT&T Mobility and Verizon Wireless bought licenses around the country, while U.S. Cellular continued with its strategy to buy licenses in its home network northern regions.

- Block C – Of the 10 licenses in the C Block, Verizon Wireless bought the 7 that cover the contiguous 48 states (and Hawaii). Those seven licenses cost Verizon roughly $4.7 billion. Of the other three, Triad Communications — a wireless spectrum speculator — bought the two covering Alaska, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands through its Triad 700, LLC investor partnership, while Small Ventures USA, L.P. bought the one covering the Gulf of Mexico. Triad 700, LLC sold its spectrum last fall to AT&T while Small Ventures USA sold theirs to Verizon Wireless.

- Block E – EchoStar spent $711 million to buy 168 of the 176 available Block E licenses. This block, made up of unpaired spectrum, will likely be used to stream television shows. Qualcomm also bought 5 licenses. Neither company has used its spectrum to offer any services five years after the auction ended.

So much for improving the competitive landscape of wireless. Other than U.S. Cellular, which is rumored to be on AT&T and Verizon Wireless’ acquisitions wish list, every auction winner has either sold its spectrum to the wireless giants or has done nothing with it.

If “highest bidder wins”-rules apply at the forthcoming auction, expect more of the same.

AT&T and Verizon Wireless have significant financial resources to outbid Sprint, T-Mobile and smaller carriers and will likely win the bulk of the available spectrum whether they actually need it or not. Smaller victories may be won by smaller competitors, but only in rural areas and sections of the country disfavored by the largest two.

Subscribe

Subscribe AT&T announced late Friday it was acquiring Leap Wireless for almost $1.2 billion — a premium of 88 percent over Leap’s stock price.

AT&T announced late Friday it was acquiring Leap Wireless for almost $1.2 billion — a premium of 88 percent over Leap’s stock price. Many wireless industry observers believe AT&T is not interested in Leap/Cricket because of its business model. It is Leap’s spectrum holdings in large urban markets that makes it an attractive takeover target.

Many wireless industry observers believe AT&T is not interested in Leap/Cricket because of its business model. It is Leap’s spectrum holdings in large urban markets that makes it an attractive takeover target. Would you be surprised to learn a company with just a basic, outdated website replete with spelling and grammar errors holds at least 760 television station construction permits and licenses and just wrote a check for $46.5 million to buy 52 more stations from nine different owners, with plans to shut every last one of them down in the future?

Would you be surprised to learn a company with just a basic, outdated website replete with spelling and grammar errors holds at least 760 television station construction permits and licenses and just wrote a check for $46.5 million to buy 52 more stations from nine different owners, with plans to shut every last one of them down in the future? CTB Spectrum Services

CTB Spectrum Services

When Industry Canada announced it was planning to boost competition by setting aside certain spectrum for new competitors entering the wireless marketplace, the Conservative government promised Canadians they would see a new era of robust competition and lower prices as a result.

When Industry Canada announced it was planning to boost competition by setting aside certain spectrum for new competitors entering the wireless marketplace, the Conservative government promised Canadians they would see a new era of robust competition and lower prices as a result.